How discovery in basement led to long overdue Purple Heart for Taunton WW I soldier

DIGHTON — It only took 91 years for Peter Joseph Hebert to be awarded his Purple Heart.

The Taunton native, who died in 1976 at age 81, fought in World War I as part of the U.S. Army’s 6th Engineers regiment assigned to the 3rd Infantry Division.

Hebert was injured on July 16, 1918, probably as the result of a gas attack launched by German troops, during the second day of the Second Battle of the Marne.

“I think he was badly gassed,” said his grandson and military history buff Vinnie Hebert of Dighton.

And although he’s convinced that his grandfather likely wore a gas mask to prevent inhaling lethal, chemical warfare gasses such as mustard gas, soldiers still couldn’t avoid serious skin burns and blistering on their bodies as the gas penetrated their clothing.

Hebert this past summer provided the U.S. Army with documentation pertaining to his paternal grandfather’s military service and the fact that he had been injured. His perseverance paid off when the Army sent him a Purple Heart medal inscribed with his grandfather’s name.

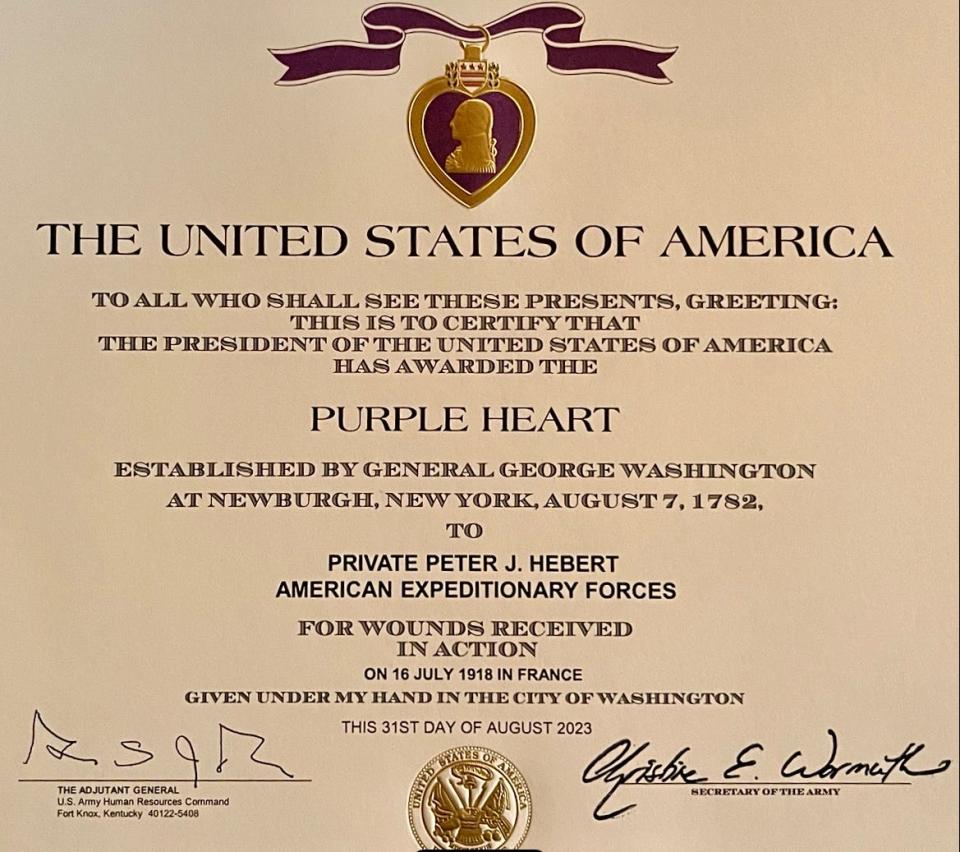

They also at the same time mailed a certificate signed on Aug. 31 recognizing that Peter J. Hebert was wounded in action in France on July 16, 1918.

In addition to that, the Army arranged an award presentation ceremony with military dignitaries and elected officials at the Taunton Armory on Honorable Gordon M. Owen Riverway.

'Rattle people’s cages' Here's why D-R superintendent went on Fox News twice amid furor over field hockey injury

Purple Heart history

The first version of the Purple Heart was created by the Continental Congress in 1780 and was known as the Fidelity Medallion. Two years later it was replaced when President George Washington created the Badge of Military Merit.The award eventually was revived in 1932 when it officially became known as the Purple Heart. Its first recipient was the Army’s then chief of staff and future general Douglas MacArthur. But it was up to surviving soldiers of the First World War or their families to request a Purple Heart in order to receive one.

Soldiers who were injured but survived, along with families of soldiers killed in World War I, beginning in 1919 received what was then known as a Presidential Wound and Killed in Action Certificate.

President Woodrow Wilson was responsible for the creation of that large, ornate certificate featuring the image of a female figure known as Columbia, who is seen touching the shoulder of a kneeling soldier with a sword while holding the certificate aloft in her other hand.

“Columbia Gives to Her Son the Accolade of the New Chivalry of Humanity,” the certificate’s inscription reads.

Does Lake Sabbatia need a speed limit? Taunton cracks down with Lake Sabbatia speed limit and a lot more. Will it work?

