He didn't just usher in Black Studies at UD. James Newton leaves an artistic legacy

It was exhausting.

Heading to classes, grabbing meals in dining halls, walking across campus in the late 1980s, early '90s — Tony Allen remembers he could go a week, at times, without seeing another face like his. On bad days, it was too easy to question whether you belonged at all. Professors, students, staff: fellow Black Blue Hens felt scarce.

Especially if you didn't know where to look.

But one man allowed University of Delaware's Black scholars to thrive, rather than survive. He was "chicken soup for the beleaguered soul" who felt isolated on a majority-white campus, as well as the tough-love reminding them to excel there. He's also credited with ushering in the first successful Black American Studies program, over two decades after the university was forced by court decision to even allow such student admission.

James Newton, a South Jersey native who would become the first Black graduate with a master of fine arts from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and later a doctorate in education, came to UD in 1972. Delaware's largest university was never the same.

"It was tough at the University of Delaware," Allen said, remembering days far before leading Delaware State University today. "And I'm telling you, I couldn't go into percentages, but there are very few people, Black students under his tenure, that would have gotten through to the University of Delaware so successfully without him."

And somehow, Newton captured that journey in more ways than decades of student mentorship, writings, college courses and family stories. When he wasn't supporting students behind the scenes, lifting young creatives on several boards and projects — he was creating his own art.

This winter, Delaware Museum of Art and collaborating partners hope to highlight just that. DelArt will host an exhibition dedicated exclusively to Newton's work. Offering a new glimpse into his mind for some, the collection spans mediums, spans his early career — and pulls from his private collection.

Not all his students have seen much of it.

"Every time I think of folks who hold different experiences in our head, interfacing with Dr. Newton, I think about how multi-layered he was," Allen said. "He could influence you in Black American history. He could influence you in Black art. He could influence you in civil rights, and he can influence you with his own work."

The state lost a giant in May 2022, even if many say he was more comfortable out of the spotlight. He was presented with an honorary doctor of humane letters degree from UD after his death, alongside other events in the community. Today, the now-department of Africana studies gives the James E. Newton Student Award to a scholar each year who exhibits "qualities of excellence" in community service and achievement embodied by its namesake.

"You could find Dr. Newton in so many tentacles of what it means to be Black in Delaware, Black in America," Allen continued.

And starting Jan. 27, his work will be under the spotlight.

The real art of it all

The best part of Margaret Winslow's job is also the worst.

"It's taking, you know, hundreds of works of art and making those decisions," said DelArt's chief curator with a smile. "It's a great place to be in though."

Winslow, UD's Amanda Zehnder and their teams got to spend "invaluable" time with Newton's art and private collections thanks in large part to his wife, Lawanda, and surviving family. UD's Mechanical Hall and Morris Library will also host more works of Newton, including his writings, during the same period.

Even if students, former colleagues or community members haven't immersed themselves in Newton's fine art endeavors, Winslow is confident they'll feel a familiar spirit in the exhibition. She finds it in his style alone.

"Evolving, expanding, multilayer, multidimensional," she listed.

