'Does it have to be your kid?' Family calls out mental health system after teen's suicide

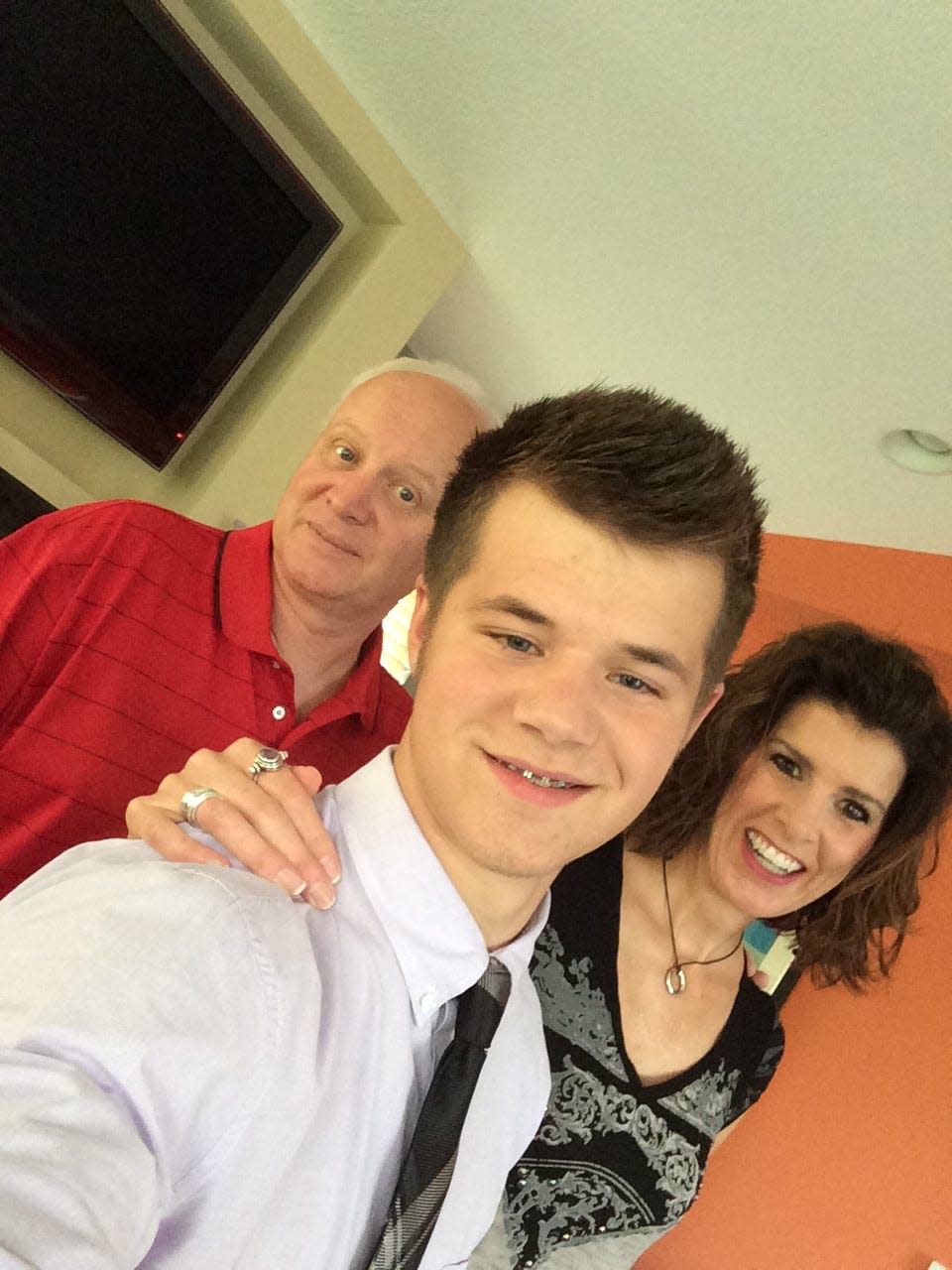

To those who loved him, Aiden Hofer Phelan-Ruden was a bright young man with an insatiable curiosity.

The teenager, who lived in rural northeast Polk County, began asking questions as soon as he could talk, and never stopped, his family said. He always wanted to know more, meeting each answer with an ever more complex and interesting question.

Aiden brought that curiosity to the classroom, but teachers said he had a fun side as well. He made other students laugh, and family members said he was someone who "loved being a kid."