Hebert, 64, says he discovered his grandfather’s wound certificate, bearing President Wilson’s signature, inside a cardboard cylinder that had been mailed to his grandfather after he returned home to Taunton from the war.

Hebert took possession of the cylinder and other wartime documents — including his grandfather’s military dog tags and 1919 Army discharge paper (held together with Scotch tape) — a few years ago, courtesy of his father Vincent and mother Liz when they moved into their daughter’s house in Somerset.

How many people died in World War I?

Hebert says he’s not surprised that his grandfather, who enlisted in the Army in October 1917 when he was 22, apparently didn’t care about putting his military documents on display.

“I think a lot of veterans back then didn’t want to think about what they had been through. It was a horrific war,” he said.

As many as nine to 10 million soldiers on both sides and close to a total of eight million civilians died as result of warfare, disease or famine in World War I.

What're houses selling for near Taunton? Weekly home sales: Charming investment property in Taunton sells for over $700K

Writing a history of his grandfather's service

Hebert, who previously has written a gothic horror novel and a novella in a similar vein, said he decided to try to write a nonfiction account of his grandfather’s life and his military exploits in France.

In addition to poring over a handful of military technical books he ordered through Amazon, he perused military historical data via the Fold3 online database.

Hebert also was enormously impressed with the Stephen Harris book “Rock of the Marne,” the name of which is associated with 3rd Infantry Division troops for their tenacity and determination during the Second Battle of the Marne.

“The Third Division would not give up,” Hebert said. “The Germans were afraid of them, but the Germans were also coming on and would not give up.”

According to military historians, the four-day Second Battle of the Marne marked the end of a string of German battlefield conquests and led to a succession of decisive Allied victories.

Four months later, on Nov. 11, Germany followed the example of its former Central Powers allies – Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire – and signed an armistice ending the brutal, four-year European war.

Getting the Purple Heart

A turning point for Hebert came when he decided to contact Harris to ask his advice. Hebert said he was pleasantly surprised, if not downright amazed, when the noted author got back to him within a matter of hours.

Hebert says until he spoke with Harris he did not know that WWI wounded veterans like his grandfather were entitled to receive a Purple Heart, including posthumously.

On the advice of Harris, he collected whatever pertinent data he could gather from the National Archives and Records Administration. Hebert also contacted the National Purple Heart Hall of Honor in New York state and then the U.S. Army.

“The Army was so good. They got back to me in hours,” Hebert said. “I told them that my father was 90, and it only took them six weeks instead of three months to get everything to me.”

He said this also included delivery of a small French military pin.

A brutal war

Hebert said he doesn’t know how long it took for his grandfather to fully recover from his wounds. He said records do show that he arrived back in the United States from France disembarking at Newport News, Virginia on Jan. 1, 1918.

Two weeks later, Hebert said, his grandfather was discharged from military duty on his 24th birthday. He came back to Taunton and four years later, in 1922, married the former Helen Cotter, who was born in Ireland. Peter Hebert worked as a professional carpenter, and the couple raised nine children.

Hebert said his motivation for gathering historical information about his grandfather and World War I was twofold.

He said more people should know just how brutal and punishing the early 20th century war was, with its trench warfare, tanks, inadequate medical resources and worldwide influenza epidemic.

Distant relationship and suspicions of PTSD

But he also thinks that his grandfather, who he barely came to know as he was growing up in Taunton, could well have suffered to some extent from what was then called “shell shock,” and which decades later came to be known as post-traumatic stress disorder.

Hebert said his grandfather was cold and distant to all six of his grandchildren.

“My first memory of him was fear. He was 5'3” and wore glasses and was very serious,” Hebert said. “And he was a chain smoker. He would smoke non-filter Camels and light one cigarette to another.”

Hebert said his grandfather managed to support his family despite the fact that he was an alcoholic with a temper who didn’t hesitate to take out his anger and frustration on his wife.

At one point, he said, his grandmother consulted with her priest as to whether she should leave her husband, but he urged her to stay for the sake of the children.

“I think he probably did have PTSD,” Hebert said.

“I would think, ‘Why was he like that?’ I just couldn’t understand why. Was he a happy-go-lucky, nice guy before the war? But when you see someone blown to pieces and you’re gassed, what does that do to you?”

“He had demons,” Hebert added. “And that was probably how he tried to drown them out,” referring to his grandfather’s drinking problem.

Horrors of war could explain grandfather's rage

Hebert, 64, is originally from Taunton but now resides in North Dighton with his wife Debbie. He retired a year and a half ago after working as a global product manager for the Franklin biotech storage company Hamilton Storage, which did a lot of work for Moderna, Pfizer and the Mayo Clinic, he said.

Before that he said he worked for more than 10 years for Ametek Brookfield, a cryogenic energy storage company in Middleboro.

Besides delving into military history, Hebert also sings and plays saxophone and drums in a band called Tumbling Dice.

With understanding comes forgiveness

Peter Hebert is buried in St. Joseph Cemetery on East Britannia Street. His grandson Vinnie says he’s never visited the gravesite.

But the more he ponders the chances that his grandfather’s personality and behavior might have been shaped by his inability to fully recover, emotionally and psychologically, from his World War I experiences, the more he’s willing to reconsider.

“It’s on my list of things to do,” Hebert said.

This article originally appeared on The Enterprise: Taunton WW I veteran gets long-overdue Purple Heart