Disinformation Researchers Are Feeling The Heat Ahead Of 2024

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Next year might be one of the worst times we have seen, and maybe the worst time we have seen, for the spread of election-related mis- and disinformation,” one expert told HuffPost.

Kate Starbird had been studying online conspiracy theories for years when she realized last year that she was at the center of one.

“I can recognize a good conspiracy theory,” she recalled to HuffPost. “I’ve been studying them a long time.”

Right-wing journalists and politicians had begun the process of falsely characterizing Starbird’s work — which focused on viral disinformation about the 2020 election — as the beating heart of a government censorship operation. The theory was that researchers working to investigate and flag viral rumors and conspiracy theories had acted as pass-throughs for overzealous bureaucrats, pressuring social media platforms to silence supporters of former President Donald Trump.

The year that followed has changed the field of disinformation research entirely.

Republicans gained control of the House of Representatives last fall, and Rep. Jim Jordan (R-Ohio) — a key player in Trump’s attempt to overturn the 2020 election results — began leading a “Weaponization of the Federal Government” committee shortly thereafter. Among other things, the group zeroed in on researchers who rang alarm bells about Trump’s “Big Lie” that the election had been stolen.

Around the same time, conservatives cited billionaire Elon Musk’s release of the so-called “Twitter Files,” which consisted of internal discussions on moderation decisions prior to his ownership of the company, to select journalists as evidence of government censorship. Despite legitimateconcerns about the nature of the federal government’s relationship with social media platforms, the documents never bore out accusations that government officials demanded Twitter take down certain posts or ideologies.

The fight spilled into Congress and the courts: Disinformation researchers became the targets of Republican records requests, subpoenas and lawsuits, and communication between some researchers and government officials was briefly restricted — the result of a federal judge’s order that was later narrowed. Conservative litigators accused Starbird and others in the field of being part of a “mass censorship” operation, and the political attacks moved some researchers to avoid the public spotlight altogether.

It is a really tenuous moment in terms of countering disinformation because the platforms see a lot of downside and not so much upside.Samir Jain, co-author of CDT report on counter-election-disinformation initiatives

Disinformation researchers who spoke to HuffPost summarized the past year of legal and political attacks in two words: “Chilling effect.” And it’s ongoing. Amid widespread layoffs at social media platforms, new limitations on data access, the antagonism of Musk’s regime at X (formerly Twitter), and complacency from some who think the dangers of Trump’s election denialism have passed, the field — and the concept of content moderation more generally — is in a period of upheaval that may impact the 2024 presidential election and beyond.

Even close partnerships between researchers and social media platforms are fraying, with experts more frequently opting to address the public directly with their work. The platforms, in turn, are heading into the 2024 presidential cycle — and scores of other elections around the globe — without the labor base they’ve used to address false and misleading content in the past.

Many in the field are coming to terms with a hard truth: The web will likely be inundated with lies about the political process yet again, and fact-checkers and content moderators risk being out-gunned.

“Right now, it is a really tenuous moment in terms of countering disinformation because the platforms see a lot of downside and not so much upside,” said Samir Jain, co-author of a recent Center for Democracy and Technology report on counter-election-disinformation initiatives. “Next year might be one of the worst times we have seen, and maybe the worst time we have seen, for the spread of election-related mis- and disinformation.”

Ending The ‘Golden Age’ Of Access

After Trump was elected in 2016, social media companies invested in content moderation, fact-checking and partnerships with third-party groups meant to keep election disinformation off of their platforms.

In the years that followed, using spare cash from sky-high revenue, the platforms invested in combating that harm. With the help of civil society groups, journalists, academics and researchers, tech companies introduced a mix of fact-checking initiatives and formalized internal content moderation processes.

“I unfortunately think we’ll look back on the last five years as a Golden Age of Tech Company access and cooperation,” Kate Klonick, a law professor specializing in online speech, wrote earlier this year.

The investment from platforms hasn’t lasted. Academics and nonprofit researchers eventually began realizing their contacts at tech companies weren’t responding to their alerts about harmful disinformation — the result of this year’s historic big tech layoffs, particularly oncontent moderation teams.

