This doctor’s legacy includes opening the first hospital for Black people in Fort Worth

He didn’t die a wealthy man.

Although Dr. Riley Andrew Ransom Sr. accumulated substantial wealth during his lifetime, his riches were the legacy he left both personally and professionally.

During his 40-year medical career, Ransom served patients in North Texas, ran the earliest hospital for Black people in Fort Worth, operated a pharmacy, and had a major role in public health initiatives.

Ransom was born in 1886 in Columbus, Kentucky, but left to seek an education outside of the solidly segregated south. He graduated from Southern Illinois State Normal University in Carbondale, Illinois, followed by pharmacy school in Princeton, Indiana.

His medical training was done at the National Medical College in Louisville, Kentucky, an historically Black medical school. Ransom graduated as the valedictorian of his class in 1908.

Abraham Flexner’s 1910 report, which established the principles for a quality medical education and evaluated the country’s medical schools, called National Medical College, “the cleanest and best run [Black medical school] in the country.”

Because Black medical graduates were not generally admitted to post-graduate medical programs, Ransom took additional surgical training through the Laboratory of Surgical Technique at Provident Hospital (a Black hospital) in Chicago. He also undertook training at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.

Although the Mayo Clinic didn’t accept Black physicians into its training programs until 1966, Ransom may have been the first Black physician to learn there. In 1915, Ransom wrote to the Clinic asking if he could observe surgeries there (a common way for physicians to learn) during the summer. Dr. William James Mayo replied that Ransom was welcome to observe for the six week period, even though he wouldn’t receive any type of certificate. He observed a wide variety of operations by the country’s best surgeons, and Ransom’s many patients were the beneficiaries.

Ransom and his first wife, Ellen Vaughn Ransom – a teacher, moved to Brooksville, Oklahoma, in 1908. Brooksville was one of over 50 Black towns established in the state to provide a haven free from discrimination and abuse for people of color. Ransom also passed his Oklahoma state pharmacy boards, so was able to practice as both a physician and a pharmacist. Unfortunately, Ellen Ransom died following a stillbirth in 1912.

The move to Texas

Possibly because of the tragedy of losing his wife, but also for the opportunities offered by a larger community, Ransom moved to Gainesville, Texas, in 1914. Shortly thereafter he married Ethel Wilson, a nurse. Their son, Riley A. Ransom Jr., was born in 1915.

The Ransoms established the Booker T. Washington Sanitarium in Gainesville. Newspapers printed regular reports about people from the region who traveled to the hospital for surgery or treatment and gratefully mentioned the good care they received.

The couple also became involved in local activities, including patriotic events and fundraising during World War I. Ethel was a member of the Texas Commission on Interracial Cooperation, which promoted and facilitated advanced educational studies for Black people.

Building a practice in Fort Worth

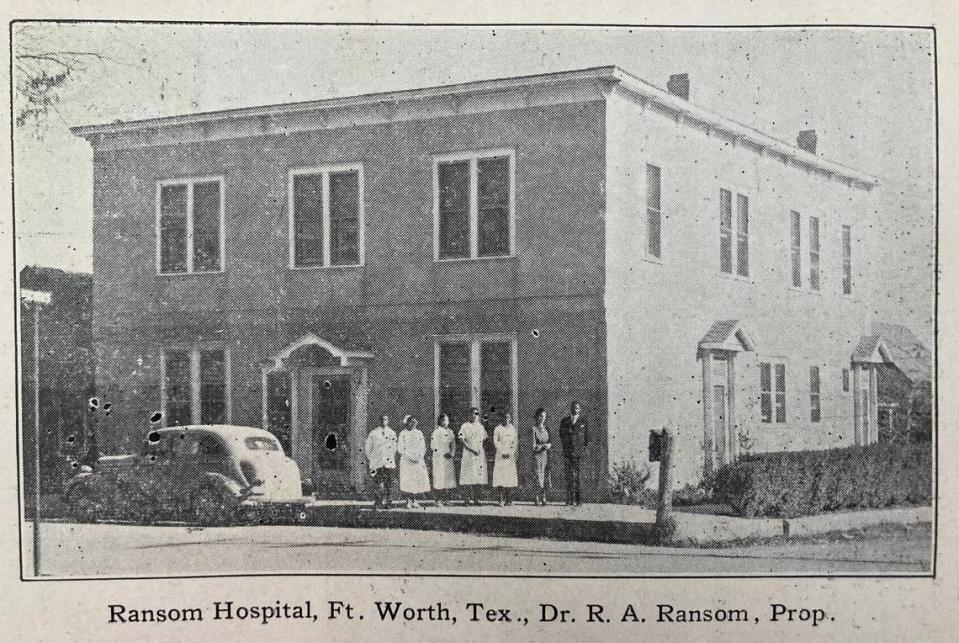

Gainesville still couldn’t provide the opportunities that a larger city like Fort Worth did. In 1920, Gainesville’s population was about 7,500 people compared to Fort Worth’s 106,482. Ethel and Riley Ransom moved their hospital to Fort Worth in April 1919, converting rooming houses (first at 417 E. Fifth and then 509 Grove) into hospitals.

