What does the end of Title 42 expulsions mean for Black migrants?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

“Even though it was implemented under the guise of a public health issue, it was very clear from the start that this was a plan to keep Black and brown people out of the U.S.” — Haddy Gassama of The UndocuBlack Network.

After years of condemning Title 42, which allowed border officials to legally remove migrants seeking asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border during the COVID-19 pandemic, advocates for Black migrants are far from celebrating the end of the public health emergency policy.

“It should be a major victory celebrating the end of Title 42,” Guerline Jozef, executive director of Haitian Bridge Alliance, told theGrio. “Unfortunately, the end of Title 42 is also connected to a lot of new policies that can make it impossible for people to still be able to have access to protection [and] to have access to ask for asylum.”

Title 42 expulsions

While the law has been on the books since 1944, Title 42 was not enforced to stave off migration until the Trump administration. Then-President Donald Trump adviser Stephen Miller began using the legal provision to expel migrants at the border back to Mexico.

Despite scientists at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention arguing that the policy had “no valid public health reason to issue it,” the Trump administration began enforcing the law in March 2022.

Advocates, who previously called Trump’s immigration policies racist, were critical of Title 42 and how it made seeking asylum more difficult for Haitian and African migrants facing violence and instability in their native countries.

Haddy Gassama, national policy and advocacy director at The UndocuBlack Network, said Trump’s enforcement of Title 42 was “rooted in anti-Blackness and white supremacy” and was the “brainchild” of Miller, whom she characterized as a white supremacist.

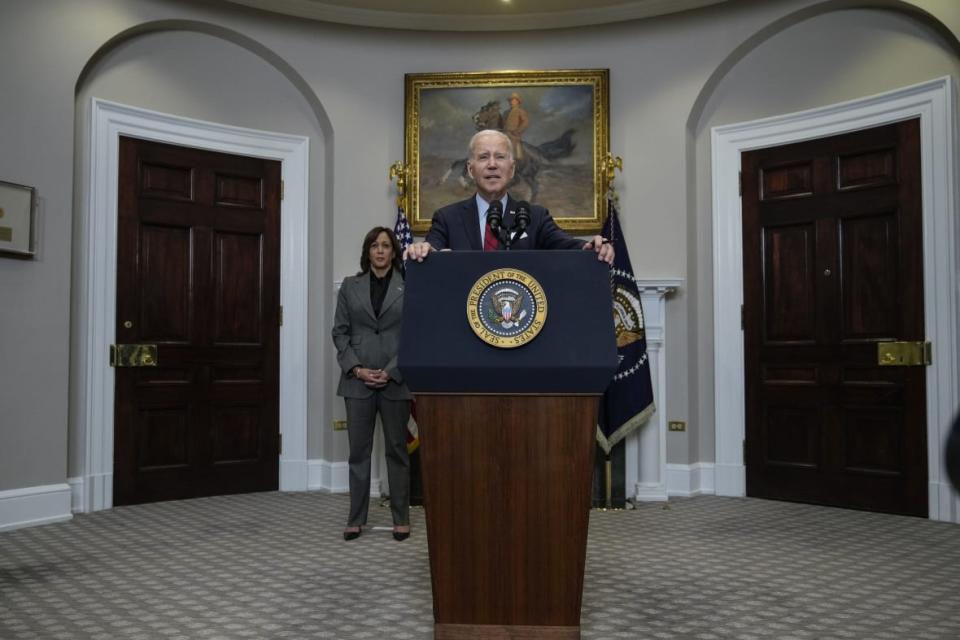

When President Joe Biden took office, advocates took issue with the Biden-Harris administration continuing to enforce Title 42 at the border.

“Even though it was implemented under the guise of a public health issue, it was very clear from the start that this was a plan to keep Black and brown people out of the U.S.,” said Gassama. “It took over a year of advocacy just to get the Biden administration to stop doubling down on this Trump-era policy.”

After a slew of court battles over the legality of Title 42, the Biden-Harris administration moved to lift the ban once the federal government ended its COVID-19 public health emergency on May 11.

What is Title 8 immigration?

Now that Title 42 has come to an end, the federal government is now moving toward the enforcement of Title 8, a set of statutes that allow for expedited deportations of migrants.

