Divided Field Could Hurt Progressives In Chicago Mayoral Race

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

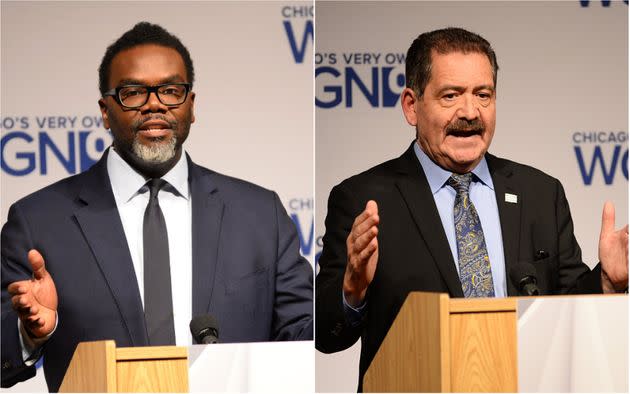

Cook County Commissioner Brandon Johnson (left) is showing signs of a late surge against U.S. Rep. Jesús "Chuy" García. Some of his supporters are frustrated with García for entering the race after Johnson announced.

CHICAGO ― As the Chicago mayoral election approaches, progressives are facing the possibility that a glut of left-leaning candidates makes it more likely that a moderate or conservative contender will hold power at City Hall.

Nine candidates are on the ballot in Tuesday’s citywide, nonpartisan elections: Mayor Lori Lightfoot; Paul Vallas, former CEO of Chicago Public Schools; U.S. Rep. Jesús “Chuy” García (D-Ill.); Cook County Commissioner Brandon Johnson (D); businessman Willie Wilson; Illinois state Rep. Kambium “Kam” Buckner (D); and Chicago City Council members Sophia King (D) and Roderick “Rod” Sawyer (D).

Among the five top contenders, both Johnson and García have a credible claim to the progressive mantle. Should no one get an outright majority of the vote ― as is widely expected ― there will be a two-person runoff on April 4.

But in a recent public poll, Vallas, a dyed-in-the-wool centrist who once flirted with becoming a Republican, and Lightfoot, a mainstream liberal unpopular with the left, were the two candidates on track to make the runoff. Johnson and García were due to come in third and fourth place, respectively.

Many earlier polls showed García making the runoff, and mainstream Democratic strategist David Axelrod predicted on Thursday that Johnson, whom he said has the “momentum,” would make the runoff against Vallas.

The precariousness of the situation nonetheless has some on the left worried that the overabundance of progressive candidates has reduced the odds that either García or Johnson advance to the next round. King, Buckner, Sawyer and Green, who are also running to Lightfoot’s left in some respects, could jointly win enough votes to change the margin of victory as well.

Lightfoot “lucked out in that Brandon and Chuy are competing for the same vote,” said Kaitlin Sweeney, a Chicago-area progressive strategist, who is neutral in the race and recently moved outside of the city. “They’re splitting the vote. She’s kind of hoping that they’ll take each other out.”

To some progressives, the situation calls to mind other intra-Democratic contests in which a lack of progressive unity cleared the path for a moderate to prevail.

This past August, former federal prosecutor Dan Goldman bested New York Assembly member Yuh-Line Niou (D) by two percentage points to win the Democratic nomination in New York’s 10th Congressional District. In a field of 12 candidates, the four people besides Niou running to Goldman’s left collectively won 45% of the vote, raising the distinct possibility that if those candidates had consolidated behind Niou ― or someone else ― they could have defeated Goldman.

A similar scenario played out in the Democratic primary in Massachusetts’ 4th Congressional District in 2020, and the New York City mayoral race in 2021.

Morris Katz, a New York City-based progressive consultant, called for progressive organizations to exercise more discipline in cajoling candidates to drop out of crowded races, and for the candidates themselves to prioritize the movement over professional self-interest.

“At a certain point, we’ve got to kind of be asking ourselves: How many more DINOs are we going to elect, because the conservative wing of the party is better at playing primary politics than we are,” said Katz, using an acronym for the pejorative label, “Democrat in name only.”

Clem Balanoff, a progressive former Illinois state representative who is backing García, disputed the idea that left-leaning groups should try to anoint specific candidates.

“Everybody has a right to run,” Balanoff said. “That’s just the way it is.”

García and Johnson have followed parallel career trajectories ― united by their shared ties to the Chicago Teachers Union, or CTU, arguably Chicago’s most influential progressive group.

In 2015, García was then-CTU President Karen Lewis’s hand-picked choice to challenge then-Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, a centrist Democrat with whom the union had repeatedly clashed over his support for charter schools and opposition to additional public-school funding. (Lewis, a towering figure on the Chicago left, had wanted to run herself, but was sidelined by the cancer that would end her life in 2021.)

Johnson, a former CTU organizer, now has the union’s endorsement and considerable financial backing.

The CTU’s support for Johnson over García is emblematic of the price García paid for entering the race late.

