‘They was different from what we were.’ Why a KY couple was charged with sedition

On Aug. 11, 1967, a posse of men from the Pike County sheriff’s office raided the rented home of Alan and Margaret McSurely, anti-poverty workers employed by a civil rights organization called the Southern Conference Educational Fund.

The McSurelys were jailed for a week and charged with the state crime of sedition, suspected of “plotting the violent overthrow of Pike County.” The evidence against them — trucked off by Sheriff Perry Justice — was their “suspicious” personal library of hundreds of books, magazines and private letters.

Their books covered history, biography, religion, philosophy, anti-war treatises about U.S. involvement in Vietnam, and such novels as Leo Tolstoy’s classic “War and Peace” and Joseph Heller’s satirical “Catch 22.” They had “The Communist Manifesto” by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and the Bible.

“A communistic library out of this world,” was how Pike Commonwealth’s Attorney Thomas Ratliff described it to reporters.

Apart from being the felony prosecutor in Pikeville, Ratliff was a wealthy coal operator and that year’s Republican nominee for lieutenant governor.

“I want to warn McSurely that if he calls on Russian tanks to help him conquer Pike County, I intend to appeal to Mayor (Richard) Daley of Chicago and (former Alabama) Gov. George Wallace for help in defending Pike County,” Ratliff continued, invoking the names of two politicians known for their strong-arm tactics.

A local friend of the McSurelys, Edith Easterling, recalled in a 1987 oral history interview: “It wasn’t just their books and their letters and the pictures off their walls. (The sheriff’s posse) took everything in the house. They had to take their toothbrushes and their toothpaste so they could fill up the truck and say, ‘Look at all this stuff we found!’”

The McSurelys denied plotting to overthrow anything or having communications with Russia.

Inside the Pike County jail, other inmates asked what charge he and his wife faced, Alan McSurely recalled in a September interview with the Herald-Leader. Now 87 years old, McSurely is a retired civil rights lawyer living in North Carolina.

“Sedition,” he told them.

The inmates asked what that meant.

“Plotting the violent overthrow of the government,” he explained.

“After a pause, they all go, ‘Right on, brother!’ Given the crowd this was, they were impressed,” McSurely said, laughing.

A home is bombed

A federal court swiftly dismissed Ratliff’s prosecution, finding Kentucky’s sedition law to be unconstitutional. The court ruled that sedition can only be committed against the United States, not against Pike County or the state of Kentucky.

(After a long legal battle, in 1983, the McSurelys would be awarded $1.2 million in damages from Ratliff for violating their civil rights.)

But the legislature’s Kentucky Un-American Activities Committee — often known by the acronym KUAC — was not satisfied with the dismissal.

KUAC investigated the McSurelys a year later, devoting part of its Pikeville hearings in October and December 1968 to criticism of the young couple and their liberal politics.

The committee scrutinized several groups, like the McSurelys’, that came to Appalachia as part of the War on Poverty in the 1960s to teach children, organize the poor in remote rural communities and fight strip-mining. The accompanying newspaper headlines warned about the specter of communism in the mountains.

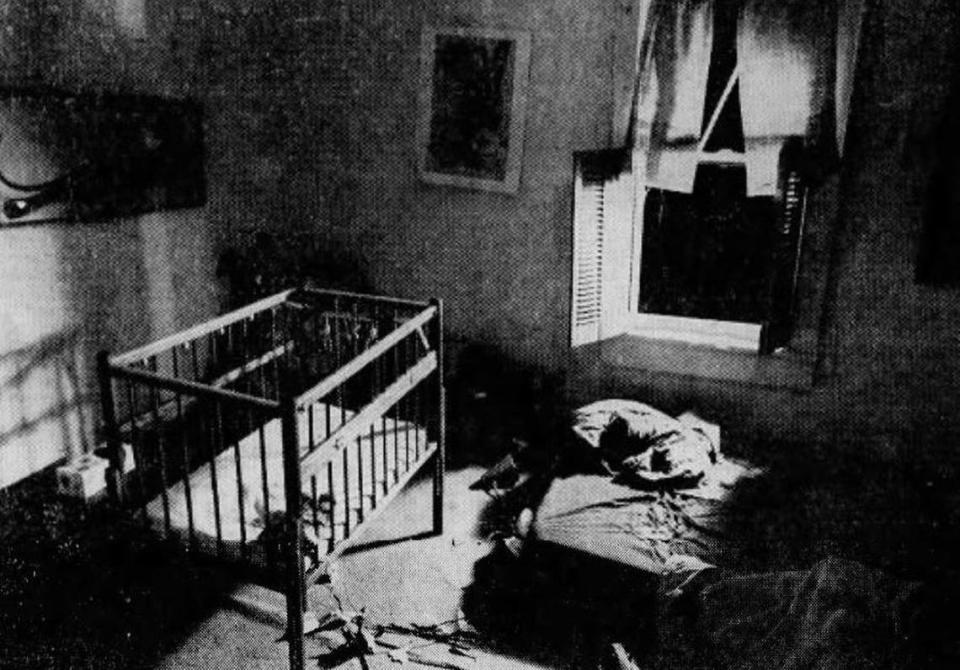

Days before the KUAC hearings resumed at the Pike County courthouse in December 1968, someone tossed lit sticks of dynamite outside the McSurelys’ bedroom late at night, damaging their house. The couple and their infant son, Victor, were showered with glass shards when the explosion shattered the window.

