We don’t need to erase Florida’s Spanish heritage to fight modern-day racism | Opinion

The international statue wars have arrived in multicultural Miami, a city of refuge dubbed ”Gateway to the Americas.”

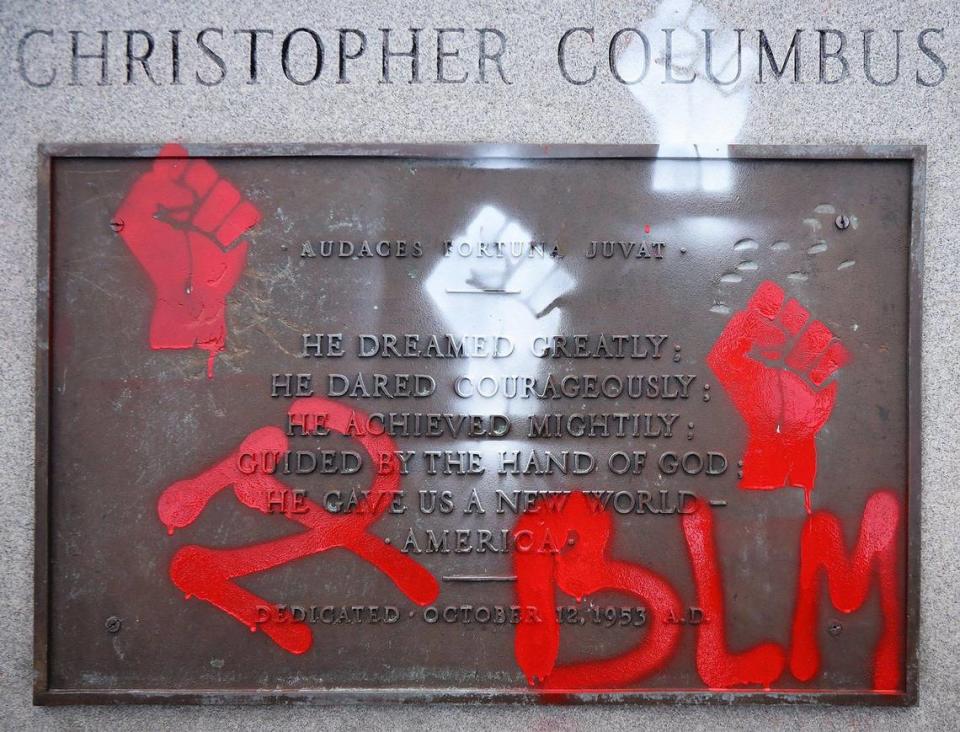

With no Confederate symbols on the town square to topple, a handful of Black Lives Matter protesters last week painted in red and tagged with provocative symbols the bronze statues of explorers Christopher Columbus and Juan Ponce de León in Downtown Miami.

For many Hispanics, even those who support the movement to end racial injustice and demand police accountability, it was jarring and confusing.

In the midst of a national reckoning with the dehumanizing legacy of slavery and racism in the United States, the question is: Do we also need to attack and erase Florida’s Spanish heritage to fight modern-day ills?

“It’s a stretch to connect Columbus and Ponce de León with what is going on today,” said Paul George, resident historian at History Miami Museum, who adds that when he saw what was done to the statues, “I was perplexed. As a historian, I don’t like the idea of erasing history.”

But the taggers and other activists and academics calling for or supporting the removal of Columbus statues elsewhere in the United States are expanding the movement against racism, police brutality and the crime against humanity of slavery to include colonialism, too.

They see the historic figures of Columbus or Ponce de León as not far removed from slavery.

In fact, according to History.com, some researchers believe enslaved Africans were brought to places like Florida in Spanish expeditions before the first English slave ship arrived in the Jamestown settlement of Virginia in 1619.

“I consider the demolition and painting necessary at the present moment,” said Odette Casamayor-Cisneros, a Black Cuban writer and associate professor of Latin American and Caribbean Cultures at the University of Pennsylvania. “These are the desanctifying gestures that our times urgently require.”

She doesn’t feel any lessons are lost by changing what statues belong in the public realm.

“The demolition of a statue does not deny the history,” she said. “What happened years, centuries ago, can no longer be undone. What it is possible to undo — and must be undone and reinvented — is the narrative, the knowledge that keeps us sanctifying and reproducing only one version of the facts.”

