‘Disgraceful’: Tempers run high as Jackson County seeks compromise on conversion therapy

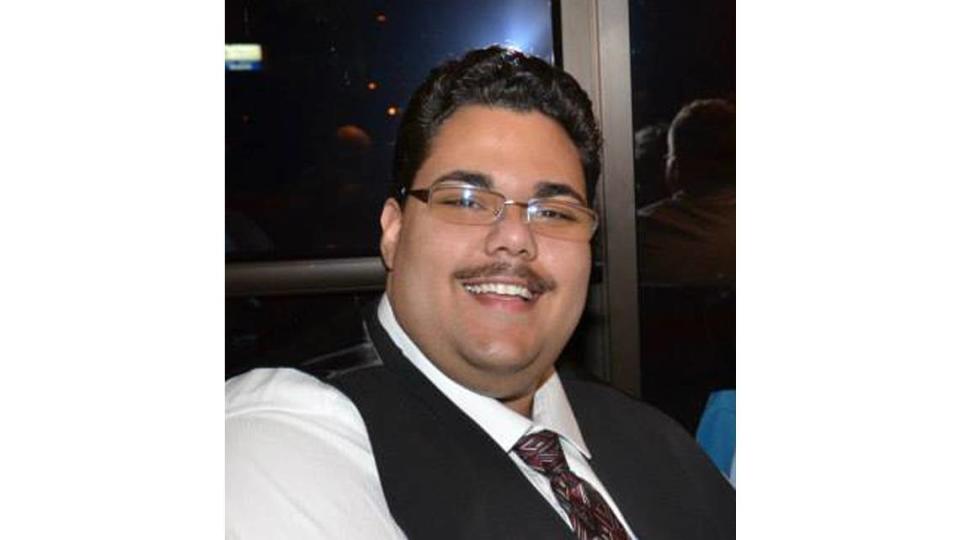

Jalen Anderson says that from the time he was 12 to almost 15 years old he was tortured physically and mentally by adults at the private Christian school he attended in Independence.

The pastor called him a “sissy” and, suspecting he might be gay, the school staff tried to ensure he’d grow up straight by employing the now discredited practice known as conversion therapy.

He and three friends were forced to sit in the cold with their arms tied to concrete blocks while quoting Bible verses. They were shown heterosexual pornography and told they were sinful and hated by God, he said.

The other three, two were gay and one was lesbian, would later take their own lives, he said. Anderson, who said he identifies as straight, remains traumatized two decades later.

“This is child abuse,” he explained as he told that story to his eight colleagues on the Jackson County Legislature.

For three months the county’s main governing body had been quietly mulling Anderson’s proposal to ban counselors and other licensed professionals from employing conversion therapy in an attempt to turn LGBTQ kids straight.

The process has taken too long, he thought, but he was hopeful. So when his proposed ordinance failed last week by single vote, he erupted.

“Disgraceful!” Anderson thundered from his chair in the legislative chambers at the downtown courthouse. “Disgraceful! This entire body — disgraceful!”

Others thought so as well, most notably County Executive Frank White, who has been lighting the courthouse with rainbow colors since Sunday to call attention to what he called the legislature’s “failure to pass a simple conversion therapy ban.”

Pressure from within and outside county government helped revive discussion at the legislature this week. On Monday, a slim majority advanced a cobbled-together version of Anderson’s proposal that he could not support and White promised to veto if it passes.

It included a provision for notifying would-be violators of the ordinance that conversion therapy was being banned without specifying how to notify the public, which White said could make the county vulnerable to lawsuits.

Another add-on said the ordinance would not take effect for three months, which is not county policy. New ordinances typically take effect immediately.

“This is bad legislation,” Anderson said in an interview. “It has not been thought through.”

‘Shenanigans’

Calling this version unenforceable in its current form, White promised he would veto it, should the legislature give final passage this coming Monday.

With that threat hanging, Anderson and co-sponsor Manny Abarca were negotiating over the phone all this week with other members to find language that a majority will support and White will sign into law.

On Wednesday afternoon, a tentative agreement was reached on the basic points of contention that Anderson feels he could support.

“As long as the other side keeps its word,” he said in a text.

Asked for an update, Abarca texted a fingers-crossed emoji on Wednesday evening. But discussions were still going on late Thursday morning, a few hours before the clerk of the legislature posts next week’s agenda.

“I can’t confirm anything at the moment,” Abarca said in a text. “It seems there are still discussion to be had.”

Everyone on the legislature has cast at least one vote in favor of banning conversion therapy over the past two weeks. But some have also abstained or voted no to one or more of the six versions that have come before the body. All forbid conversion therapy being performed by licensed counselors, therapists and mental health professionals. All exempt parents and grandparents from the prohibition.

None bar religious leaders from exerting pressure on youths about their sexuality or gender identity. Violations are punishable by a fine, not jail time.

The disagreements have been over the fine points, although few legislators have voiced their disagreements publicly. Chairman DaRon McGee, Venessa Huskey and Donna Peyton never explained why they abstained on that first vote that Anderson felt was so disgraceful. They later voted for the version that White claimed would open the county to litigation.

“Shenanigans,” was freshman Republican legislator Sean Smith’s one-word observation at this week’s meeting to describe what he’s observed, but declined to explain when asked about it later.

There’s been some confusion, too. No one seems to know, for instance, how the 90-day delay in enforcement language got into the proposed ordinance that advanced Monday and is now being amended.

Was it the work of a single legislator who won’t come forward, or was it sloppiness? Neither the county counselor’s office nor Abarca, who sponsored the ordinance, can explain.

Anderson said Wednesday that the compromise version would eliminate the 90-day provision and other language added to his original version. A separate resolution sets out instruction for a one-time public notice of the new law.

Abarca hopes Jackson County will soon join the half dozen metro-area cities that have banned conversion therapy in recent years.

But if for some reason that doesn’t happen Monday, the issue is not going to go away. So promises Justice Horn, chairman of the Kansas City LGBTQ Commission, which has backed Anderson’s proposal.

“As Jalen said, it’ll be reintroduced every single week,” he said. “This needs to be done. The voters and the electorate want it to happen. The county is going to be lit rainbow every night until we get this done.”