Does Measure 110 need ‘a combination of coercion’?

Editor’s Note: This is the 5th in a KOIN 6 News series, “Breaking the cycle: Oregon’s attempt at recovery’

PORTLAND, Ore. (KOIN) — Measure 110 is Oregon’s experiment. The voter-approved measure garnered the votes of 58% of Oregon voters in 2020 to not criminalize drug addiction and to instead put more money into treatment.

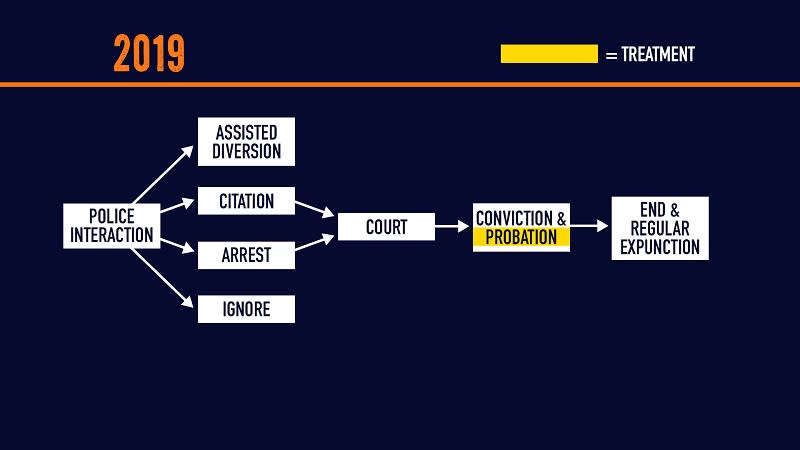

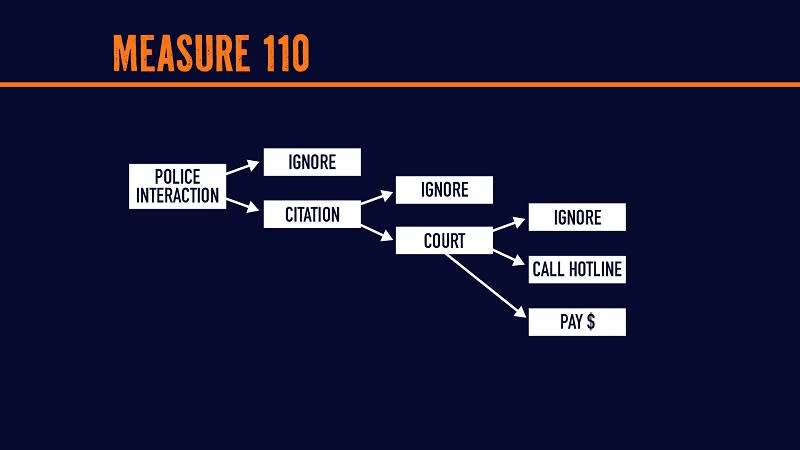

Measure 110 removed drug users from the criminal justice system and offered voluntary treatment.

Since its passage, the drug crisis has grown exponentially. Supporters of Measure 110 maintain it needs more time to show returns on investment. Opponents want to put the brakes on it and have proposed different ways to change it.

Rocky rollout

The rollout of Measure 110 was rocky, at best. Supporters said there were many issue at play — an affordable housing crisis, the pandemic and more dangerous street drugs.

“What we’ve seen is COVID has pulled the rug out of 50 years of disinvestment,” said Monta Knudson, the CEO of Bridges to Change. “What we see today around the streets is the impact from that. Unfortunately, M110 was passed at the same time all this has happened and so folks are pointing the finger on M110.”

Among those placing blame on Measure 110 are former Oregon Department of Corrections Director Max Williams and Washington County District Attorney Kevin Barton.

“Now we have open air street markets. We’re a haven for people who want to actually trade and commercialize the sale of these hard drugs — fentanyl, heroin, and methamphetamine,” Williams told KOIN 6 News.

“Measure 110 is the gasoline that was thrown on a fire that was already burning out of control,” Barton added.

Critics say Measure 110 lacks accountability, necessary incentives and consequences to get the severely addicted out on the streets into treatment. They point to records that shows more than 6,200 tickets were issued state-wide — and 75% of those ticketed failed to appear in court. Only 50 people completed the addiction assessment via the Help Hotline.

