Director William Friedkin's Controversial Gay Film Legacy

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

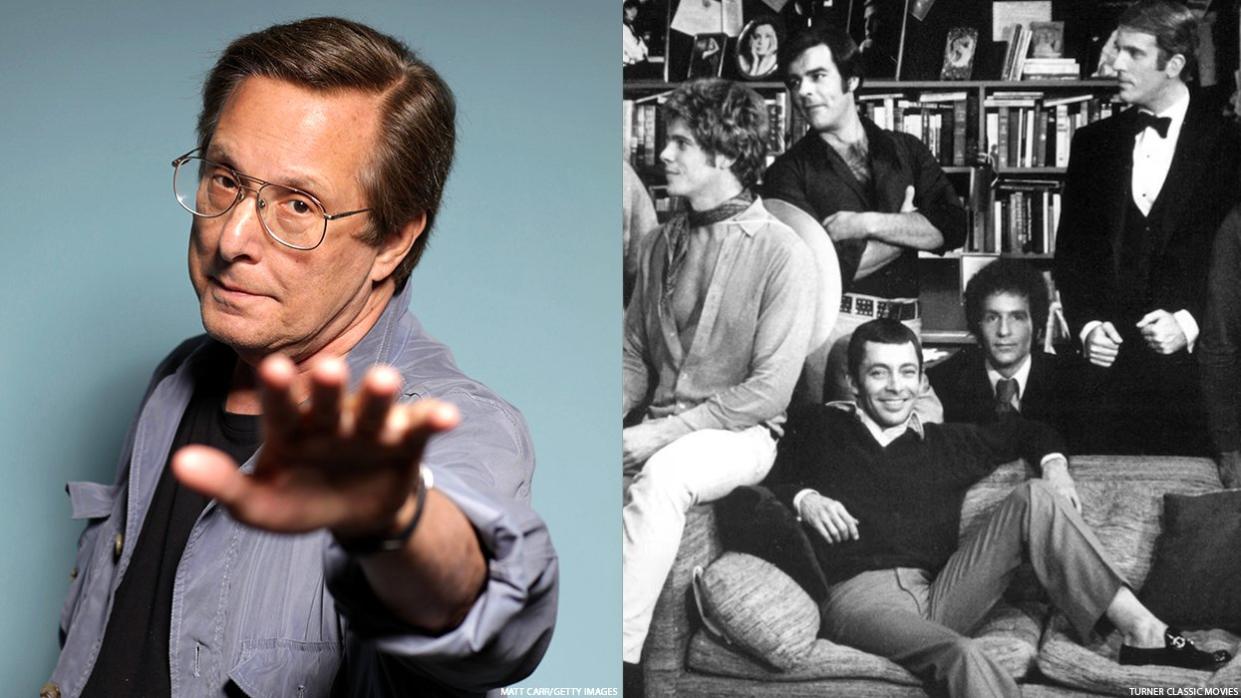

Film director William Friedkin, who died Monday at age 87, was best known for The French Connection and The Exorcist, but he also directed two high-profile and controversial gay-themed movies — The Boys in the Band and Cruising.

Both have received some condemnation of how they portrayed gay and bisexual men, but both have also been reevaluated in recent years.

The Boys in the Band came out in 1970, two years after the Mart Crowley play it was based on premiered off-Broadway; Crowley also wrote the screenplay. The film starred all the actors who originated the roles onstage. It depicts a group of New York City gay and bi friends meeting for a birthday party for one of their number. They drink excessively, use recreational drugs, and snipe at each other. Friedkin, who was straight, once claimed to have been cruised by a gay man on Fire Island, which he was visiting as research for doing the film, and “getting out of there as quickly as my legs would take me,” according to a 1980 article by Edward Guthmann in the journal Cinéaste.

The play and the film were criticized at the time — and later — for portraying queer men as dysfunctional and self-loathing. The objections were mainly to the source material, not Friedkin’s direction. “Crowley has a good, minor talent for comedy-of-insult, and for creating enough interest, by way of small character revelations, to maintain minimum suspense,” Vincent Canby wrote in The New York Times upon the movie’s release .”There is something basically unpleasant, however, about a play that seems to have been created in an inspiration of love-hate and that finally does nothing more than exploit its (I assume) sincerely conceived stereotypes.” He did praise Friedkin’s direction as “clean and direct, and, under the circumstances, effective” in a film that takes place mostly in one space, party host Michael’s apartment.