Ransom favored existing rooming house buildings for hospital use. Their floor plans offered a number of rooms and were easily converted to hospital use. The nurses who worked at the hospital often lived either in one of the rooms or in the Ransoms’ own large house. Ransom also established a training program for nurses at the hospital, graduating the first class in 1924.

In 1925, Ethel Ransom, was shot in the leg a she stood on the porch of the hospital at 509 Grove St. Investigations later indicated that five shots came from the tenth floor of the Hotel Texas. Three men were arrested, but it was determined that the shots were “stray” and that “no damage” had been done.

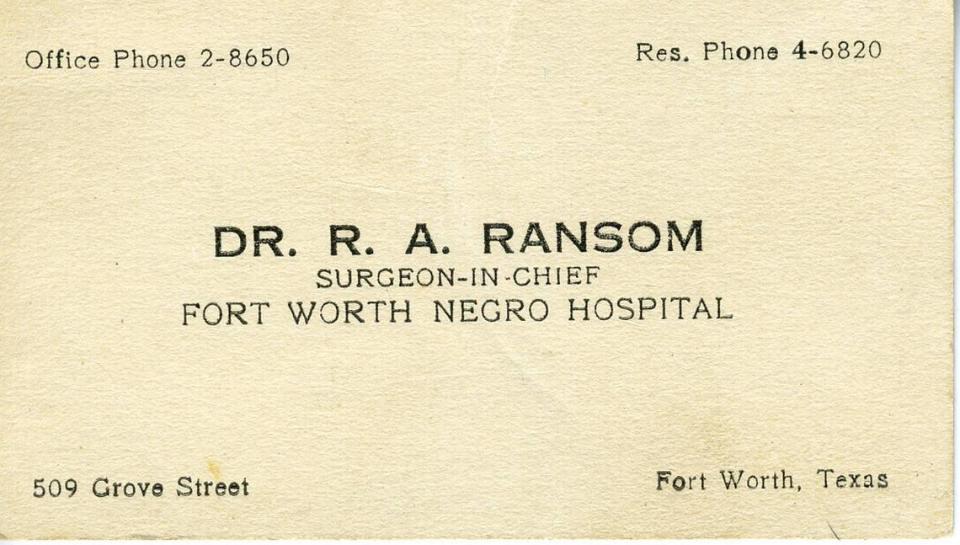

The name of the hospital shifted over time. Riley Ransom was a Baptist, so for a time it was called the Negro Baptist Hospital. About 1927, the name changed to the Fort Worth Negro Hospital. The well-known Winterthur Museum in Delaware holds a rare business card for Dr. Ransom from this time period, which notes that he is the hospital’s surgeon-in-chief.

In 1929-1930, the hospital transitioned from 509 Grove to 1200 E. First St. in a Black neighborhood in the northeast section of the central business district. The building was another rooming house with 20 rooms. Ransom developed it into a modern facility with the latest equipment.

At this time, the only other hospital facilities that would accept Black people were the City-County Hospital and St. Joseph’s. Both had “Negro wards” in the basement. Not surprisingly, many Black people preferred to have surgery or receive treatment at a hospital where they weren’t relegated to the basement, but Ransom always had to counter assumptions that white physicians were more qualified than Black physicians.

Ransom was active in the community. He served as the chairman of the social diseases committee for the Volunteer Health League of Fort Worth and Tarrant County and was a first aid instructor for the local Red Cross. He also belonged to the Tarrant County and Texas medical societies, as well as the NAACP.

Life’s challenges

Tragedy struck Ransom in December 1937, when his beloved wife Ethel died from a streptococcus infection at a time when antibiotics were not available. Shortly after Ethel Ransom’s death, her husband expanded the hospital. He added several rooms, supported by columns, on the front of the building. A new sign identified the hospital as the Ethel Ransom Memorial Hospital.

He also married for a third time, wedding Mattie B. Glover, another nurse who worked at the hospital. The couple adopted a baby in 1939, a process that required an opinion from the Texas Attorney General. The baby girl was bi-racial – and the law at that time prohibited Black people from adopting white infants and white people from adopting Black infants. Texas Attorney Gerald C. Mann ruled that because the baby had a Black father, it was Black – a continuation of the “one drop” theory.

