Does development in York County always have to come with a loss of quality of life?

(Another in a series of occasional columns about York County and its relationship with the Mason-Dixon Line.)

When people on social media call for saving landmarks or popular green spaces, some people hop in to disagree.

Who are you to tell an owner what to do with his property? they ask. It’s simply the property owner’s decision.

“Any of the complainers on here should put up their own money to buy this house,” one commenter said on a Retro York Facebook post about saving the Rutter’s-owned Hoke House in Spring Grove, “and quit trying to spend Rutter’s money.”

There’s evidence that this owner-is-king thinking has been particularly strong in York County, and municipal officials and developers have dialed into it, past and present.

In recent years, those favoring preservation had to fight hard to save the Mifflin House in Hellam Township, even with its Underground Railroad and Civil War pedigree. But then came the proposed demolition of the 1750-era Hoke House. Then plans were proposed for a warehouse on green space in a congested area near Prospect Hill Cemetery in Manchester Township. And the beat goes on.

Fortunately, the voices for preservation are growing louder as green space shrinks and treasured buildings come down.

The modern preservation movement is relatively young in an old county, starting with York’s Golden Plough Tavern restoration in 1964. The saving of First Presbyterian Church’s Billmeyer House a decade later was another early win.

But look what came down around them in the 1950s through 1970s in York, mostly in the name of parking: the Children’s Home of York, Faith Presbyterian Church, City Market, York Collegiate Institute and the Springdale Mansion. The latter, once proclaimed one of the finest mansions in the state, was demolished, in part, “because children ran in and out of it.”

So where does this impulse that “he who owns the land is sovereign” come from?

Part of that can be traced from south of the border.

County distrusts government

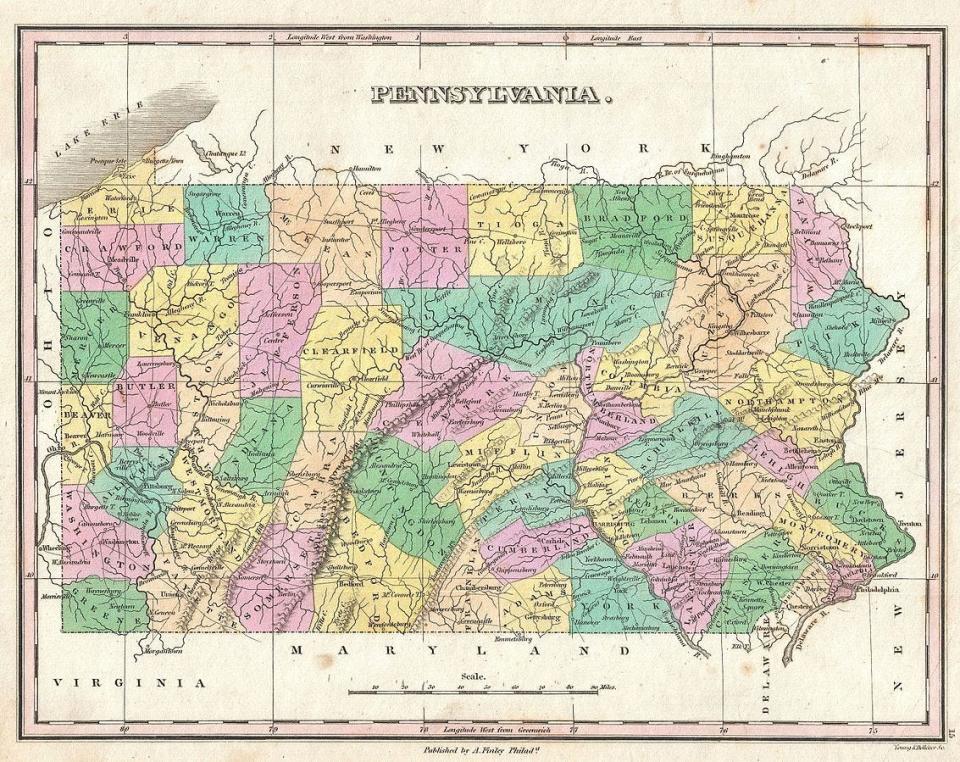

By border, we mean the Mason-Dixon Line, an invisible 1760s surveyor’s line marked by milestones that has long served as a major influence on York County.

The county shares a long border with the South, a 65-mile line with Maryland or about 28% of the original line. And then it measured a lengthy 40 miles after Adams County separated from York County in 1800.

A decade after the famed British surveying team ran that line, York County residents took in the quest for American freedom firsthand, as hosts of the Continental Congress in 1777-78. They looked on as Congress adopted the Articles of Confederation, America’s first constitution, a decidedly states’-rights document. This fear of strong government came in the American Revolution era when patriots were fighting against the tyranny of King George.