“He had so much joy in his body, and so much pain too,” said Laurie Phelan, his great-aunt.

Aiden struggled with depression and anxiety. On Oct. 1, he died by suicide. He was 15.

His family tried to get Aiden the help he needed, but instead, they said, they faced roadblock after roadblock in Iowa's underfunded and under-resourced mental health system for children. That system is under greater strain in the wake of the pandemic as more children struggle with mental illness, experts say.

To Aiden's family, the problem wasn't just the lack of acute psychiatric beds or the shortage of mental health care staff.

It was also the lack of resources for school districts, which typically have no certified behavioral specialists on staff. And it was the lack of programs that can help uplift children most at risk.

In a moving obituary published online last week, family members wrote that they believe Aiden's life was cut short "by ambivalence, powerlessness and lack of collective capacity and will to improve the lives of our most precious resources — our children."

"How many more kids die before we say, ‘This is a problem’?" Laurie Phelan told the Des Moines Register. "One more? Five more? Does it have to be your kid?"

More on mental health:Here's how to tell if someone has an eating disorder. And how to get them help

Aiden struggled with bullying, father figure's death

Aiden was raised near Farrar, on a farm that had been in the family for more than 120 years.

He and his older brother, Brock, were born to parents who struggled with substance abuse and were taken in by his grandparents, Teri Phelan-Ruden and Jeff Ruden. To the boys, they were mom and dad ― or as they called them, Pi and Papa.

Later in life, Aiden was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, social anxiety disorder and depression. Laurie Phelan said he took medication to help alleviate some of his symptoms, but it didn't always work.

When he was a freshman at Bondurant-Farrar High School, Aiden was bullied in school, so much that his grandparents went to the school with their concerns. He received hateful messages through Snapchat and other messaging apps and was beaten up several times, they said.

“He used to be so scared that he would eat his lunch in the bathroom. It was that bad,” Laurie said.

Family members said he continued to receive vile messages through social media even after his death.

The Bondurant-Farrar Community School District did not respond to a request for comment.

As the bullying continued, Aiden began locking himself in his room and refusing to go to school.

Then, Jeff Ruden, his grandfather and the only father figure he had known, died suddenly in March at the age of 56. Aiden fell deeper into depression.

Aiden attempted suicide at least once before in the past year. He stayed overnight at the pediatric psychiatric ward at Iowa Lutheran Hospital in Des Moines and continued to go to counseling in the weeks that followed.

His grandmother, Teri Phelan-Ruden, spoke with Aiden often and begged the teenager to tell her if he was ever in such pain that he was having suicidal thoughts, Laurie Phelan said. Aiden promised his grandmother he would go to her if he needed help.

Teri Phelan-Ruden feared that these conversations and Aiden's hour-long therapy appointments were not enough. He needed more care, she believed.

She desperately tried to get Aiden into a Des Moines-based residential treatment program but was told it was at least a six-month wait for a bed. Phelan-Ruden declined to speak for this story.

Aiden never got the help he needed.

“We lost him in that time,” said Franci Phelan, his great-aunt.

More on mental health:Navy veteran promoting suicide prevention, troops helping out are welcome military presence on RAGBRAI

Polk County sees spike in youth suicides over past two years

Polk County has seen an increase in youth suicides over the past two years, a pattern connected to the rising rates of depression and anxiety among children in Iowa and across the U.S. following two years of the pandemic, Polk County Medical Examiner Josh Akers said.

So far in 2022, six juveniles have killed themselves. Last year, there were five.

By comparison, the county recorded two youth suicides in 2020 and three in 2019.

"I think that we as a nation are in the midst of a mental health crisis, and that’s being manifested as suicides and overdoses," Akers said.

The 2021 Iowa Youth Survey showed almost one in four — or 24% — of 11th graders had thought about suicide in the past year. Forty-nine percent of students who indicated they thought about ending their lives went so far as to make a plan, the survey reports.

Earlier this year, the CDC reported about 44% of children nationwide experienced persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness. Nearly 20% had seriously considered attempting suicide, and 9% had actually attempted suicide.

And like Aiden's family, some Iowans are finding there are limited resources to meet the growing demand.

According to a survey from Kaiser Family Foundation, about 40% of respondents in Iowa had difficulty obtaining mental health care for children ages 3 to 17. That's on track with the national average, with 43% facing some level of difficulty in obtaining services.

Iowa has one of the nation's lowest rates of child and adolescent psychologists per 100,000 residents younger than 18, according to a 2020 report from the Behavioral Health Workforce Research Center at the University of Michigan.