“We’ve been able to rely even less on tech platforms enforcing their civic integrity policies,” said Emma Steiner, the information accountability project manager at Common Cause, a left-leaning watchdog group. “Recent layoffs have shown that there’s fewer and fewer staff for us to interact with, or even get in touch with, about things we find that are in violation of their previously stated policies.”

We’ve been able to rely even less on tech platforms enforcing their civic integrity policies.Emma Steiner, information accountability project manager at Common Cause

Some companies, like Meta, which owns Instagram and Facebook, insist that trust-and-safety cuts don’t reflect a philosophical change. “We are laser-focused on tackling industrywide challenges,” one spokesperson for the company told The New York Times last month.

Others, like Musk’s X, are less diplomatic.

“Oh you mean the ‘Election Integrity’ Team that was undermining election integrity? Yeah, they’re gone,” Musk wrote last month, confirming cuts to the team that had been tasked with combating disinformation concerning elections. Four members were let go, including the group’s leader.

More broadly, Musk has rolled back much of what made X a source for reliable breaking news, including by introducing “verified” badges for nearly anyone willing to pay for one, incentivizing viral — and often untrustworthy — accounts with a new monetization option, and urging right-wing figures who’d previously been banned from the platform to return.

In August, X filed a lawsuit against an anti-hate speech group, the Center for Countering Digital Hate, accusing the organization of falsely depicting the platform as “overwhelmed with harmful content” as part of an effort “to censor viewpoints that CCDH disagrees with.” Musk also left the European Union’s voluntary anti-disinformation code. In August, the EU’s Digital Services Act, which includes anti-disinformation provisions, went into effect, but Musk has responded to warnings from the EU about X’s moderation practices by bickering with an EU official online.

Earlier this year, Musk also started charging thousands of dollars for access to X’s API — or application programming interface, a behind-the-scenes stream of the data that flows through websites. That data used to be free for academics, providing a valuable look at real-time information. Now, Starbird said, monitoring X is like looking through a “tiny window.”

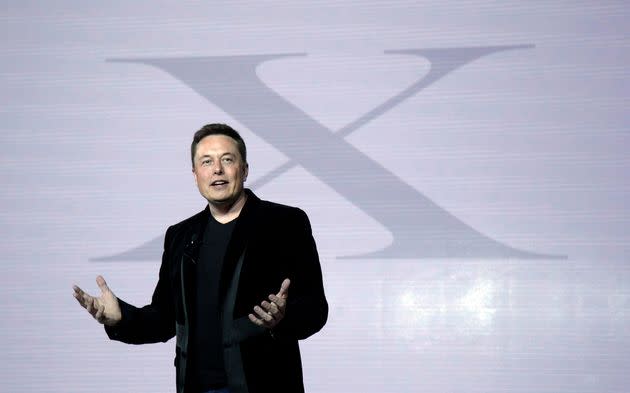

Twitter CEO Elon Musk has rolled back much of what made the company, now known as X, a source for reliable breaking news.

In addition to the economic and logistical hurdles, legal and political attacks against researchers further bogged down their work as Republican legislators and their allies misconstrued their efforts to cut through rumors and lies about the 2020 election as a censorship operation.

Disinformation researchers were dragged before congressional investigators, and Republicans requested the records of those who worked at public universities — including the University of Washington, where Starbird is the director of the Center for an Informed Public. The owner of Gateway Pundit, one of the most active conspiracy theory mills on the right-wing internet, sued Starbird and others, alleging that their work tracking disinformation about the 2020 election was “probably the largest mass-surveillance and mass-censorship program in American history.” America First Legal, former Trump aide Stephen Miller’s outfit, is representing the website.

Similar allegations in a different lawsuit brought by the states of Missouri and Louisiana have now reached a federal appeals court in the form of Missouri v. Biden. In July, a district court judge issued a preliminary injunction in the suit, ordering the federal government to stop flagging disinformation to social media platforms — and to stop contacting groups like the Election Integrity Partnership, a coalition in which Starbird’s center was a key member, in any effort to do the same. Last month, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals found that the Biden administration had, in fact, likely violated the First Amendment by asking platforms to remove certain false posts — but it also excluded EIP and other third-party groups from the injunction, calling the district court’s order “overbroad.”