The U.S. Constitution attempted to fix the flaws in the Articles. As statesman Robert Morris said, the Articles conferred the federal government the privilege of asking for everything, but it gave each state the prerogative of granting nothing.

Still, York County initially went along with the Federalists of strong central government fame, perhaps liking another George — as in George Washington — as much as many detested King George. And the county separated from Lancaster in the first place because it needed government — a sheriff and courts — to take a bite out of crime.

But acts viewed as strong-handed in the 1790s — the Whiskey Tax, for example — influenced voting patterns away from the Federalists toward the states’ rights party: the Democrats. The Democrats embraced the politics of the South, the views of Southerners and landowners Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson.

The suspicion of government swept across York County with the Southern winds, including when those in power dealt with private land. So you take a centralized authority — say York County’s government — and you carve it up into 35 townships and 36 boroughs so the splintered public sector lacks resources to influence much.

Since those days, most county residents backed the Jeffersonian idea of the best government is one that governs least.

York County voted with the Democrats, the party that best reflected the South throughout the 1800s. And when the Republicans became associated with smaller government in the 1980s, York County crossed over from a Democratic majority in voter registration to Republican. And Republicans remain in the lead by a 161,662-99,218 margin today.

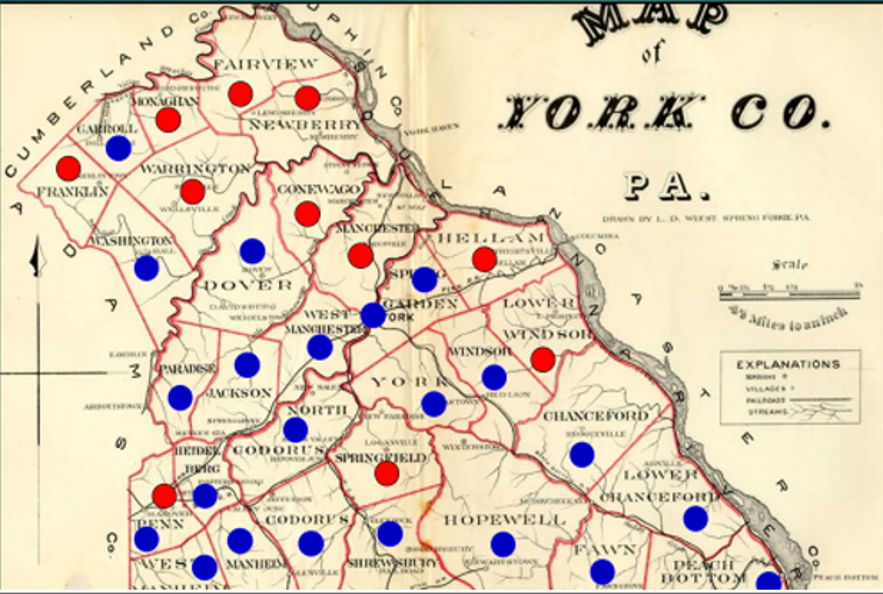

Here’s another piece of evidence about how the South influenced York County: In 1860 and other presidential elections, the closer townships were positioned to the Mason-Dixon Line, the stronger their Democratic vote. Precincts in the Quaker stronghold in northern York County largely voted Republican. In the end, York County voted against Abraham Lincoln in 1860 and 1864.