Listen to the rage accumulated over the last 500 years of injustice and inequality, she urges.

I see merits and flaws to all facets of this controversy.

Slavery is the original sin. Systemic racism is its modern-day version — and it exists, too, in the Miami we celebrate as a model of diversity.

I’m highly aware that often our multiculturalism serves to camouflage an ugly undercurrent of racism in Greater Miami. The mostly white-Hispanic counter protests to Black Lives Matter in the county put some of it on display.

But as a Miamian, a former visual arts writer and a traveler who roams the world soaking up cultures whose history comes alive in statues, enduring architecture and monuments, the vandalism of the Bayfront Park statues concerns me on a multitude of levels.

The criminal act — for which seven young men have been charged — seemed a divisive distraction from the impact Black Lives Matter‘s “call to action in response to state-sanctioned violence and anti-Black racism” is having here and nationwide.

The tags on the statues blended hammer and sickles, the Soviet symbol of communism, with Black Lives Matter symbols. It was instantly interpreted as an affront to the hundreds of thousands of communism’s victims in Miami, Black and white.

Isn’t the goal to win hearts and minds on behalf of equal justice now? Why alienate people who trace their ancestry to Spain and revel in the richness and diversity of U.S. Hispanic and Latin American culture?

In an immigrant county like Miami-Dade, which is 70 percent Hispanic, heritage is the pulsing heart.

If the statues had been of odious, treasonous Confederates like Ku Klux Klan founder Nathan Bedford Forrest — a hero to racists and supremacists who want to whitewash his biography — take them down, no question about it. Long overdue.

Columbus and Ponce de León

But the Genoese Columbus isn’t directly tied to slavery by hard evidence.

“The timeline fits,” was all the story on the subject in History.com offered by way of connection between Columbus and the first ships carrying Africans, free and enslaved, to the New World. What isn’t challenged is motivation: Columbus came upon our continent in 1492 on a mission for the King and Queen of Spain searching for a new trade route to Asia.

In a similar vein, the fabled Ponce de León, who first sailed to the Americas on Columbus’ second expedition in 1493, came upon Florida in 1513 after a feud over the governorship of Puerto Rico with Columbus’ son, Diego.

He sailed off on King Ferdinand’s advice that he explore the Caribbean Sea — and eventually landed among mosquitoes and mangroves in Key Biscayne, naming it Santa Marta and claiming it for Spain. (Although he reported finding a fresh water spring in the key, there’s no evidence that de León was searching for the famous Fountain of Youth. Florida, however, has milked the story for tourism purposes as long as it has been around.)

Ponce de León also gave Florida its name, La Florida, most likely because he made the discovery at the time of the Easter feast’s festival of flowers, Pascua Florida.

Yes, the conquest of the Americas that followed — not only from the Spanish but the English, French, Dutch and Portuguese — was bloody and ruthless, and the thirst for wealth led to slavery.

But when I asked experts about how this history plays into what we’re living today, I found no easy answers or consensus, only intelligent observations to ponder.

“For Hispanic Americans, these statues have a special importance that goes beyond particulars,” said Maricel Presilla, a food historian, author and chef who has delved deeply into the study of Columbus’ life. “Ask Dominicans if they want Columbus erased from their history and the colonial city, which is so linked to Colón, stripped of any reference to that moment in history.”

Perhaps not in Hispaniola, but in the Bahamas and in Trinidad and Tobago, people want monuments to Columbus removed. And in Barbados, thousands are demanding the toppling of a colonial-era statue of British naval commander and slavery sympathizer Horatio Nelson in the wake of U.S. protests over systemic racism and George Floyd’s death.

People in these Caribbean nations want statues of Columbus and Lord Nelson taken down

‘Canned hatred’ for Columbus

Presilla calls the attacks against Columbus in the United States “canned hatred.”

“When statues are vandalized or tumbled without the consensus of an entire community and any history is reduced to sound bites, it is the sign that virtuous righteousness has become censorship,” said Presilla, a white Cuban American. “Whoever has studied Latin American history seriously understands who Columbus was and what the voyages of discovery meant in all their complexity, pain and far-reaching impact on world history.”

Echoing the sentiments of Miamians I interviewed, she added: “They made us who we are, including the foods we eat. Whoever has read the best biography of Columbus by the Harvard historian Samuel Eliot Morison and studied the history of the early Spanish colonial period through primary sources can’t cast this individual as only the villain of the story and nothing else.”