The majority of Iowa's 99 counties lack a child psychiatrist, according to the CDC.

It's estimated half the children in the United States who have a mental health disorder don't receive the treatment they need — a factor exacerbated by workforce shortages and increased behavioral health needs.

"There are lots of Aidens all over this country — some of them we know about, and some we don’t," said Daniel Phelan, Aiden's great-uncle. "We’ve got a system which is ill prepared to be able to deal with mental health issues in this country, and unfortunately, the de facto mental health care facilities become local school districts, they become hospitals, they become police officers.

"None of them are really qualified to do this work."

More:National three-digit suicide and mental health crisis hotline 988 begins July 16

Aiden's relatives say there's not enough support around families

The need for greater access to mental health care has been a long-standing issue in Iowa. Five years ago last month, another Iowa family wrote a moving obituary following their 18-year-old son's suicide death, calling on lawmakers and policymakers to address the state's inadequate mental health resources.

More funding trickled down from the state level in the years before the pandemic, and many initiatives have popped up at the local level across the state.

Polk County officials, alarmed by the recent cluster of youth suicides, partnered with the state health department to ask federal experts to weigh in on improvements in mental health messaging. Akers said officials from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention examined the county's data.

Polk County Behavioral Health and Disability Services and Polk County Health Department have continued work on initiatives to address youth mental health, according to Nola Aigner Davis, spokesperson for the county health agency. Officials met with area hospital mental health administrators to coordinate services for those admitted for overdoses or attempted suicides.

Officials also gave more resources and materials to school nurses and other education staff during the spring and fall of 2022.

"Both organizations continue to work together with community partners to figure out the best ways to improve youth mental health in Polk County," Aigner Davis said.

Still, Aiden's family members say not enough support is being offered for families struggling to get the help they need for their loved ones.

Even after Aiden's first attempted suicide, his providers offered little follow-up, they said.

"We were trying to help, but we are not mental health professionals," Franci Phelan said. "We tried everything we knew, and we still fell short."

Laurie Phelan felt powerless to help her great-nephew, despite her role as the head of Iowa Jobs for America's Graduates, a nonprofit that helps provide development assistance to school-age kids navigating certain barriers, such as poverty or trauma.

"I run a program that should have saved him, but I couldn’t get it in the very school he was in," she said.

More:988 mental health hotline network is expanding, but rural residents still face care shortages

'We can't turn a blind eye,' Aiden's great-aunt says

Aiden is buried not far from his grandfather in a cemetery next to the small Catholic church where the family has attended Sunday mass for generations.

Aiden's remains were cremated and, in the family tradition, were buried using topsoil taken from the family farm he was raised on. Mourners tossed notes and flowers into the grave before picking up a shovel to scoop in the dirt.

Brock, Aiden's 17-year-old brother, was the one who finished filling the grave, shoveling the rest of the topsoil himself into the burial site.

Aiden's death has sparked a conversation within his community. At his wake and funeral, his great-aunts said they were approached by other students who were grappling with the same bullying, the same struggle to reconcile their identity in a space that wasn’t always accepting of them.

Aiden's great-aunts and great-uncle hope to give voice to others like Aiden. By telling his story to congressional and state leaders, they hope to spur change and provide more resources to the most vulnerable.

"We can’t turn a blind eye to structures that are failing our children and our parents," Laurie Phelan said. "We have to do the hard work of taking them apart and rebuilding them for a different generation for young people. We have to, because it’s worth a life."

Michaela Ramm covers health care for the Des Moines Register. She can be reached at mramm@registermedia.com, at (319) 339-7354 or on Twitter at @Michaela_Ramm.

More:Fired sergeant, citing colleague’s suicide, sues DMPD and calls for better mental health support

Need help for suicidal thoughts?

If you or someone you know is struggling and in crisis, free help is available 24/7 through the national Suicide and Crisis Lifeline. Individuals can connect with counselors anytime by calling or texting 988.

Know someone who may have suicidal thoughts? The 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline can also help you get your loved one the help they need.

The signs that someone may be at risk for suicide can vary. Here are a handful of the warning signs that someone may be having suicidal thoughts, according to federal officials:

Talking about wanting to die or looking for a way to kill themselves, such as searching for information online.

Feeling hopeless or trapped.

Talking about being a burden to others.

Increased use of alcohol or drugs.

Withdrawing or isolating themselves.

Extreme mood swings.

This article originally appeared on Des Moines Register: Iowan's suicide spurs family to call out lack of mental health care