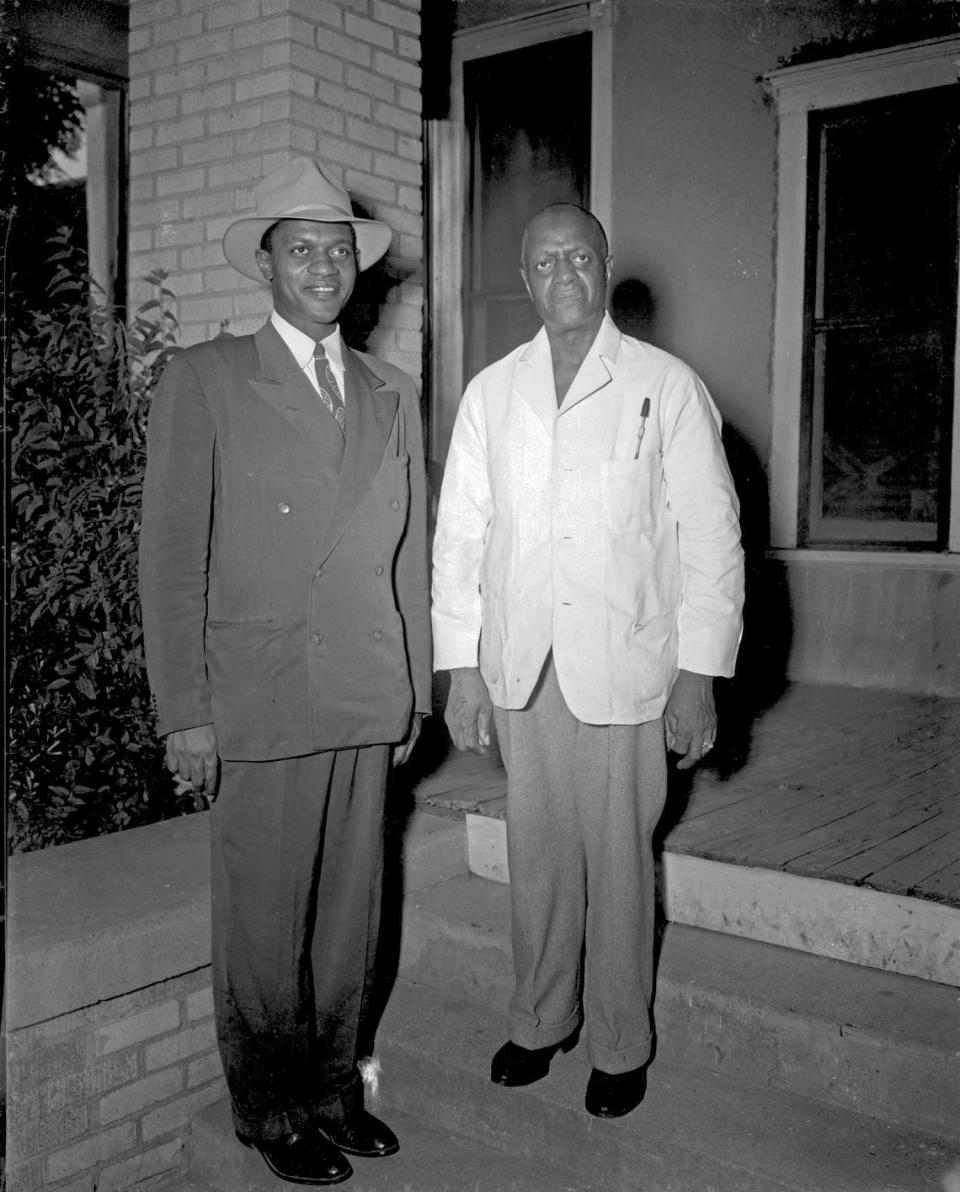

By 1940 Riley A. Ransom Jr. had completed medical school and joined his father’s practice. The hospital received a high honor that year – admission to the Register of the American Medical Society. It was the first Black hospital in Fort Worth – and one of relatively few in the country – to attain this status.

Ransom married again, about 1943, to Devalia Lee, and she adopted the daughter from his previous marriage. (How Ransom’s marriage to Glover ended is not clear.)

Ransom’s later years were dogged by his own health conditions. He had diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis (which made it difficult, if not impossible, to perform operations), kidney disease, and high blood pressure. After a 40-year career in medicine, Ransom died in 1951, leaving an estate of $10,000, or about $116,000 in 2024 dollars. His impact on the community was much larger.

Ransom has received many honors for his long service. His grave has a Texas Historical Marker, and in 2010 he was one of nine Black physicians honored with a Heritage Plaque from the Tarrant County Medical Society.

Carol Roark is an archivist, historian, and author with a special interest in architectural and photographic history who has written several books on Fort Worth history.