'We dodged a bullet': California oil spill could have decimated Huntington Beach. Why didn't it?

HUNTINGTON BEACH, Calif. – As sheets of oil washed on shore, the mayor of this surfing hub made a dire forecast: The community could be looking at an environmental disaster that could linger for years.

The reality, fortunately, appears less grim after the U.S. Coast Guard announced last week that the early October spill is estimated to be only about one-fifth of what was initially feared. Officials had reckoned up to 144,000 gallons of oil leaked into the Pacific Ocean; the new estimate is closer to 25,000 gallons.

Multiple investigations are examining everything from the cause of the spill to possible delays in reporting the accident, which may have worsened the spill. For now, officials believe an anchor from a cargo ship may have sliced open the pipeline.

From our editor to your inbox: Editor-in-chief Nicole Carroll takes you behind the scenes of the newsroom in this weekly newsletter

About a week after the oil spilled just miles from the iconic beach, it reopened to the public and its surfing crowds. The beach still remained fairly empty throughout the week, save for hundreds of orange and neon green vests that dotted the coastline: Workers cleaning up oil.

But surfers were relieved – and surprised – to see their home on the water open so quickly.

The jarring turnaround, officials and experts say, was the result of aggressive measures by government officials who learned lessons from past spills, a rapid response by environmental groups, lucky timing for some marine life, and weather conditions and currents that prevented the spill from forever changing the coastline of the Southern California beach.

How weather, ocean currents helped Huntington Beach avert disaster

The first notifications about the spill didn’t sound alarms in "Surf City USA."

Huntington Beach Mayor Kim Carr told USA TODAY she learned of a possible spill on the morning of Oct. 2, and no one seemed to be especially worried. The city’s Pacific Airshow was underway, an annual event that typically brings 1.5 million people to the tourist-dependent area.

But throughout that afternoon, Carr said, reports seemed to indicate developing concern. The U.S. Coast Guard didn’t expect oil to reach the shoreline until days later, on Oct. 4, Carr said. But boaters reported oil closing in on the city’s coast.

WATCH: How some of the most historic oil spills in U.S. history are still affecting us today

By that evening, oil was washing ashore, days before Carr said it had been predicted.

California has lost more than 91% of its historic wetlands, and some of the surviving 9% are in Huntington Beach. By late afternoon, booms – floating barriers to prevent oil from escaping – were deployed across the city to protect some of the fragile wetlands, which provide habitat for 90 species of birds and other wildlife. Carr says the move helped contain the damage to the area and its wildlife.

Another crucial element was something crews had no way of controlling: the weather and currents that changed the direction of the spill.

Southern California saw an onslaught of unusual and extreme weather events in the weeks after the spill. Large thunderstorms, widespread rain, wind gusts up to 50 mph and 11-foot waves struck the bottom half of the state the week after the spill, said NOAA senior meteorologist Alex Tardy.

The conditions not only made it hard for meteorologists to estimate how much oil leaked into the ocean, Tardy said, but could have influenced the path of the spill.

“Oil moves with the ocean current and ocean waves,” he said. “With thunderstorms, heavy rain and gusty winds, you’re probably going to disrupt it.”

Oil spill sends dead birds, fish onto California beaches: This map shows how big it really is

But then came sunny weather and calm skies. Ocean currents, invisible to the human eye but constantly moving, along with the strong winds had pushed much of the oil south toward San Diego and away from Huntington Beach.

While oil concentrated in one area can be easier to clean up, it can suffocate wildlife and the ecosystem.

“By being proactive, getting a little bit lucky with the weather ... we dodged a bullet,” Carr said.