Marking Miami history

In Miami, the Europeans aren’t alone in the statue department.

A striking statue of a Tequesta warrior and his family, by Cuban-born sculptor Manuel Carbonell, towers over the Brickell Avenue bridge.

Bronze reliefs on the bridge honor six prominent Miamians — founding “mother” Julia Tuttle, railroad magnate Henry M. Flagler, pioneers William and Mary Brickell, Black pioneer D.A. Dorsey, and environmentalist and writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas.

Preserving history, however, has been an uphill battle in Miami, a city in a perennial state of development.

We can’t afford to be reductionist.

“We know little about our heritage and we’re going to take away two statues people looked at and pondered, what is the history here?” George said. “By removing the statues, you’re removing the opportunity to read historical markers and get a sense of what happened. The teacher in me thinks people need these guide posts.”

Instead, George suggests adding historical markers, “pointing out the pros and cons of people being showcased in statues.” Or, moving the statues from the public park to a museum where they can be put in context and explained.

Others I talked to posed a larger question: If a figure as distant from current events as Columbus needs to come down, what about the slave-owning Founding Fathers? Are we changing the name of Washington D.C.? Renaming the Washington Monument?

Do we oust Columbus Day from the calendar and the Columbus Day Regatta from Biscayne Bay?

“Every revisionist moment purporting to do good by rewriting history ends up becoming a tyranny that even justifies vandalism as just collateral damage,” Presilla said. “Defacing a statue in the name of goodness is as wrong as trying to silence any differing narrative, particularly in times of crisis such as the terrible moments that we are experiencing today.”

Black Cubans and Columbus

But many Black Cubans see hispanidad as Eurocentric — and this moment of revolt even against statues as necessary.

Taking down a Columbus statue, Casamayor-Cisneros said, “means that his position as a supposed ‘discoverer’ and founder of an entire continent has to be inexorably reviewed. That is the call inscribed within the act of knocking down, decapitating and defacing.”

She has the same opinion of Ponce de León, “but I understand the political importance he represents for Latinos in Florida.

“In this case, the question I ask is this: Is a Spanish conquistador being celebrated only for being Hispanic to the detriment of the consequences his actions as a conquistador had on the indigenous populations of Florida?”

She doesn’t feel taking down the statues erases heritage. They “only glorify a part — the dominator — of that heritage,” she said.

“They do not consider the Latin American totality, only the Spanish hegemonic power over our nations. They hide and distort the reality of Latin American ethnic composition and history. To persist in maintaining them is to perpetuate Eurocentric hegemony in the Americas, and with this, the indigenous, the Black, the mixture that we really are, are diminished.”

Educational opportunity isn’t wasted by the removal of “monuments built to perpetuate the memory of the foundations of the same system that oppresses” people today, she said, as they did the last 500 years.

Graffiti writing, removal, decapitation of statues is “perhaps only half the work,” she said. The other half is the rewriting of the official history being questioned.

“What is necessary at the moment is to summon and promote the participation of all sectors of society in the narrative of reinvention: the narrative that determines which events and which individuals are sacred, are monumentalized and respected.”

This is only possible, she added, “with the active help of those who have never been invited to write it, those whose only relationship with that story has been restricted to acquiescence, acceptance without hesitation.”

Casamayor-Cisneros invites reflection rather than condemnation of the defacing.

“It is essential to promote reflection on the phenomena that have caused systemic destruction and rage,” she said. “Not to understand this is to renounce the possible empathy, is to refuse to listen to the fellow citizen, who is also part of that Latino community.”

She added: “Public space is no longer just the exclusive property of white. It is also, equally, the Black, the indigenous, the descendants of those enslaved and massacred under the order imposed by the characters immortalized in statues.”

We’re hopefully writing today the first draft of the history of a time that once and for all rejects racism.

Part of the reckoning is deciding what statues belong in the public realm, and which, like the beheaded busts of Romans, belong in museums.

Some monuments resonate more than others with current injustices. We should hear the claims, acknowledge them, and find a way to mark history without enshrining or seeming to enshrine the unworthy.

It’s shouldn’t be an either/or in Miami, but an us.

We don’t need to negate Florida’s Spanish heritage to fight modern-day racism.