However, Village Voice critic Andrew Sarris found the characters more sympathetic — but pleading too much for viewers' acceptance. “Crowley wants to have it both ways, describing the vitality and vivacity of the homosexual milieu with his left hand while bemoaning the immaturity and instability of the homosexual condition with his right,” Sarris wrote in 1970. “Ultimately … the characters bid blatantly for audience sympathy.”

Crowley’s work was reevaluated in light of a 2018 Broadway production, starring all queer actors, and 2020 Netflix film with the same cast. From a 21st-century perspective, viewers could see that the problems of the men in Boys came not from being gay but from living in a homophobic world. And as Crowley said, he was not trying to represent all gay men.

Friedkin was relatively unknown when The Boys in the Band was released, but by the time of Cruising he was acclaimed and famous. He’d won the Best Director Academy Award for The French Connection, which came out in 1971, and been nominated for The Exorcist, a box-office smash in 1973. When it was reported that he was shooting Cruising, for which he was the screenwriter as well as director, gay activists were deeply concerned.

Cruising, based on a 1970 novel by Gerald Walker, tells the story of an ostensibly straight New York City police officer going undercover in S&M bars in pursuit of a serial killer of gay men. Al Pacino was cast as the policeman. Arthur Bell, a Village Voice writer, penned a column describing Friedkin’s Fire Island story, and went on to say that Cruising “promises to be the most oppressive, ugly, bigoted look at homosexuality ever presented on the screen, the worst possible nightmare of the uptight straight, and a validation of Anita Bryant’s hate campaign.”

Bell encouraged gay people to protest at the film’s New York locations, which they did. Bell said he’d put out a contract on the movie; Friedkin said it would actually “alleviate the violence against gays in the country.” Some activists tried to stop its release, but United Artists did release it. Guthmann observed that it neither incited violence nor impressed film reviewers.

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times wrote that “the plot structure is a mess” and that the movie implies that Pacino’s character may be doubting his heterosexuality but never explores this issue in depth. It “seems to make a conscious decision not to declare itself on its central subject,” Ebert remarked.

Some critics demonstrated more than a touch of homophobia in their reviews, describing the S&M bar settings as “bizarre,” while Canby said Friedkin portrays them “with far more leering attention to detail than most people will find necessary.” However, there were reports that Friedkin cut much sexually explicit footage from the film in order to avoid a X rating. The 2013 movie Interior. Leather Bar, from James Franco and Travis Mathews, reimagined this footage.

In the new millennium, reviewers were finding Cruising homophobic, just as the activists against it were saying during its making. “In its shameless excavation and exploitation of the killer-queen archetype — the homosexual so riddled with self-loathing and guilt that they feel an insatiable urge to kill and punish others — the film is bad politics and dodgy, flawed filmmaking, but it’s weirdly resonant and thoroughly haunting all the same,” A.V. Club contributor Nathan Lee wrote in 2007.

New York Times writer Scott Tobias, recommending Friedkin films to stream in the wake of the director’s death, acknowledged the problems with Cruising but found some things to praise about it. “It’s an understatement to say that Friedkin does not approach the material with the sensitivity his doubters might have wished for, but the locations have an almost tactile griminess to them, and Pacino’s performance roils with inner torment,” he said.

Friedkin, during the making of Cruising and after, defended himself against allegations of homophobia. “Anyone who knows me or knows anything about me knows that I am not antigay,” he told Janet Maslin in The New York Times in 1979. “I don’t make a film because I’m against something. For that matter, I don’t make a film because I’m for something — don't make propaganda. If anything, all the films I’ve made are enormously ambiguous.”

And some reviewers have recently said that Cruising deserves reevaluation. “It’s clear that the film is intended as a subversive take on the status quo of its time,” Peyton Brock, a trans woman and LGBTQ+ rights activist, wrote at Collider. She added, “Despite the film showing the gay BDSM scene as dark and mysterious, it never condemns the scene's members; rather, only the killers and wrong-doers who would invade it.”

“Friedkin wasn’t wrong for making a movie that ultimately tells a subversive and risque story, and the protestors were not wrong for putting up their guards against another perceived attack on their community, an all too real threat at the time,” she went on. “However, it’s time to put aside the prejudices and judgments of the past, and to allow Friedkin’s film to speak for itself.” Whether viewers see it as “a subversive statement against police and the status quo; a well-made, engaging thriller; a compelling time capsule of the 70’s/80’s NYC gay BDSM scene; or all of the above, Cruising is worth a whole lot more than reactionary condemnation,” Brock concluded.