Did Vietnam peace protests stop Nixon using nuclear weapons?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

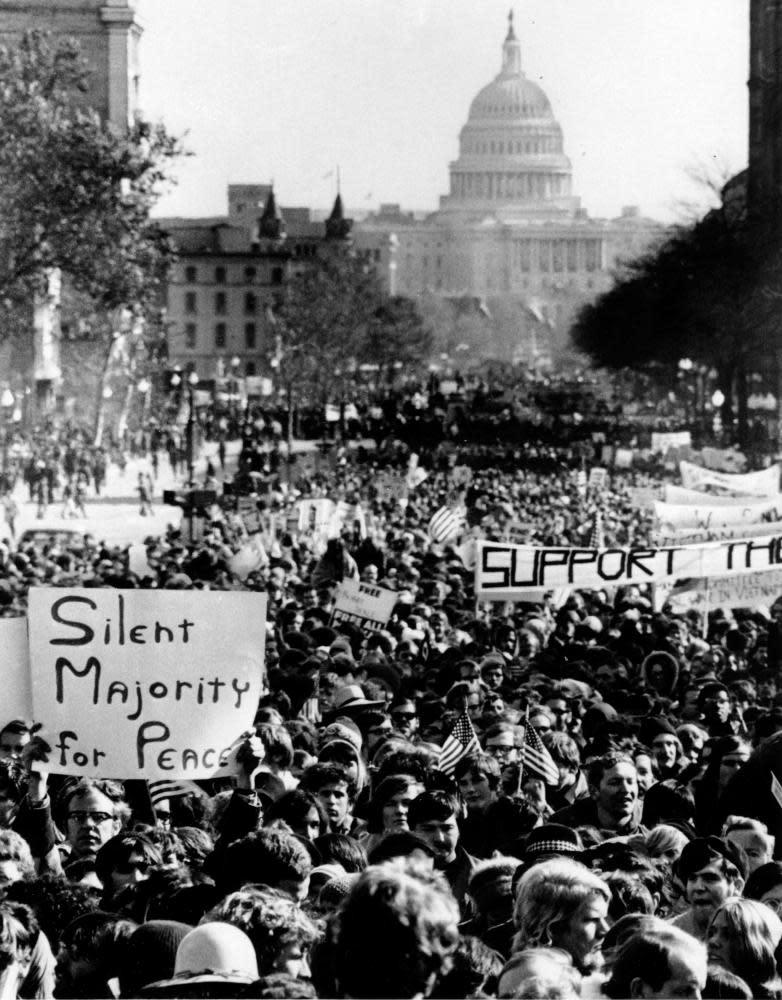

A new documentary about demonstrations against the Vietnam war in late 1969 argues that the hundreds of thousands who filled the streets in Washington and almost every major US city convinced Richard Nixon to abandon a plan to sharply escalate the war, including the possible use of tactical nuclear weapons.

Related: ‘We may have lost the south’: what LBJ really said about Democrats in 1964

The Movement and The “Madman” will air on PBS on Tuesday. Produced and directed by the veteran documentarian Stephen Talbot, it evokes a peak moment of 1960s activism – and the “absolute disconnection” between what Nixon and his national security adviser, Henry Kissinger, were “deciding to do and the human costs of it, whether it’s to our own soldiers or [Vietnamese] civilians”.

Those costs “had absolutely no part of their thinking” said the historian Carolyn Eisenberg. “They don’t care.”

Talbot’s sure eye for searing images is matched by a perfect ear for songs. His soundtrack includes anti-establishment hymns by Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, Jimi Hendrix and Judy Collins, plus the essential anti-war anthem, I-Feel-Like-I’m Fixin’-to-Die Rag, which became world famous after Country Joe McDonald performed it at Woodstock in summer 1969.

The one thing the documentary does not do is provide any convincing evidence that the demonstrations prevented the use of nuclear weapons.

“It is a serious look at how one major demonstration was organized,” said Thomas Powers, author of The War at Home, a history of the anti-war movement; The Man Who Kept the Secrets, a widely admired biography of the former CIA director Richard Helms; and seven other books.

But as far as the idea that “a real danger of the use of atomic weapons was prevented [by the Vietnam Moratorium] – I think that’s just plain wrong”, Powers told the Guardian.

Talbot responded that declassified documents about Operation Duck Hook, which laid out options for Nixon, included the possible use of nuclear weapons as well as the mining of Haiphong harbor and the bombing of dykes that would have caused massive civilian casualties.

As to whether Nixon seriously considered the nuclear option, Talbot said: “I literally don’t know and I don’t think anyone could say for sure. But it was on the table.”

The “madman” of Talbot’s film is Nixon. One thing that is not in dispute is that the president worked hard to convince the North Vietnamese and the Russians he was crazy enough to do anything, including pulling the nuclear trigger, if Hanoi refused his demands to withdraw from the south.

As Stephen Bull, a former Nixon aide, explains in the film, his boss wanted the Russians to “think that he was a madman. However, my personal observation was, it was a bluff. He was never going to use nuclear weapons, but he wanted the threat to be out there to force them to the table.”

Powers likened Nixon’s threats to use nuclear bombs to Vladimir Putin’s current threats to use such weapons against Ukraine – which Powers doesn’t think are serious either. Talbot agreed that was a possibility.

In his memoirs, Nixon wrote: “Although publicly I continued to ignore the raging anti-war controversy, I had to face the fact that it had probably destroyed the credibility of my ultimatum to Hanoi.”

The other thing the demonstrations almost certainly accomplished was the passage of a law, signed by Nixon in November 1969, which created a draft lottery.

On 1 December 1969, every draft-eligible young man born between 1944 and 1950 was assigned a number based on his birth date, from one to 365. The following year, the Pentagon announced that no one with a number higher than 195 would be drafted. A year later that number dropped to 125, then to 95 the year after that.

Since everyone in the streets in 1969 was demonstrating in no small part because of an acute desire to avoid dying in what they considered a pointless conflict, the lottery had an immediate effect in reducing the number who felt a sense of urgency about the war.

If you had a high enough number, your life was no longer in danger. After the very first lottery, more than a third of those previously subject to the draft no longer felt any imminent jeopardy. So there was less self-interest to propel the anti-war protests.

Talbot agreed that the lottery was a direct result of the anti-war demonstrations, and said he included it in an earlier, longer version of his film – but it did not make the final cut. In fall 1969, he was a senior in college. He went to DC to make his first film, March on Washington, which became his senior thesis when he attended Wesleyan University.

Related: Victor Navasky, the New York Times and a key moment in gay history

“I used clips from my first student film for this documentary,” he told the Guardian.

The truth is, while the Vietnam demonstrations did reduce the dangers of the draft, there is almost no evidence they shortened the war. When Nixon took office, 31,000 Americans had been killed in Vietnam, plus hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese. By the time the last American combat troops left in March 1973, two months after the draft was abolished, 58,220 US soldiers had died – plus as many as 2 million Vietnamese civilians and 1.3 million Vietnamese soldiers.

The Movement and The ‘Madman’ airs on PBS at 9pm ET on Tuesday and will stream on pbs.org

Charles Kaiser’s books include 1968: Music, Politics, Chaos, Counterculture, and the Shaping of a Generation