Historic courthouse demolished

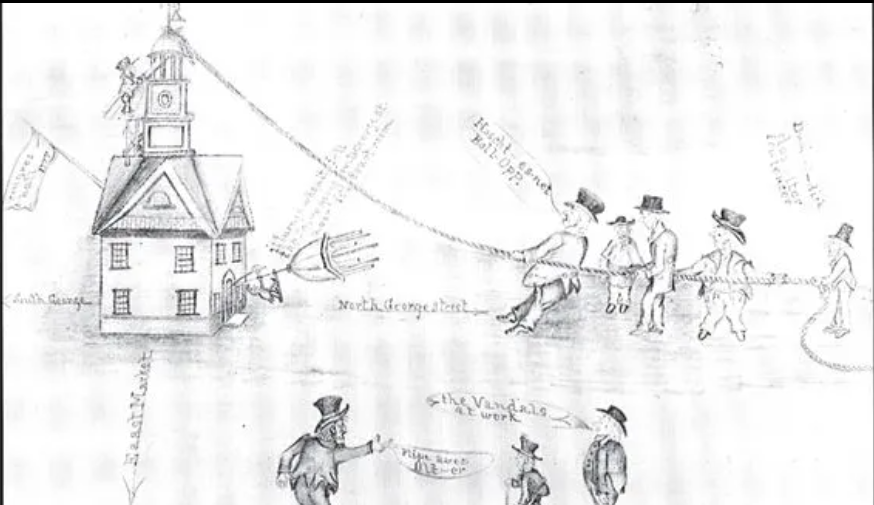

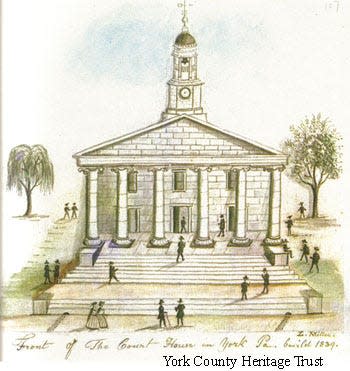

Another indicator of how York County residents viewed government came about 1840 when county and court operations moved from Centre Square to the location of today’s York County Administrative Center, the old East Market Street courthouse.

Instead of leaving the now-vacant Colonial-era courthouse standing — the place where Continental Congress framed America’s first constitution — workers roped the cupola, toppled it and then demolished the rest of the brick structure.

This was not a move to clear the square of obstructions. Market house operations continued there; the business of York County was then farming.

York County showed its low regard for government by shuffling its seat from the center of things up the street and to the right.

And people noticed. One observer said not one brick would be touched, if it were up to him.

There will be a day, he rightly predicted, that pilgrimages would be made to buildings connected to the “toils and triumphs of the Revolution — that they would become the Meccas of Freedom, where her sons would congregate to rekindle in their bosoms the sacred flame of gratitude to the deliverers of their country and of devotion to those principles which they had defended.”

With the courthouse demolished, York County lost more than those pilgrims. It showed firsthand its low view of government.

Market sheds pulled down

About 50 years later, it was the two Centre Square market sheds’ time to go. York, amidst the Industrial Revolution, needed to move trolley-bound workers to those red brick factories through the square. And the stuff made in those factories needed to pass through there, too.

The business of York County was no longer agriculture.

Workers, under the cover of darkness, lassoed market shed supports with ropes and pulled them down. No courts, representing the strong arm of government, convened to stop the demolition team in the middle of the night.

In 1898, the county built the Dempwolf-designed courthouse atop its demolished predecessor. That ornate building, now the York County Administrative Center, met its own challenge in the early 1950s. It was almost demolished to make way for a building of modern design. Fortunately, it survived, expanded with wings and hosted court until the early 2000s when the York County Judicial Center replaced it to accommodate a growing judicial system.

So, if you’re keeping score: four courthouses since the 1750s, two demolished, one threatened and then expanded and the new judicial center whose design has generously been called bland.

County’s business is business

The demolished market sheds signaled that the business of York County is business — not agriculture, not government — to this day.

About a century after the downing of the market sheds — the triumph of industrialization vs. agrarianism — county land was used for purposes other than farming for the first time.

In 1976, 57% of the county’s land was in use for farming. In 1987, 47% was in agricultural use. The “break-even” year, thus, comes about 1983.

Indeed, about the time all those York city landmarks were coming down to provide parking — 1960 to 1992 — the county lost about 30% of its farmland to suburban sprawl, in part to feed the automobile culture.

In the 20 years before 1996, as much land was built over as occurred in the previous 200 years.

That hasn’t stopped. U.S. Department of Agriculture numbers show that York County lost 14% of its land in farming between 2005 and 2017.

York’s location on the Mason-Dixon Line again has contributed to this. The county and its long border sits on a spot where North meets South and serves as a major entry point to the Keystone State, connecting the Northeast and Southeast.

This makes York County a magnet to warehouses and other logistics development. And a winsome draw for people — at least for now — with population growth in the past decade measuring about 5%.

Lancaster’s links to York

It’s always insightful to look toward Lancaster, York County’s parent, as a comparison point. As York County sprawled 65 miles — and then 40 miles — along the Mason-Dixon Line and looked South, Lancaster County’s footprint on the line was a mere 6 miles, and it leaned toward Philadelphia.

Clearly, Lancaster has its own struggles with development. Its land in farms decreased by 7% from 2007 to 2017, half as much as York County.

But three points from this land east of the Susquehanna give insight into questions of land-use and the sovereignty of private ownership.

First, an outward sign of support for preservation in Lancaster County comes with its treasured covered bridges. The county touts these scenic relics of the past, numbered at 25.

Interestingly, York County hosted 25 covered bridges in 1937. Today, it shares a relocated covered bridge with Cumberland County on Messiah University’s campus. That’s it.

