Does anyone roast chestnuts on an open fire? | ECOVIEWS

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Q. Singers as disparate as Nat King Cole, Bing Crosby, Justin Bieber and John Legend have recorded "The Christmas Song" (with the opening line “Chestnuts roasting on an open fire.") Were roasted chestnuts really a thing? I thought chestnut trees were extinct.

A. The original American chestnut tree is “functionally extinct” according to “The American Chestnut: An Environmental History” by Donald Edward Davis (University of Georgia Press, 2021). The main culprit, chestnut blight, was identified by a USDA botanist in the early 1900s when all of the American chestnut trees around the Bronx Zoo died. He concluded that the fungus had spread from imported Japanese chestnut trees, which can carry the disease but are immune to its effects.

More: How did the screech owl get its name? | ECOVIEWS

In the most thorough book yet written on chestnuts, the author covers the evolutionary history of the nine species living today from their ancestors 90 million years ago through the 20th century when an estimated 5 billion American chestnut trees died.

The pervasiveness of the tree in eastern U.S. culture is evident not just in that popular holiday song but also in Longfellow’s much-recited poem “The Village Blacksmith.” Published in 1840, it begins “under a spreading chestnut-tree.” In 1872, vendors in New York sold roasted chestnuts on all of the main streets around Broadway. A popular 1884 cookbook gave recipes for chestnut gravy, chestnut stuffing and chestnut croquettes. By 1906, railroad companies had timbered enough American chestnut trees to make more than 1 billion crossties.

A 1911 map shows the range of chestnut trees from Maine to northern Alabama and Mississippi, with the blight still concentrated in the northeast. By then nearly all chestnut trees in New York City were dead.

The chestnut blight spread rapidly into New England and south through the Appalachians. In 1921, only one street-vending chestnut roaster could be found in Bridgeport, Connecticut, which, like Boston and New York, had once had dozens selling roasted chestnuts on busy street corners.

One county in Virginia that “had a decade earlier produced tens of thousands of bushels” had virtually no nut-bearing trees by 1928.

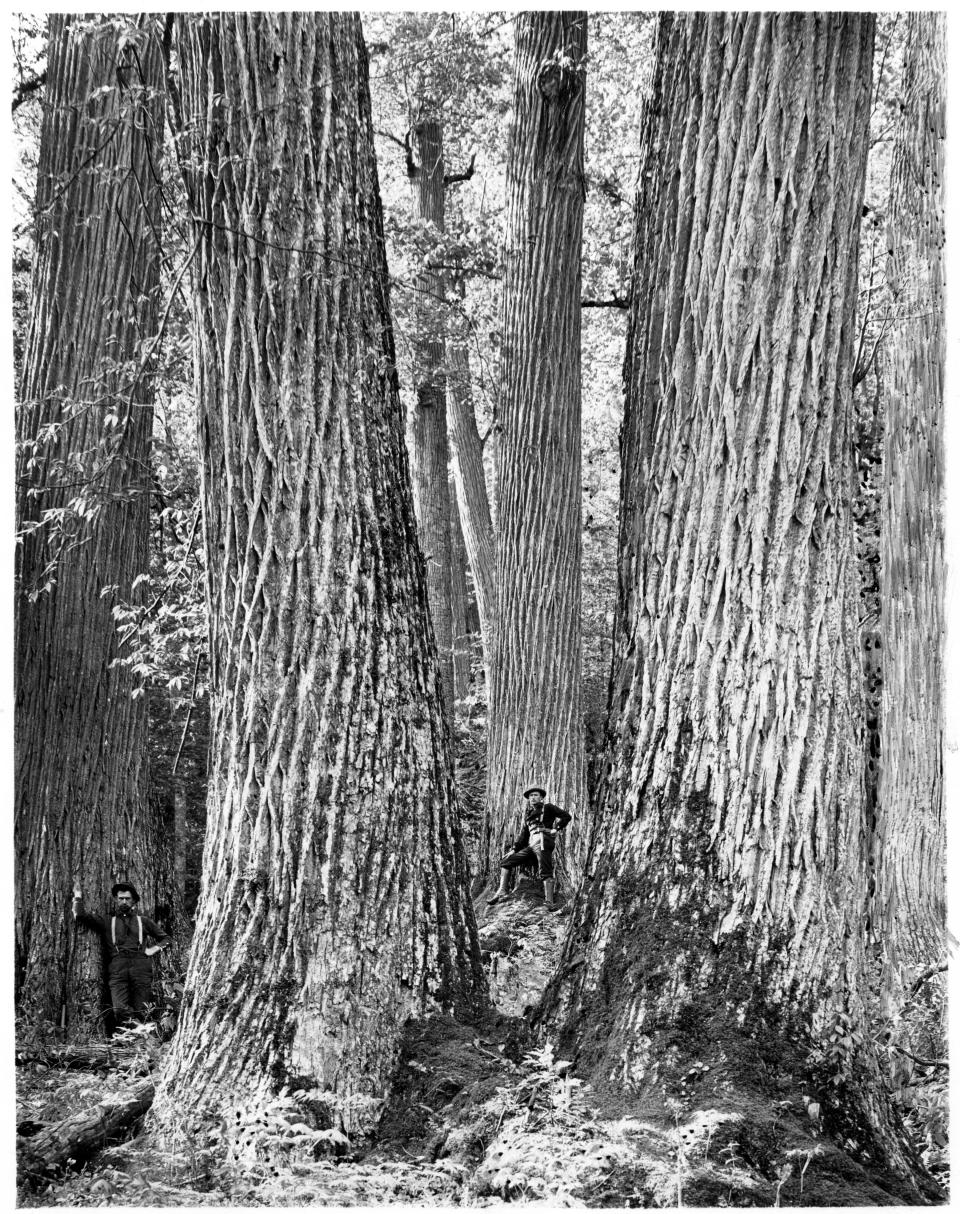

The lives of the Cherokee people and other inhabitants of the Appalachian Mountains were permanently altered by the disappearance of immense forests once dominated by chestnut trees. The nuts and wood products of the trees were vital to economies of numerous communities. In 1942 the American Forestry Association (now American Forests) reported the largest known native chestnut tree — 9 feet in diameter — in the Great Smoky Mountains. By 1950, the tree was dead.

Chestnut trees thrived in North America in part because of various animals’ seed-burying habits, a major source of new seedlings. Henry David Thoreau reported finding a cache of 35 chestnuts deposited by a meadow mouse. Crows, chipmunks and squirrels buried the overabundance of nutritious chestnuts in the ground for later consumption.

Blue jays are credited with being one of the primary animals to assist in the spread of chestnut trees because they could carry several seeds at a time in their esophagus. Another disperser of American chestnuts was probably the passenger pigeon, which went extinct before the blight had wiped out the trees themselves. Birds and mammals continue the vital ecological process of seed dispersal today.

Future generations will never again see vast forests of giant American chestnut trees, even if the blight fungus were to be eradicated. But hope exists that people might once again enjoy the sweet scent of an American chestnut tree’s flowers in the spring and the aroma of roasting chestnuts in the fall.

In isolated areas of the country a few trees live seemingly untouched by the blight. Hybrid crosses with chestnuts from other parts of the world as well as genetic modifications of the few existing American chestnut trees could lead to trees less susceptible to chestnut blight. In the meantime, we’ll just have to appreciate them in holiday songs and old poems.

Whit Gibbons is professor of zoology and senior biologist at the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory. If you have an environmental question or comment, email ecoviews@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on The Tuscaloosa News: Does anyone roast chestnuts on an open fire? | ECOVIEWS