What does 'reverse racism' mean and is it actually real? Experts weigh in

The last month has been an intense period of reflection when it comes to racism. Perhaps you've also heard the term "reverse racism" in the media, on Instagram, at work or in pockets of mostly white communities in recent weeks. But what does the term really mean?

Before understanding the concept of "reverse racism" — the claim by white people that they've been victims of racism by people of color — Worku Nida, an expert in sociocultural anthropology with a Ph.D. from UCLA, says it's imperative to first break down the roots of racism in the U.S.

"Racism is a mechanism where resources and unfortunately power, wealth, prestige and even humanity are distributed along a color line. That’s what racism is about," Nida, who is currently an assistant professor in the University of California Riverside Anthropology Department, said.

TMRW interviewed Nida and other experts to understand what drives the idea of reverse racism and if the term is actually valid.

Types of racism

There are two types of racism, individual and systemic, which, according to Nida, are intertwined to reinforce and perpetuate racism in this country. So what are the differences?

Individual racism

Individualized racism is when a person in a position of privilege has some prejudice against another person based on the color of their skin.

"My practice and knowledge is that racism is the combination of two things: discrimination plus power over," Lynne Lyman, a justice advocate and former California state director for the Drug Policy Alliance, told TMRW. "Where a lot of white people get caught up and confused is that they may have felt discriminated against … but it's very different from racism when you don’t have the power. [Racism] can only come from the most dominant group."

The problematic pattern of individualized racism, according to Lyman, is that once you put a person who has been taught to have racial biases, overtly or subconsciously, into a position where they have any clout, their "personal racist tendencies" become "amplified and empowered."

For example, if one white manager at a company was racist against Black people and never hired Black people during a 10-year management period, it would eventually impact the entire structure and culture of the company. With no Black employees hired at entry-level positions, there would be no advancement for Black people into higher positions.

"Now that company's practice has been institutionalized over time with no room for Black people," Lyman told TMRW.

Lyman compared this to sexism, which by definition cannot be experienced by cisgender men because they have, historically and undeniably, been in positions of power over women. All it takes is one individual with racist or sexist tendencies in a position of power at a school, corporation, on a police force or in the government to cultivate a toxic culture.

Systemic racism

"Systemic and structural racism is rooted in institutions, actions and policies that allow certain groups of people to (advance) while preventing other people from having access to resources," Nida told TMRW. "This works through the court system, congress, presidency, through all levels of structures of government, in business, in education — you name it."

A "glaring" example of systemic racism, Nida said, is the G.I. Bill of Rights that was passed after World War II. Officially titled the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, the bill was designed to help veterans start their lives and families with low-interest mortgage rates, access to loans for education and training and other privileges.

"This is a very important landmark. The G.I. Bill created the largest group of middle class probably in the world and is how the U.S. economy really formed," Nida told TMRW. "Black and brown people fought alongside white people in World War II, and they were excluded from this, unfortunately."