On top of all that, the Supreme Court announced last month that it would hear two new laws out of Texas and Florida that would restrict content moderation options for social media platforms of a certain size.

The political and legal attacks from the right — records requests, lawsuits, congressional subpoenas — seem to have left the biggest mark on disinformation researchers, particularly those from smaller organizations without resources for potentially large legal bills.

One anonymous individual quoted in the Center for Democracy and Technology report, faced with a congressional subpoena from the House Judiciary Committee, was lucky enough to find pro-bono legal help through a personal connection.

“Nobody knew what to do from a legal perspective,” the person said. “Our entire legal strategy was, ‘talk to every lawyer you have a connection with.’”

Disinformation researchers, in other words, are now being attacked by the very forces they once studied from the sidelines, and it’s affecting their work.

“The reason these changes are happening is platforms are feeling political pressure to move away from moderation; researchers are feeling political pressure to not do this type of research,” Starbird told HuffPost. “The people that use propaganda and disinformation to advance their interests — they don’t want people to address those problems, and if it works for them to use political pressure to make sure that they’re able to continue to use those techniques, they’re going to do that.”

The reason these changes are happening is platforms are feeling political pressure to move away from moderation; researchers are feeling political pressure to not do this type of research.Kate Starbird, director, Center for an Informed Public at the University of Washington

What Now?

Faced with strained relationships with platforms and legal and political pressure to cut contact with government officials, some researchers have sought to change course, addressing more of their work directly to the public.

“Into 2022, our focus was attempting to combat disinformation and disrupt it when it appeared. But we’re finding now that this is somewhat of an overwhelming task, something that can be almost impossible to contain,” Steiner said. She added that Common Cause was moving toward a longer-term project of information literacy and efforts to reduce polarization “rather than trying to play ‘gotcha’ with disinformation narratives that appear one day, go viral, and then disappear.”

Starbird said she’d notice a broader shift in the field, including at the Election Integrity Partnership.

“We’re kind of moving towards all output being a stream that anyone can tap into,” she said. “We’ll be communicating with the public, we’ll be communicating with journalists. If platforms want to look at this, they can too, but it’s just going to be the same feed for everybody.”

Despite the recent turbulence, some in the field have publicly cautioned against doom-and-gloom talk about the future of disinformation work. Starbird, in particular, wrote in the Seattle Times that, contrary to a recent Washington Post headline, “no one I know in our field is ‘buckling’ or backing down.”

Katie Harbath, former director of Facebook’s public policy team, has warned against black-and-white analyses of tech policy ahead of 2024. For example, she said, various companies have rolled back policies against denying the legitimacy of the 2020 U.S. presidential election — but she thinks they’ve “left their options open” if similar false claims come up in 2024.

“As I’m watching all of this, sometimes I think the coverage is trying to fit into too neat of a binary, of they’re-doing-enough or they’re-not-doing-enough,” she told HuffPost. “And we just don’t know yet.”

Still, Harbath acknowledged that layoffs alone had diminished platforms’ capability to fight false claims, particularly with so many elections scheduled worldwide in 2024.

“The pure number of elections [worldwide] means these companies are going to have to prioritize,” she said. “And we don’t know from them what they are going to prioritize. I worry that the U.S. election is going to suck up so much of the oxygen — and the EU elections, because there’s actual regulation there that they have to comply with — what does that then mean for India, Indonesia, Mexico, Taiwan?”

Harbath and several others stressed the resilience of researchers in the disinformation field. But the nature of their work is also changing when it seems to be needed most. Starbird, for example, said she didn’t have a good answer for people seeking information about the war in Israel and Gaza, given X’s failures on that front.

During a launch event for the Center for Democracy and Technology report, Rebekah Tromble, director of George Washington University’s Institute for Data, Democracy, and Politics, articulated the feeling in the field. She called for researchers to ask themselves “difficult questions” and wondered aloud whether the yearslong focus on “fake news” and mis- and disinformation had “created a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

The recent pressures on the field, she said, “give us an opportunity to think a bit more critically about how the work fits into the larger public dialogue.” To that end, she echoed an admonition from Harbath, who was also on the call, about how the field should look for answers amid incoming fire: “Panic responsibly.”