In its current form, critics don’t think Measure 110 properly balances public harm, safety and crime. But these critics don’t want to repeal Measure 110, however, they do want to make possession of hard drugs a misdemeanor again — yet still keep all the money that goes into addiction treatment.

“The idea that this is simply reverting back to the way things were is flat out not true,” Barton said. “I think if we were having this conversation in 2019 about Oregon’s response to addiction, we would all agree that things weren’t going that well then, either.”

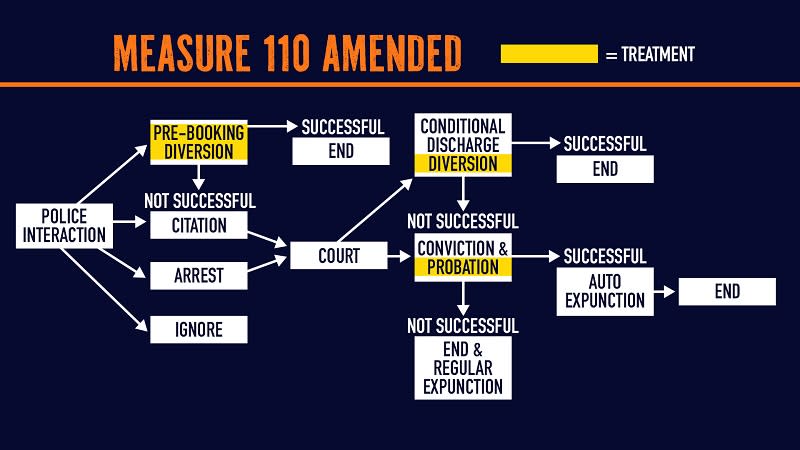

Barton said the group he’s affiliated with, Coalition to Fix and Improve Measure 110, “is interested in moving forward by taking the best parts of 110 and keeping them and enhancing them where we can, but also by building back in some measures of accountability to ensure that people actually engage in treatment.”

The options available

If a person is caught with drugs, the new amendment to M110 offers a choice: opt for treatment instead of court, but if treatment is refused a court will mandate it. Successful treatment results in a clean record.

“None of this is designed to put more people in jail or to rack up additional criminal charges. It’s all about trying to motivate people to effectively move towards treatment or recovery,” Williams said.

But some Measure 110 service providers don’t support re-criminalization of any kind.

“I think the carrot-and-the-stick approach that we’ve used for years hasn’t been very effective,” Knudson said.

But he agrees “the citation part of this legislation is ridiculous. It does nothing,” Knudson added. “Sending out peers to the streets to meet folks that could use services, I see that as possibly the most effective way to get that person into care.”

He cited data from the Oregon Health Authority that shows thousands of people are seeking Measure 110 services directly, emphasizing the need for a health care — not criminal justice — approach to addiction.

“I think there are places where diversion and other systems can be deployed to help motivate folks. But I think for possession only, it’s not an effective tool,” Knudson told KOIN 6 News.

Supporters of Measure 110, like Joe Bazeghi, are against required treatment.

“What we know as behavioral health and medical professionals at Recovery Works Northwest is that when folks voluntarily engage with treatment, they have better outcomes,” said Bazeghi, who helps run a new Measure 110 funded detox center in Southeast Portland.

His own journey to recovery led him to believe building trust is key to prevent relapse.

“We watch the process accelerate as folks begin to feel seen, they begin to feel that change is possible. They begin to experience hope,” he said. “Most people don’t want to be destitute and stuck in dangerous cycles of the self-administration of dangerous, contaminated street drugs.”

However, critics argue that for individuals grappling with severe addiction, consequences may be deemed necessary.

“What I would say is that when you compare voluntary treatment to mandatory treatment, voluntary treatment is always going to perform a little bit better,” said Williams, the former corrections department leader. “But that’s the wrong comparison. The comparison ought to be mandatory treatment versus untreated individuals on the street because they are the ones who aren’t voluntarily moving into treatment.”

He said a person has to decide they want to make that change.

“But the people who are down here right now at Ground Zero in Portland, they’re not at a position even to make that rational decision because they are currently so wrapped up in their addiction,” he said. “And while we let them try to figure that out, they’re doing untold damage to the community and to themselves.”

Critics of M110 cite research supporting the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of drug courts. However, specialty courts in Oregon lack historical statewide analysis. But new data from 2020-2023 shows 75% of drug court graduates did not reoffend with a new crime for 3 years.