California oil spill could have been 'a whole lot worse' for wildlife

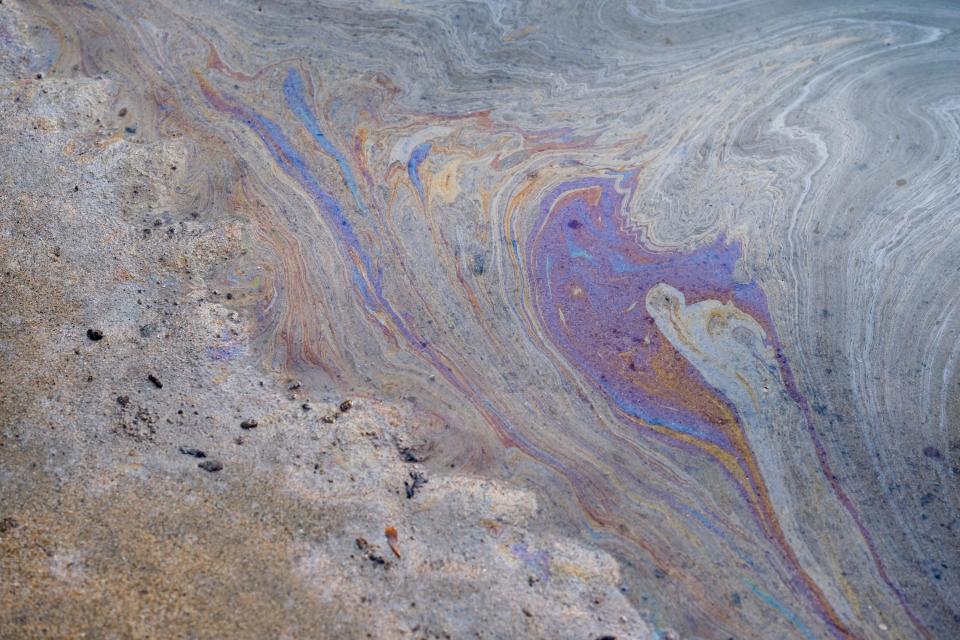

As beachgoers and surfers were welcomed back to Huntington Beach, the damage below the water and sand were still unclear. Oil continues to wash ashore, and tides coming in and out are mixed with chunks of tar.

Oil spills have historically hurt marine life and underwater ecosystems, reducing populations of sea creatures and decimating smaller life forms like plankton. They can harm coral reefs, which can have a ripple effect on the larger ecosystem.

The animal most people see affected first are sea birds. The Oiled Wildlife Care Network, a statewide agency that cares for wildlife after oil spills, said 77 oiled birds had been recovered. Of those, 47 died. Eleven fish were found dead from the oil.

“This could have been a whole lot worse,” said wildlife veterinarian Ole Alcumbrac, noting the time of year probably helped reduce the toll.

“The birds, specifically, really lucked out because it was after the nesting season and before migration along the Pacific Flyway started, so there could have been a lot more birds in the area, or birds that were vulnerable because they were still nesting."

The damage under the water will take time and a “crystal ball to predict," Alcumbrac said. Some animals probably swam through the pollution and may have ingested toxins, which can pose long-term side effects. Many were displaced by the oil and would be searching for new homes.

Cultural, economic affects remain mostly invisible along California coast

Huntington Beach was notably empty on a sunny afternoon last week. Dozens of bikers and joggers cruised along the bike path, but few ventured onto the sand.

Russ Jones, 64, was one of the only surfers out. He has lived in Huntington Beach for 40 years, and he surfs at least twice a week. The swell was good on this day, he said.

Jones was around for Huntington Beach’s 1990 oil spill, which leaked more than 400,000 gallons of crude oil into the Pacific Ocean, and he feared the same disaster 30 years later. But the October spill is projected to have leaked much less oil than the 1990 spill and much less than originally feared.

Jones was surprised the beach opened again so quickly, but he was happy nonetheless.

“Surfing is a huge part of my life,” he said. “So when they shut down something like that, it really affects you mentally and physically, because it’s therapeutic and it’s exercise. It clears your head.”

Cultural and economic harm may be the biggest, yet most invisible, result of the spill.

Opinion: Latest California oil spill paints grim picture for future generations

California’s Department of Fish and Wildlife shut down all fisheries in the area on Oct. 4, and they remained closed as of Thursday. Southern California also has a large community of shore-based fishers – people who fish from the beach, jetties and piers, said California State University Channel Islands environmental science professor Sean Anderson.

“Those shore-based fishing communities tend to be dominated by first-generation immigrants, a majority from Southeast Asia,” Anderson said.

Fisheries will suffer economic damage, as well as the businesses that line the Huntington Beach coastline, which already have been battered by the pandemic. Then there are people on the shore who aren't just fishing for money – they’re fishing for dinner.

Until the spill is cleared, the effect on their way of life will remain very real.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Huntington Beach oil spill could have been a disaster for 'Surf City'.