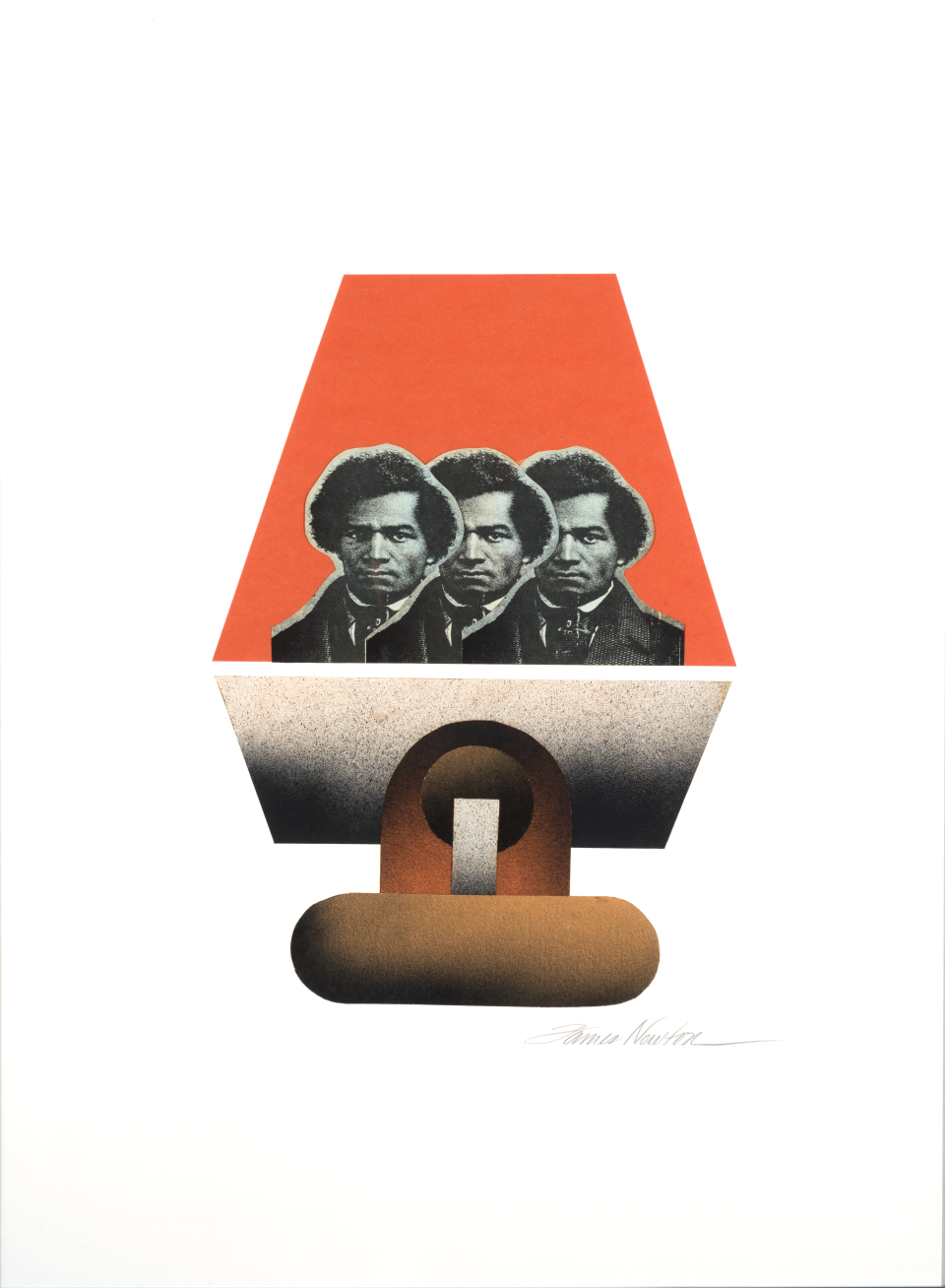

"Dr. Newton really pushed experimentation. He pushed working through abstraction, incorporating figuration, developing his own visual vocabulary, working across different media. He worked in printmaking, worked in painting, worked in assemblage — he is continuing to evolve to respond to all of these different histories, critical social moments, in his own individual and unique voice."

The result, she believes, is a journey patrons can follow through his pieces. Whether it's an "Homage to Frederick Douglass" collagraph or "The Love Machine" abstract acrylic on canvas, works in this collection pull across days studying in the '60s and days after his UD retirement in 2005.

"It really exudes that energy of a constant, constant move forward," Winslow said.

His former institution doesn't want that energy going anywhere.

Look back: The Vision of Percy Ricks is celebrated at Delaware Art Museum

'The gravity is real'

Kimberly Blockett never met James Newton. Most of her students probably haven't either.

Regardless, his impact couldn't be lost on her.

"The gravity is real," said the professor and today's chair of Africana studies. She took on her role hoping to build on a mission long engraved in the department. Newton aimed to see both academic and service work emphasized, she said, and such an ethos "still stands decades later."

Newton's style of supporting Black students, offering safe and celebrated spaces on a challenging PWI campus, also hasn't gone anywhere. Blockett still hears stories.

"At some point, they wondered if they were supposed to be there," she said of former Black Blue Hens. "There was some barrier or some issue that made them feel, you know: Maybe this isn't the place for me to be? Or maybe I can't continue? Or maybe I can't finish? Whatever those doubts are — the community that Dr. Newton established for Black students to be together, to have mentorship, really made it possible for students to not only finish, but to thrive."

Blockett only wants that support to grow. And while many of Newton's former students and colleagues will attend his exhibit, she believes an important message can be found for new students, too.

Opinion: Dr. James E. Newton: Ubuntu, Good Brother, Ubuntu!

"For them to see how much passion he put into his own artistic expression," she said. "His art expresses what he was making of the world at any given moment. It shows him as a whole human being. He wasn't just a teacher; he wasn't just a worker; he wasn't just an activist. He was a creative — and really brilliant at it."

More community events are expected in connection with DelArt's exhibition, "The Artistic Legacy of James E. Newton: Poetic Roots," and the cost to view is included in admission. That's $14 for adults. Just five days ahead of the two-year anniversary of Newton's death, the collection is slated to close on May 19.

Got a story? Contact Kelly Powers at kepowers@gannett.com or (231) 622-2191, and follow her on Twitter @kpowers01.

This article originally appeared on Delaware News Journal: He didn't just lift Black study at UD. James Newton left legacy in art