Over the summer, many progressives in Chicago were under the impression that García was not planning to run.

Johnson stepped into that void, launching his campaign exploratory committee in September and officially entering the race in late October.

“People approached Chuy García many times, myself included, and consistently what he told us is that he was not planning to run,” said Carlos Ramirez-Rosa, a democratic socialist member of the Chicago City Council supporting Johnson. “Brandon Johnson’s name surfaced as a very strong, viable candidate.”

García’s campaign told HuffPost that García met with Ramirez-Rosa and other Latino Chicago elected officials on Oct. 9, and informed them that while he was still undecided, he was leaning toward running.

Then, shortly after winning reelection to Congress in November, García made it official, announcing his run for mayor.

By that time though, the left was consolidating behind Johnson. He would soon pick up the support of SEIU, the local Working Families Party affiliate United Working Families, and Rep. Delia Ramirez (D-Ill.), a protégé of García’s whom he had helped win a state House in 2018.

“Brandon was there as the progressive standard bearer and then Chuy said, ‘Wait, what about me?’” said one progressive Chicago organizer who requested anonymity for professional reasons. “So the question for Chuy became: Why are you doing this now, and who is this meant to serve?”

In an interview with HuffPost after a candidate debate on Feb. 9, García said he had delayed his entry into the race because of a sense he had that Democrats might hold a narrow majority in the House and that vacating his seat in such a scenario would risk depriving the party of its majority. “My gut wasn’t off that much,” he said.

Notably though, the timing of García’s decision also shields him from the prospect of losing his seat in Congress in the event that he falls short in the race for mayor of Chicago.

Regardless, García is resigned to the idea that that delay cost him some support, but he declined to explicitly criticize Johnson, opine on the left’s divisions, or engage with the suggestion that either he or Johnson should drop out and endorse the other.

He instead made the case that he was there for the left when the city’s politics were more forbidding, referencing his support for then-Mayor Harold Washington in the 1980s, when García won a city council race with Washington’s help; his 2015 run for mayor; and his sponsorship of a slate of progressive reformers up and down the ballot during his 2018 congressional run.

We’ve been at it the longest. We’ve been the most consistent. We have the most scars.U.S. Rep. Jesús "Chuy" García (D-Ill.)

“We’ve been at it the longest. We’ve been the most consistent. We have the most scars,” García said, noting that he hails from a historically conservative part of southwest Chicago. “We were the holdout ― when everybody else came or was taken out by the last remnants of the Chicago machine … We held it down.”

A number of progressive elected officials and labor unions buy García’s argument and are sticking with him, including five members of the Chicago City Council, Rep. Jan Schakowsky (D-Ill.), the deep-pocketed, local operating engineers union, and Stephanie Gadlin, who was communications director for the CTU under Lewis.

“He has been a great champion for his community, and where our interests align, in terms of African Americans here in Chicago, he has been there for us,” said Gadlin, who is Black.

There are significant policy differences between García and Johnson, however.

The left in Chicago has grown stronger, and its demands have grown greater since García ran for mayor in 2015.

Johnson’s policy agenda, which is much more left-wing than García’s, reflects that reality.

If elected, Johnson would likely be the most progressive mayor in Chicago’s history. The heart of Johnson’s agenda is a budget plan that would raise an estimated $1 billion in new revenue through a cluster of progressive tax hikes that are simultaneously designed to spare homeowners an increase in property taxes. He proposes reinstating the city’s employer “head” tax at $4 per employee, levying a special tax on mansions, taxing financial transactions, fining airlines for pollution, increasing hotel taxes, and tightening the city’s use of a real estate tax break.

Johnson would use those funds to create a new, dedicated revenue stream for homelessness services, and reopen city-run mental health clinics as part of a comprehensive, public-health approach to reducing violence. He is also calling for doubling the size of the summer youth employment program to 60,000 jobs.

Affirming that he has a personal stake in reducing crime, Johnson is fond of noting that he and his wife are raising their three kids in the crime-plagued Austin neighborhood.

“No one has a greater incentive in this race for our city to be better, stronger, and safer than someone who is leading the daily experience of working- and middle-class families all over the city of Chicago,” he said.

García, unlike Johnson, is running on filling the 1,600-person police backlog, which he would use to help increase the police presence on the streets, and signaled openness to revising restrictions on police foot pursuits, which he called a “work in progress.” He also emphasizes the need to beef up social programs to combat poverty, and fund unarmed community-violence prevention groups, though he told HuffPost that he believes he can finance those programs without raising taxes.

“There are funds available within the city budget to increase the funding,” he said. “The mayor has failed to get money out that was approved for [violence] prevention and intervention as well.”

“I also think there’s potential in rallying the downtown business community to invest more heavily,” he added. “We have a pretty generous philanthropic sector in Chicago.”

I asked García whether he planned to have a signature social or economic policy in the mold of former New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio (D), who stood up a legacy-defining universal pre-K program.