Nevertheless, advocates of Measure 110 oppose the introduction of a new addiction court program, citing a scarcity of public defenders and expressing concern over its high cost.

But Washington County DA Kevin Barton said there is a cost no matter what.

“I think Oregonians need to recognize that we are paying a cost right now. And the costs that we’re paying right now is a cost that’s borne by our communities, by our businesses, by our families. There’s a cost with every person who dies from an overdose,” Barton told KOIN 6 News. “Yes, this will cost money to get people into treatment and to get to supervision. That’s not something we can do for free.”

Barton said their ballot measure to amend Measure 110 would require the Oregon legislature to find a separate sustainable funding source for their court-mandated supervision program.

However, Measure 110 supporters argue it will only shift the current bottleneck the state has in treatment to the courts.

“There’s this perception in the community right now that if we recriminalize, people are going to go to jail and then to treatment or they’re going to go to jail and off the streets — and it’s not going to work that way,” Knudson said. “Folks are going to possibly get arrested, possibly go to jail, and then they’re going to be for sure released. And so it’s unfortunate because we’re on a path for change right now. We have to change the system.”

“I reject the idea that this is us waging the war on drugs,” Williams said. “And in fact, I would argue that if we don’t intervene early with these people, the odds are they’re either going to die of an overdose after maybe having been resuscitated multiple times or, for many of them, they’re actually in pursuit of their addiction, going to commit a more serious person or property crime, and then they will go to prison.”

Research underway

Researchers from Portland State University are 2 years into a 3-year study looking at Measure 110’s impact on the criminal justice system and public safety.

“Although we have seen a decline in possession of controlled substance arrests, we still see this somewhat stable level of charging of drug-related offenses,” said PSU Associate Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice Dr. Kelsey Henderson. “I think that largely is because of this concerted effort to really kind of target more of the higher order offenses.”

Their study is examining law enforcement’s perception of Measure 110 in both rural and urban areas. Police claim they lost critical tools to chase larger drug dealers, such as search-and-seizure and informants.

“Law enforcement feels that they’re less proactive over time because of decriminalization. Ultimately, they believe that they play an important conduit and role in connecting the population that is suffering from substance use disorder into treatment,” said Dr. Brian Renauer, the criminology chair at PSU.

Law enforcement also reports the ticketing system is failing.

“They often use the term ‘there’s no teeth’ behind decriminalization,” Renauer said. “So, they have a strong belief that there needs to be some sort of coercive or legal sanction powers that can perhaps propel people into treatment opportunities.”

From his research, Renauer said he believes “a combination of factors” compels people toward treatment, but “that each individual would be different. Often in the background, there is that combination of coercion.”

Even with voluntary treatment, he said studies indicate ultimatums from external sources — like family and friends or pressure from the criminal justice system — influence people to get clean.

An OHSU analysis shows Oregon’s addiction treatment is half the size it needs to be. Yet, there are more than 300,000 Oregonians addicted to hard drugs, OHSU estimates. But even in the year when there were the most arrests, data shows officers only caught 16,000 drug offenders.

“Given the OHSU estimate that there is this very significant large population in need of treatment, our sense is we’re really going to need multiple tools. I’ll even use the term an army of professionals, outreach workers, social workers, treatment providers, criminal justice professionals,” Renauer said. “But we’re also going to need family and community realizing these opportunities and helping them.”

If voters are faced with another ballot measure, Renauer said they should consider the “most important component of Measure 110 is the increasing of resources for treatment opportunities for those suffering from substance use disorders that didn’t exist during the War on Drugs. So that’s the most radical, important change that I think the public should want to keep.”

He added, “We also need to address that issue of engagement. We know there’s this large population in need of treatment.”

The question, he said, is how to get people into treatment.

“History would say the War on Drugs didn’t help us do that. We can point to positive examples, but overall, it was not getting enough people into treatment and those treatment opportunities didn’t exist. Are we taking criminal justice out of that equation? That’s potentially concerning because what are we going to replace it with?

“So for the general public, our advice is that it’s too early to blame decriminalization for any of this sort of sense of chaos or fear, crime and disorder that they’re perceiving. There’s other factors that are related to that. And let’s give Measure 110 some more time.”

If legislators don’t make amendments in February’s session, Measure 110 will at least get another year. The earliest a reform attempt could make it to your ballot is November 2024.

And that’s about a month before the PSU study will conclude.

For the latest news, weather, sports, and streaming video, head to KOIN.com.