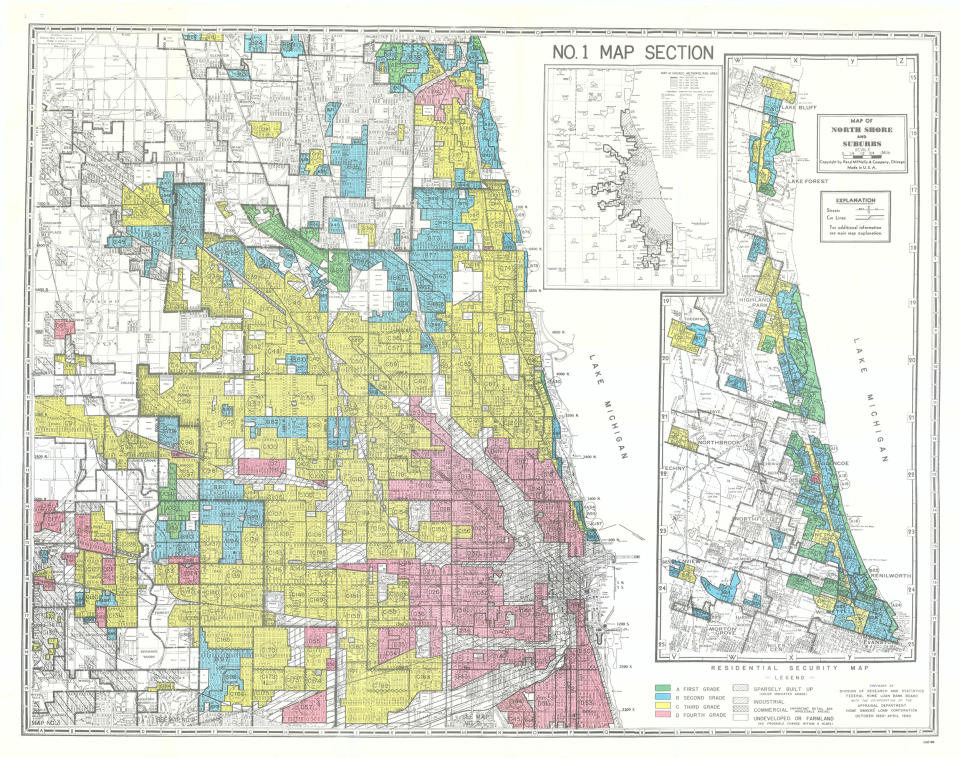

Passed 20 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, during a time when overt racism was the norm in many areas, the G.I. Bill required veterans to get benefits from a white Veterans Administration and loans from white bankers who refused them regardless of their eligibility. The V.A. also adopted "redlining," developed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt's 1933 New Deal. On a color-coded map of metro areas throughout the entire country, the Home Owners Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration circled places in red to indicate they were too risky to insure mortgages.

Anywhere a Black family lived or lived near was circled red. When Black people applied for loans, whether they had secured benefits from the G.I. Bill or not, they were segregated to areas within the red lines. If a Black family persevered through racist red tape to buy a house in one of the nicer, low-risk areas, there was "white flight," a concept referring to white people moving from an area to keep people of color separate.

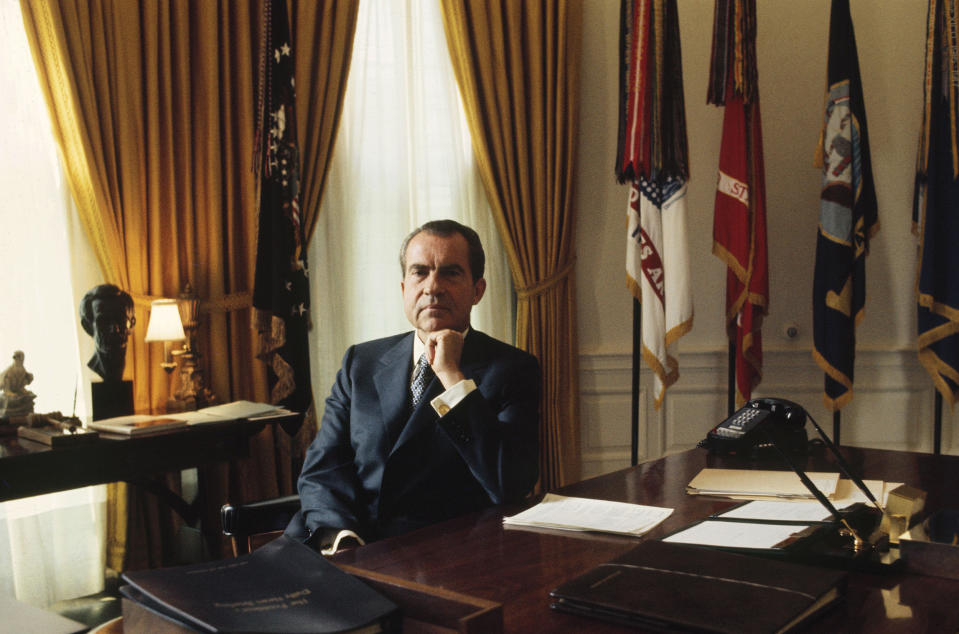

Another example of structural racism is President Richard Nixon's 1971 declaration of the "War on Drugs." Drugs, according to Lyman, were strategically made illegal to oppress certain minorities at different times throughout this country's history.

Laws created on "clearly" racist principles to keep people of color, minorities and immigrants oppressed and controlled, Lyman said, have continued to this day. This has culminated in drastic incarceration rates.