“It would be pre-K as well,” he said. “I’ve come to really appreciate how critical of an educational and socialization experience that is.”

García does not have a detailed proposal for universal pre-K, but he intends to advocate for state-level policies that would make its adoption possible. His campaign website’s “Women’s Agenda,” states, “Universal Pre-K alone would save Black families over $1.2 billion dollars annually.”

Johnson has gone on the attack against García, accusing him of “copying and pasting” Mayor Lightfoot’s public-safety plan and advancing the agenda of the city’s police union. The Cook County commissioner insists that filling the 1,600-person gap on the city police force in a short period of time is unrealistic.

“We are experiencing an explosion of violent crimes because you have politicians like Lori Lightfoot and Paul Vallas and Congressman García [who] continue to propose the same old, same old that leaves us less safe with unrealistic goals that have not delivered results,” he said in late January.

But perhaps the biggest gripe that many Chicago progressives have with García is the sense that he is deliberately seeking out a more moderate coalition of voters in the knowledge that Johnson had already carved out the progressive lane. It raises fears that he will not be as responsive to progressives once in office, according to the Chicago progressive organizer.

“If you’re going to be mayor, to whom are you going to be accountable?” asked the Chicago progressive organizer.

In these critics’ eyes, García’s gravest sin to date is his endorsement of Samie Martinez, a police union-backed candidate challenging Chicago Alderwoman Rossana Rodriguez-Sanchez, a democratic socialist.

“I am disappointed. I’ve been a longtime Chuy García supporter, and I feel like in some ways, he’s abandoned his base,” said Ramirez-Rosa, who worked on García’s 2015 mayoral campaign. “If he doesn’t make the runoff, it will be in large part because he’s turned away from the grassroots.”

Ramirez-Rosa even argued that García would be less competitive than Johnson in a runoff, noting that García’s 12-percentage-point loss to Emanuel in 2015, included a weak showing in Black neighborhoods on the South and West sides.

HuffPost asked the García campaign why he endorsed Martinez. Spokesperson Antoine Givens shared a statement he had issued on the topic previously.

“The Congressman endorsed a slate of candidates including Julia Ramirez that are also supportive of his campaign,” Givens said, noting García’s support for Ramirez, a left-wing candidate for the City Council. “When Chuy is Mayor he will find ways to work with all 50 aldermen to implement a progressive agenda which no other candidate has the ability to do.”

The consequences of defunding our schools, the consequences of defunding our mental health care services, the consequences of defunding transportation, the consequences of defunding public housing – we are experiencing the consequences of that every day.Brandon Johnson, Cook County Commissioner

Of course, the very fact that García is trying to broaden his appeal to moderate voters might mean that he is less in danger of cannibalizing would-be Johnson voters ― and vice versa.

Manuel Galvan, a marketing executive and former journalist, told HuffPost that he is deciding between Vallas and García.

“I’ve been following their careers all these years, and they’ve been pretty truthful to what they’ve been saying,” he said.

What’s more, García’s supporters maintain that his experience in Congress and in city and county government before that give him the experience needed to deliver on his promises more effectively than Johnson. They also argue that some of Johnson’s policy positions will make it harder for him than García to win the runoff election.

The most controversial of these positions is Johnson’s on-camera endorsement of “defunding” the police in 2020. He explains it as redirecting resources from law enforcement to social programs that address the root causes of crime.

As a candidate, Johnson has ruled out cuts to Chicago’s police department funding. He focuses instead on his plan to find efficiency savings that will enable the internal promotion of 200 detectives.

To gauge Johnson’s views on law enforcement more broadly, HuffPost asked Johnson whether he sees the imposition of “consequences” on law breakers, or the establishment of “deterrence” through the fear of getting caught, as concepts that are relevant to reducing crime, at least in the short term.

Although Johnson again highlighted his plan to promote detectives in his response, he declined to accept my philosophical premise, arguing again for a new approach to crime centered on reinvestment.

“The consequences of defunding our schools, the consequences of defunding our mental health care services, the consequences of defunding transportation, the consequences of defunding public housing ― we are experiencing the consequences of that every day,” he said.

When I asked García whether he thinks that Johnson’s policy proposals are too radical, either on the merits, or because of how they would make it more difficult for him to win the runoff, García declined to criticize Johnson directly.

“I have always had a pretty good sense of what working-class folks are thinking and doing in Chicago and that’s how I’ve survived,” he said. “I’ve never been the biggest sloganeer.”

Gadlin, who supported Johnson until García got into the race, is more blunt. While Gadlin supports funding non-police alternatives for violence prevention and stronger accountability for police misconduct, she sees Johnson’s endorsement of the slogan, even in the past, as a political non-starter.

“You’re not going to become mayor of the third-largest city in the country, a global city, by saying, ‘I’m going to defund the police,’” Gadlin said. “In a city where Black people are the victims of violent crime, Black women especially, defunding the police is not something that many people get behind in the city of Chicago.”

“Maybe he’ll prove me wrong” she added. “And I pray that he does.”