'We didn't let this place die': St. John Colony, Texas, endures for 150 years of grace

ST. JOHN COLONY, TEXAS — "Take a right at the cemetery, then head about 5 miles — country miles, you know — till you see the church spires," the helpful man in the tiny community of Dale said to the lost reporter. "That's when you are in St. John Colony."

Spread out lightly around FM 672 southeast of Austin, St. John Colony, founded in 1872 by 14 families fleeing racist violence in Bastrop County, is not an easy place to find, even with GPS.

Once there, however, one cannot miss the grace of the place.

Not just the clustered steeples, or the oak-fringed fields, but the sense of history, of trial and triumph, of periodic racist violence but, most of the time, abiding rural peace.

While many, if not most of Texas' freedom colonies — founded by independent, land-owning African Americans after emancipation — have faded away, St. John endures.

"God has a hand in it," said Vessie Davis Tutt, 96, the clerk at St. John Regular Baptist Church, and before that, clerk at Mt. Calvary Missionary Baptist Church in Austin, which her father founded. "He keeps us together to serve each other and to serve him.

"We didn't let this place die. Because what the 14 families — and of course my grandfather, Andrew Davis, was one of those — did was too good to let go. As my father would say: 'Keep your hands on the plough.'"

More: Austin Community College kicks off Juneteenth celebration

The grace can be felt on the grassy Juneteenth field behind St. John Regular Baptist Church, where Juneteenth has been celebrated for 150 years. The celebration is coordinated by the nonprofit organization St. John Juneteenth Body; Marshall Hill is its president.

Three Baptist churches still rise on the edges of the Juneteenth field. A fourth, St. John's Zion Union Baptist Church, is not far from the St. John Colony Cemetery, but is sadly falling apart.

The remoteness of this spot on rolling prairie land is not an accident.

Not far from Lytton, Haggai and Plum creeks, the land is well-watered. But just as importantly, in the 1870s, it lay far from the white power structures in the county seats of Bastrop and Lockhart, and the periodic threats that St. John's residents faced.

The previous location of the 14 families, Hogeye near Elgin in Bastrop County, proved too chaotic and dangerous during the later days of Reconstruction.

"Before emancipation, the families came from different locations in Texas but not too far from Hogeye," said Louis Simms, the unofficial genealogist of the St. John community. "Some members of the Hill family, for instance, came to Hogeye from the Hill plantation, Ancient Oaks, in Hill's Prairie. The Davis family was enslaved on the Ed Burleson land grant that stretched from Austin east and south."

Some accounts of the flight to St. John Colony focus on Webberville in Travis County as a possible jumping-off point for some of the migrants. Simms believes that small town served instead as a way station on the route between Hogeye and St. John.

The Bastrop County community of Hogeye, sometimes elided with Perryville, has been associated with several creation stories.

"It was on the stage line," Simms said. "Story goes, there was one bar with a piano and the player only knew one tune, 'Hogeye' (a sea shanty)."

Their success as independent Black landowners and operators of businesses in the Hogeye area caught the eye of white terrorists. Federal troops, who had protected freedmen during the early years of Reconstruction, withdrew, and a subsequent escalation of violence brought in state troops a short time later.

In his harrowing book, "Bastrop County During Reconstruction," Kenneth Kesselus describes the systematic terrorizing of Black residents, who made up 40% of the county's population, and any native-born white person or, especially, German American allies, who helped them. Teachers of Black children were particular targets.

"The state of affairs became worse daily, with additional murders and abuse of African Americans," Kesselus writes. "People of both races became alarmed, and no one considered it safe to travel unaccompanied."

In 1871, a rail line from Houston aimed at Austin passed through the area and predicated a local boom, which only intensified tensions that had boiled over since Black Texans learned of their freedom in 1865, two years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

"Whites in Texas were incensed by what had transpired, so much so that they reacted violently to Blacks' displays of joy at emancipation," writes Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Annette Gordon Reed in her 2021 book, "On Juneteenth." "In one town, dozens of newly freed enslaved people were whipped for celebrating. All over the South, but in Texas particularly, whites unleashed a torrent of violence against freed men and women — and sometimes whites who supported them — that lasted for years."

More: 'History that belongs to all Americans'; Leander to host first Juneteenth festival Saturday

St. John Colony is named in honor of the Rev. John Henry Winn Sr., a Baptist circuit rider who, like the biblical Moses, led his people to a promised land. In this case, that was 2,200 acres purchased in Caldwell County just across the Bastrop County line.

Originally, it was named Winn's Colony. When the first St. John Regular Baptist Church rose, the community changed its name.

Winn's name is also associated with the founding of the St. John Regular Baptist Association, a group of mostly Central Texas churches that once operated an orphanage and school on the land where Austin Community College Highland Campus now stands. The group held gigantic encampments each year on that land, featuring sermons, performances, contests and workshops.

St. John — alternately St. John's — is also the name of a thoroughfare and a neighborhood where the still-active association's tabernacle stands in Northeast Austin.

'Education and church'

Simms' genealogical work began, but did not end, with graves.

The oldest ancestor with a marked grave in the St. John Colony Cemetery is Jane Roland (1809-1915). Her crowned obelisk is adorned with the names of her children, but also the numbers of her grandchildren, great-grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren. When she died at age 106, her total descendants stood at 256.

There might be even older folks interred there. Not all graves are marked, including a raised area near the cemetery gates that serves as the final resting places for some of Louis Simms' ancestors, according to his late father.

"The graveyard is almost full," Simms says. "It's only an acre, and it has always been free, so sometimes people just stopped by the side of the road without telling anyone and buried their loved ones here."