In a recent Harper's Magazine article, Nixon aide John Ehrlichman was quoted admitting the War on Drugs was a ruse to fight the Nixon White House's "two enemies: the antiwar left and black people."

"We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities," Ehrlichman said. "We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Some white people may diminish racism in 2020 by justifying that they, their parents or grandparents came from nothing and worked hard to get what they have. But federal legislation and structures like the G.I. Bill and the War on Drugs are crucial to understanding that hard work was not enough for Black Americans to overcome the structural barriers they faced.

Where does structural racism come from?

Both Lyman, who is white, and Nida, who is Ethiopian, emphasized that racist beliefs and structures in the U.S. were cultivated in anti-Blackness.

"White supremacy and white privilege are at the heart of and define structural racism. They were constructed historically and legally codified in 1691 in Virginia," Nida told TMRW. "Different plantation owners put on paper as the law that white Americans were superior to enslaved Africans and people of color, and had the right to own the land, to be in charge and to be in charge of slave labor."

When groups of enslaved laborers began to rebel against their exploiters and plantation owners, who were comparatively few in number, Nida said the ideology of white supremacy was crafted and distributed to all groups of white people. This promoted a political system that for hundreds of years would align working class and poor white people with the elite white people over Black communities with a similar socioeconomic standing.

"People weren’t just born racist because you grew up on this soil. It was a very deliberate, conscious and centuries-long marketing effort," Lyman told TMRW. "When the abolitionists started pushing out ideas that all humans are equal, a lot of which was based in Christianity and other religions on how you treat other people, in the South, (white people) knew there had to be a counter-narrative. It was like a slave labor PR Firm. Through the social media of the time (the printing press, public speeches, pamphlets), there was a very intentional effort to prove that Black people were inferior."

So, what about reverse racism? Can a person of color be racist against a white person in this country?

The term "reverse racism," according to experts on the subject like Lyman and Nida, is a mythological ideology that stems from discourse and propaganda on anti-Blackness.

With roots dating back to the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade, Nida says this concept has sprung up repeatedly through history: in the campaigns launched against abolitionists, in Jim Crow, in the War on Drugs, in the Civil Rights movement and still today in the Black Lives Matter movement in an effort to deflect and distract from the realities of the Black experience in this country.

"Affirmative action emerged in 1966 after the Civil Rights movement when the people of color and Black people included were given limited access to education. Doors were being opened to them that had been closed for centuries for no other reason than being who they are," Nida told TMRW. "Some white folks brought up the analogy of reverse racism. It’s a social lie, it doesn’t exist. (Because) if we're talking about dismantling systemic racism, we're talking about white supremacy and white racism. People who are benefiting from (those concepts) are not going to be happy with changes that affect the status quo."

Now, there are plenty of Black people in white-collar jobs who are loved and treated well by their white friends and colleagues. But the deeply embedded structures and federal laws passed by outright racists when outright racism was the norm still exist. A white person may not feel or be individually racist, but we live in a system that was designed to uplift white Americans and neglect the pain and suffering of Black Americans.

Racism stems from this imbalance in power. Before considering whether a white person has experienced "reverse racism," Nida urges you to ask yourself these questions:

When is the last time Black people and people of color forced white people to work on plantations?

When was the last time Black people and people of color subjected white folks to lynching?

When was the last time Black people and people of color excluded white folks from having access to the middle-class opportunities?

How many Black presidents have we had? How many Native American presidents have we had? How many Hispanic?

“A Black person can treat a white person poorly. A Black person can hate a white person for being white. But it’s this idea of reverse racism that doesn’t work,” Lyman told TMRW. “It’s never too late to see and acknowledge this kind of gross injustice and start to fight against anti-Blackness. You can never be too late to this party. We need to undo it in ourselves, in our communities, in our laws and in our society.”

For more readings on the topic of racism and Black experience in the U.S., Nida and Lyman recommend these books:

“The Denial of Antiblackness: Multiracial Redemption and Black Suffering" by João H. Costa Vargas

"The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness" by Michelle Alexander

"How to be Anti-Racist" by Ibram X. Kendi

"Stony the Road" by Henry Louis Gates