“We’re lucky that it was December, so it was cold and we all had blankets on us,” McSurely told the Herald-Leader. “I can remember pulling the blankets off our son and seeing what seemed like a thousand shards of glass fall off.”

The family fled Kentucky. No arrests were ever made.

The KUAC hearings share part of the blame for the bombing, McSurely said.

“There’s no question in my mind that KUAC raised the temperature in the county and got those people upset with us all over again, just as it intended to,” McSurely said.

“That was the whole point of those hearings, to make people suspicious and to turn them against each other,” he said.

Eastern Kentucky coal operators wanted to chase away the anti-poverty workers because they had started organizing local land owners against strip-mining and other exploitative practices, said Thomas Kiffmeyer, an historian at Morehead State University.

KUAC, charged with rooting out communists in Kentucky, was a useful tool, Kiffmeyer said.

“I don’t think the Pike County officials really thought they were communists,” he said. “They thought they were on the Left. But they didn’t think they communists, and they knew perfectly well they weren’t conspiring to overthrow the government of Pike County. It was very cynical.”

Snooping through their books

In the following exchange from the Pikeville hearings in October 1968, KUAC staff lawyer John Tim McCall questioned James Madison Compton of Pike County’s Shelby Creek community.

Compton, a store owner, had been the McSurelys’ landlord. It was Compton who went into their house when they were gone one day, snooped through their library and reported his concerns about their politics to the sheriff.

That led to a search warrant on suspicion of sedition and the subsequent sheriff’s raid.

Compton: “People were complaining about me having them there, so I was afraid it would hurt my business. I would get calls at night as to why I had communists on my property. But at that time, I didn’t know they were communists or didn’t know that they had any dealings with communists.”

“I knew they was different from what we were, so I told Al (Alan McSurely) I needed the house and asked him to move. I had my sister to come in to occupy the house.”

Inside, “there was all this literature and all. Well, it was on the communist line. There was a lot of books on Russia and some on China and all kinds of magazines and newspapers.”

McCall: “Would you describe any of the pictures that you recall?”

Compton: “Well, most of the pictures were either a white woman with colored children or a colored woman with white children, or it was colored and white, mixed.”

McCall: “Do you recall any of the slogans that were on the wall?”

Compton: “Well, something about adopting a Negro from Mississippi and something about Black power..”

McCall: “Were you having any problems, any race problems in the area at that time? In other words, Negro problems?”

Compton: “No, there was several colored back there, but we never did have no problems with them.”

McCall: “Do you know why they had these race slogans on the walls?”

Compton: “Nothing, only what I can imagine in my own mind.”

McCall: “You previously have made the statement that these people were different. What you mean by ‘they were different’ — in the way they acted?”

Compton: “Well, their actions and so on. They didn’t clean up as we did, they didn’t shave, they needed haircuts. They was kind of slouchy and they was continuously going around — see, they didn’t talk much to mature people. It was mostly the kids in the neighborhood they seemed to be after.”

McCall: “Did they have discussions with you about any of their philosophies about the country?”

Compton: “Well, yes, they believed that money ought to be taken from the rich and given to the poor. It ought to be divided.”

McCall: “Did they ever make any statements about their philosophies?”

Compton: “Well, they didn’t believe in a hereafter.”

McCall: “Did you ever ask Mr. McSurely or (fellow anti-poverty worker Joe) Mulloy (also charged with sedition after a raid on his house) whether they were communists?”

Compton: “No, I didn’t. After these calls started coming in, I moved them out.”

McCall: “Did you personally read any of the literature that you previously described?”

Compton: “Well, now, I didn’t read nothing in full. There was so much of it there and I had a short time and I didn’t cover nothing in full. But I did glance at it enough to know what it was.”

“It upset me so bad at the time that I didn’t do too thorough a job on it. I come back home and called the high sheriff and told him what was back there and asked him what could be done about it.”

“After a time, I got a call from Thomas Ratliff to come to the Pike County courthouse. And I come to the courthouse and there were, I guess, 50 or 60 other people present. They had a hearing and I swore out search warrants and they made the raid.”

McCall: “Thank you very much, Mr. Compton.”