It is telling that Azie Taylor Morton, the community's most famous one-time resident, chose to be buried here. As treasurer of the United States under President Jimmy Carter, she easily qualified to be interred with honors at the Texas State Cemetery. Her gravestone is instead here near the entrance gates; visitors leave coins in a small round tin that lays beneath her crisply rendered name.

More: With African American Cultural Center, the legacy of freedom colonies perseveres in Bastrop

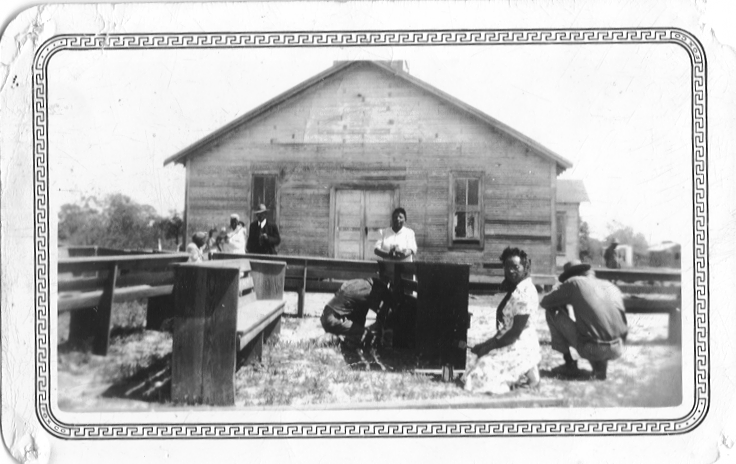

The original 1870s colony church is gone. Another former building for St. John Regular Baptist Church, a wooden structure built in the 1950s, is now called the Joe Ivan Roland Community Center. It sits next to a handsome 21st century church, where the Rev. H.L. Carter serves as pastor.

Just a few yards away is the St. John Landmark Baptist Church, formed by a breakaway group.

"They believed in two things: education and church," said Janet "Telee" Roland Weiss, who grew up in the community and is writing a history of it. "The children were raised right here. If you did something wrong, not only would your mother punish you, so would your aunt and your cousin. They'd take switch from a mesquite tree and — watch out!"

Among the community's most influential members was the Rev. S.L. Davis, who wrote one of the first histories of the colony. Davis went on to lead two congregations in Austin, including Mt. Calvary Missionary Baptist Church, which he founded and helped build.

He became a longtime leader among Austin ministers, known as "East Austin's Pastor."

The 14 families did not escape racist hatred and violence altogether when they settled in St. John Colony.

In 1917, as tensions rose with the second coming of the Ku Klux Klan, one violent incident in and near St. John ended with two unconfirmed murders, several beatings and the flight of one branch of the Hill family to Oklahoma in hopes of escaping further violence.

In his book, "From a Prince to a Slave," the Rev. Webster Gregg recounts a Hill family story about a fight that broke out in a nearby settlement among white and Black attendees at a traveling circus. White men chased the Hills back to St. John Colony, where the Hills burned down their house to cover their tracks in their escape to the north.

The chilling details of the night were passed on to Gregg by the Hills' Oklahoma descendants but remained a secret for decades to protect the family's safety.

A few days before Juneteenth 2020, a large noose was found hanging from the rafters at Zion Union Baptist Church. According to a spokesman for the Caldwell County sheriff's office, no suspect was ever found.

The Rev. Lee Otis Carter served as pastor at Zion Church from 1992 until the church building closed some 10 years ago. He still lives in St. John Colony and sometimes holds services in the church's standing cafeteria.

“It hurts deeply. I’ve got to battle that grief seeing them destroy God’s house like that," the Rev. Carter told a San Antonio TV news reporter in June 2020. “That church has been a cornerstone."

'A time comes to everybody'

The St. John Colony's two-room country school, built in 1903, was turned into a historical museum that opened in 2021.

"A folding partition divided the room," Simms said. "It was grades 1 through 5 on one side, 6 through 8 on the others. But it also served as a kindergarten and a babysitting center. So I was here even before I started school."

While he respected his teachers, Simms regrets that he didn't learn more Black history in the school.

"As kids, we didn't think about segregation. That's just the way it was," Simms said. "They didn't teach us the negative aspects of segregation, and we never thought to hate white people. We took being a Christian seriously. We remain strong advocates for God."

Like many people, Simms did not fully appreciate his family background and the achievements of his ancestors until he had reached adulthood.

"I didn't care about the programs at Juneteenth when I was young," Simms said. "I didn't pay attention. Then, when I was about 30, an elder recruited me to run those programs, saying, 'This is your time. A time comes to everybody.'

"You can't force people to care about their history. It's a choice. All we can do is put it out there."

Weiss added, "We don't want these stories to go to the grave with us."

Michael Barnes writes about the people, places, culture and history of Austin and Texas. He can be reached at mbarnes@statesman.com.

The 14 founding families of St. John Colony

Each founding family is identified by its patriarch or matriarch. Jane Roland, who did not travel with the first wagons from Hogeye, is often included on founder lists. When she died in 1915, she already had 256 descendants.

Rev. John Henry Winn Sr. (leader)

Rev. Calvin Allen Sr.

George Arnold

Andrew Davis

William "Billy" Carter

Berry D. Davis

Martin Frank

Jeff Franklin

Josiah Hill

Lamar Hill

Moses Hill

Simon Hill

Monroe Johnson

George Mackey

More on Juneteenth at St. John

A USA Today Network special section on Juneteenth includes another story by Michael Barnes on the 150th Juneteenth celebration at St. John Colony, Texas. Find it at statesman.com.

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: Juneteenth: St. John Colony founded 150 years ago to escape violence