Don Bolles files: The bill that turned a reporter and father into an advocate for children

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The reporter had covered legislative activity for more than 20 years, 10 of them in Phoenix working for The Arizona Republic. But on this day in 1973, Don Bolles was not reporting a story. He was advocating for his daughter, who was born with a hearing impairment.

“I speak on behalf (of) my 3-year-old daughter, who is listed by audiologists as profoundly deaf,” Bolles told state lawmakers on the House Education Committee. “And for her Gompers Rehabilitation Center classmates who face the prospects of growing up hearing only minimally, if at all.”

Don Bolles was an investigative reporter for The Arizona Republic. In 1976, he was killed while pursuing a story. Join us for the journey and share what you remember about how the Arizona of Don Bolles’ era became the Arizona of today. Join the conversation on Facebook. And contact us here.

In his time covering the Legislature, Bolles had earned the respect of lawmakers, bureaucrats and party officials.

So it was with that bearing that Bolles turned into an advocate. He put the credibility he earned to use in service of his daughter and, by extension, to all hearing impaired children in the state of Arizona.

Bolles testified before lawmakers in support of a bill that would require all school districts offer special education at neighborhood public schools.

Bolles would become most known for the way he died. He was killed by a bomb planted under his car and detonated by remote control. He would be numbered among the few reporters in the United States killed because of their reporting. Authorities would conclude Bolles was killed because his articles cost a liquor magnate a seat on the state’s racing commission.

But his most enduring legacy in Arizona arguably came on March 21, 1973, more than three years before his death, when Bolles helped lobby for a bill that forever changed the way every child with extraordinary needs in Arizona was educated.

His wife, Rosalie Bolles Kasse, said the couple met other families who had also enrolled their children in services through the Gompers center, children with varying disabilities.

"He was fighting for (all) kinds of special-needs children to have an opportunity to be their best," Kasse said in a November interview.

The story of how Bolles argued for mandatory special education in Arizona was discovered in a trove of files and audio recordings in a series of cabinets that had been padlocked. The Republic has been sorting through the materials for the past year, finding insights into Bolles as a reporter.

And, in this case, as a father.

Nowhere for hearing-impaired children to go

Bolles' prepared typewritten statement to the House Education Committee was found among his files, in a folder that also contained clippings and notes about the pending legislation.

At the time of the hearing, visually or hearing-impaired students were offered free education in two schools run by the state: the Arizona School for the Deaf and Blind in Tucson or the Phoenix Day School for the Deaf.

Some districts offered piecemeal opportunities. Five districts in the Phoenix area employed a teacher who specialized in educating hearing-impaired students, according to Bolles’ testimony. At the high school level, the Phoenix Union District employed two teachers and the Glendale district employed one part time.

“I talked last night with a mother of a deaf child in Paradise Valley,” Bolles told lawmakers. “She has nowhere for her child to go when she reached school age.”

The main concern over the bill was its estimated cost. A fiscal note attached to the bill said it would cost $14 million. But one lawmaker said that was not accurate as there was no way of determining how many children would be eligible for the services.

Advocacy in The Republic newsroom

One opposing voice came from Earl Zarbin, who was both an editor at The Republic and a member of the Madison Elementary School Board. Zarbin said his own Madison district, which offered special education, had seen the costs of providing it go up fivefold in the previous two years.

Zarbin, interviewed in November, said his opposition to the program was in line with his Libertarian philosophy that would have called for eventually dismantling government-run education in favor of a private system.

Zarbin said he decided to run for the board because he had school-age children in the district and wanted to make sure it was being run well. He said he did not seek permission from his bosses at The Republic before doing so. He wasn’t sure how the publisher, Eugene Pulliam, felt about his tenure on the school board, Zarbin said, but some newsroom editors frowned on it.

PODCAST: Listen to "Rediscovering: Don Bolles," his story told using his own voice.

“One thing the newsroom was conscious of was that we not engage in any kind of private doings that might in any way give anyone the idea that the newspaper was biased towards anybody,” Zarbin said.

He said he was kept from editing certain stories about education while he served on the board.

It would have been unusual for Bolles to advocate openly for a piece of legislation. He acknowledged as much when he testified to lawmakers, making it clear he was speaking for himself only as a citizen and father, not representing The Republic.

Kasse said her husband told Pulliam he was going to testify in support of the change in the law. Bolles testified with the boss' blessing, she said.

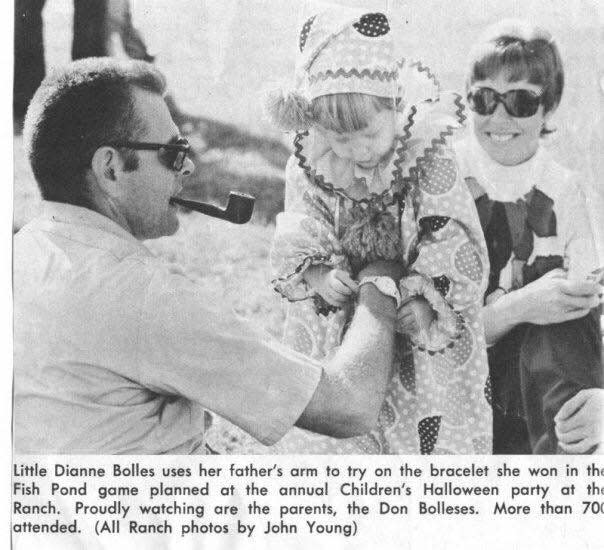

Bolles was held in high regard by Pulliam, both as a reporter and as a father. The publisher paid for the first hearing aids for Bolles’ daughter, Diane.