In January, the Biden-Harris administration announced a number of new border enforcement policies, including requiring migrants to seek asylum in Mexico or another country before seeking it in the U.S. and requiring they set appointments via a mobile app to begin their asylum process instead of showing up at the border.

Advocates say these new migrant policies are simply a continuation of Title 42.

“We cannot celebrate the end of Title 42 because that end is connected to so many hardline policies that are rooted in deterrence … to make sure people don’t actually ever make it to the United States,” said Jozef of Haitian Bridge Alliance.

Gassama said while the latest actions from the Biden-Harris administration are “tied with a nice bow of better policy language or now softer diplomatic language … it aims at the same goal of keeping people out instead of welcoming people humanely in a dignified manner.”

Immigration advocates argue that the Biden administration’s new deterrence policies will disproportionately impact Black migrants from Haiti and sub-Saharan Africa, who face racial discrimination and violence in other countries during their route to the United States.

Black migrants, said Gassama of The UndocuBlack Network, have a “hard enough time as it is just traversing Latin American countries that also have their own issues around anti-Blackness and white supremacist notions.

“To expect for someone coming from a sub-Saharan African country fleeing a number of different harms to try to apply for asylum or refugee status in Panama or Mexico or wherever is preposterous,” she argued. “People are literally losing their lives or being extorted by cartels or sexually assaulted just because they’re Black in these countries.”

As thousands continue to seek asylum at the border, the Biden-Harris administration has repeatedly argued that it is using the tools that are available in the absence of immigration legislation from Congress that would provide more funding to hire more border patrol officers to process migrants.

As an alternative, the administration announced last week that the Department of Defense is sending 1,500 troops to the U.S.-Mexico border. Biden officials made it clear that military personnel would not be there to enforce the law but to assist border patrol with administrative tasks like data entry and warehouse support.

Advocates argue that any surges occurring at the border are a direct result of deterrent border policies and not necessarily a lack of border personnel or resources.

“If, from the beginning, they took steps to actually center policies into reestablishing ways for people to get access to protection, they would not have to deal with this bottleneck right now,” said Jozef.

Gassama argued that the use of troops at the border is “code for helping quickly process deportations,” rather than “dealing with asylum seekers and asylum cases and having them there in good faith to help process the so-called surge of migrants that they’re expecting.

“What that shows is that this is a deliberate choice that the Biden administration is doing,” she said, adding that the White House is taking its “lead from whatever Republican talking points for that week are as it relates to the border.”

She continued, “Because Republicans are so good at dog whistles … the administration is going to kind of be beholden to always being on the defensive, always wanting to seem like they’re not soft on immigration.”

While the Biden-Harris administration is deterring migrants from showing up to the border at will, it also expanded its parole programs to allow up to 30,000 migrants per month from Haiti, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Cuba. Eligible migrants, who can remain in the U.S. for up to two years, must have a sponsor and pass vetting and background checks.

Advocates welcome the expanded migrant parole programs. However, they do not see them as a trade-off for the administration’s other policies, like banning migrants from reentry for five years under Title 8 if they do not meet certain asylum requirements.

“They take one tiny step forward, but they anchor it to these really harsh, very clear deterrence measures,” said Gassama.

As the Biden-Harris administration moves away from Title 42 and enters the new era of Title 8, advocates say they will continue to assist as many migrants as they can and closely monitor processing on the ground.

A delegation of immigration advocacy leaders from several organizations, including Haitian Bridge Alliance and The UndocuBlack Network, will be at the border Thursday and Friday to observe and provide humanitarian aid to migrants.

“We are on the ground at every port of entry right now, from Reynosa and Matamoros to El Paso to Tijuana, to bear witness to what is happening at the border,” said Jozef. “And to make sure we hold everyone involved accountable.”

Gerren Keith Gaynor is a White House Correspondent and the Managing Editor of Politics at theGrio. He is based in Washington, D.C.

TheGrio is FREE on your TV via Apple TV, Amazon Fire, Roku and Android TV. Also, please download theGrio mobile apps today!

The post What does the end of Title 42 expulsions mean for Black migrants? appeared first on TheGrio.