The Amish have provided a second asset for preservation in Lancaster County, with their tendency to keep land within families instead of readily succumbing to development pressures. Interestingly, in the past 25 years, the Amish have been moving across the Norman Wood Bridge in southeastern York County from Lancaster. They have been progressively moving west across southern York County, with the intent to keep land in farming. This is one of York County’s greatest hopes for land preservation.

And at least two organizations with Lancaster County ties have been effective on the preservation front in York County: Lancaster Conservancy and Susquehanna National Heritage Region.

The conservancy has secured river land and hills north and south of Wrightsville. Susquehanna Heritage led the difficult battle to preserve land that later became Highpoint and Native Lands county parks and served as a major player in efforts to preserve the Mifflin House.

Fortunately, there are other chapters to York County’s preservation story. Farm and Natural Lands Trust has preserved about 14,000 acres in York County. It tends to focus on open space preservation, and the York County Agricultural Land Preservation Board preserves active productive farmland.

And the York County Economic Alliance is pushing outdoors and cultural assets as economic drivers.

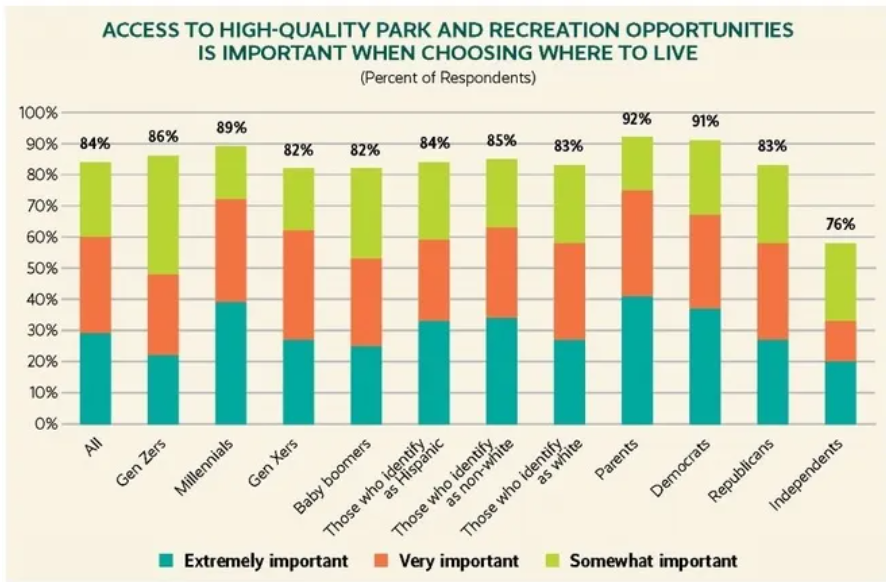

Talented people, recruited to work in York County, increasingly care about green space and other quality- of-life factors. Corporate executives are trending that way, too.

“Talent attraction will be the competitive issue of the next decade,” the Economic Alliance’s Silas Chamberlin has written. “Regions that offer high-quality of life, access to open space and walkable, historic communities will succeed.”

If outdoors and cultural assets are to be part of the business of York County, government officials must improve in fostering smart growth instead of the hodgepodge in place now caused by a history of landowner sovereignty.

Jacob Bixler had a cow

All that said, it has been — and will be — an uphill fight to slow the apparent quest of developers to build on every acre of York County.

The winds of individualism instilled in county residents from the South are among the powerful forces against preservation. Perhaps Jacob Bixler’s cow provides one more example from history of what preservationists are up against.

The cow caused an insurrection in 1786 in those early republic years in which a nation was forming after gaining independence.

A tax collector detained Bixler’s cow because the Manchester Township animal’s owner refused to pay an excise — an example of aversion to government.

On the day the cow was up for tax sale, a group of 100 armed men marched into York from Manchester ready to make “rough music,” as a history says.

York’s townsmen assembled to meet the rioters with weapons of their own. If they must pay taxes, that bunch from Manchester would, too.

The two sides clashed and after some “boxing and striking,” the invaders soon dispersed. They later appeared before the court and paid fines.

For once, government — the court — would win in this moment history remembers as a “cow-insurrection.” For a day, the business of York County was government.

As it must be again in a way that fosters smart growth, to fend off an all-out assault by developers against green space and our landmarks.

This must happen because, as a commenter about the Hoke House said: “Eventually there won’t be any history left to save.”

Sources: James McClure’s “Never to be Forgotten,” U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture, 2020 U.S. Census, Carter and Glossbrenner’s “History of York County, Pa.,” YDR files, June Burk Lloyd’s Universal York blog.

Jim McClure is a retired editor of the York Daily Record and has authored or co-authored nine books on York County history. Reach him at jimmcclure21@outlook.com.

This article originally appeared on York Daily Record: The business of York County has long been business. But at what cost?