The hearings aids helped Diane's development.

“She said her first words like two months after she had her hearing aids,” Kasse said, during an interview at her home in South Carolina.

Bill passes with budget worries

In his testimony to lawmakers, Bolles made reference to his job.

“Sitting here week after week, I know your concerns about the high demands of the educational sector on the budget and on the total state finance picture,” Bolles said.

Bolles offered some deep-in-the-weeds policy prescriptions for funding the proposal. He also offered an argument that hearing-impaired children like his daughter deserved state support.

“To understand what they face, try sometime to cover both your ears tightly and try to understand someone who is talking to you,” he told lawmakers. “But not just now, please.”

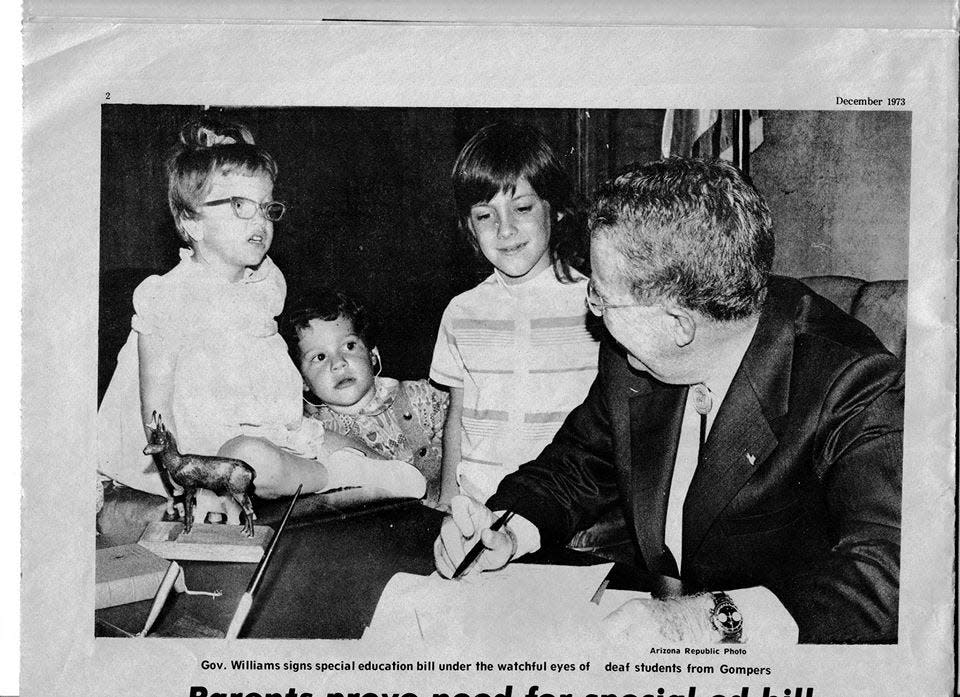

The bill passed both chambers and was signed into law by Gov. Jack Williams in May 1973. Diane Bolles was among the children who attended the bill-signing ceremony.

The bill would not require schools to implement special education until September 1976. As feared, the estimated costs rose to $29 million rather than the budgeted $16 million. And a slowing economy put a crimp on the state’s finances.

Lawmakers considered pushing back the effective date of the law, or restricting the number of students who could take part.

Bolles testified again to ensure funding

Bolles would testify again, this time before the Senate Select Committee on Special Education in February 1975. Once again, he began his testimony by emphasizing that he was speaking only for himself.

“It’s been alleged that I had something to do with passage of the special education act,” he told lawmakers, according to his prepared typewritten remarks. “In today’s context, I’m not sure if I should be proud or go hide somewhere.”

Bolles said he understood the fiscal woes of the state. But, he said, lawmakers should consider the children involved.

SUBSCRIBE: Help support high-quality local journalism like this.

“They are not meaningless ciphers in some impersonal budget format, but living, breathing, spontaneous, unique human beings,” Bolles said.

Bolles quoted the Arizona Constitution that mandated the legislature to provide a system of common schools for all pupils. In his typewritten testimony, Bolles put the word “all” in capital letters. Bolles said the parents group he was involved in might consider a lawsuit and, should a judge enforce that language, it would take the matter out of the Legislature’s hands.

“Arizona has delayed too long in requiring special education facilities,” Bolles said. “Postponing action now will make it more painful and more costly.”

A journalist and a father

The fight over funding of special education would continue into June and become part of contentious budget debates. Lawmakers eventually agreed to kick in more money to fully fund the implementation of the programs, but introduced a complicated funding formula that capped future outlays at $40 million.

In November 1975, the federal government passed a similar measure that ensured children with disabilities could attend public schools.

The fights over funding did not end. But Bolles helped Arizona pass its mandate two years ahead of the nation.

Motivated, his widow said, by his daughter. She would go on to take classes at Northern Arizona University. She lives in South Carolina and is a mother to four children.

"He was trying to step out of his role as a journalist," Kasse said, "and be an activist for the whole community of special-needs children."

Lost to Time: From the Don Bolles files

→ 'God, it must be Don': The Republic scrambled to cover the bombing

→ The bill that turned the reporter into a children's advocate

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Don Bolles files: When a reporter fought to get a bill passed