‘You don’t give up on family’: Adoptive parents’ quest to help foster daughter meets tragic end

Tina Chase climbed the county courthouse steps, choking back grief and anger. She had a promise to keep.

For three years, Tina and her husband, Mark, had waited for this day – the day their foster daughter, Becca, would legally become theirs. Had they taken the time to imagine it, they might have pictured something like the adoption ceremony happening two floors above them: balloons, boisterous laughter and celebration.

Instead, Tina quietly pushed her way through the glass revolving door, cleared security and turned left toward the golden bank of elevators, with Mark by her side.

As they rode up the elevator, Tina thought back to all the delays to get Becca help. The months it took to schedule Becca’s first mental health evaluation. The years of pushing for intensive mental health services.

What would today have been like, Tina wondered, if Becca had gotten those things sooner?

Tina pressed a stack of picture frames to her chest as the elevator carried them to the third floor. She and Mark stood in the courtroom with their attorney, Becca’s best friend, her Girl Scout troop leader and a Department of Child Services family case manager.

Only one person was missing: Becca.

Video: Memphis mom touches the lives of 75 foster kids

‘She was our Christmas gift’

Mark and Tina met the girl who would become their daughter a few days after Christmas in 2016.

The 9-year-old arrived at the front door of their home in Fishers, Indiana, clutching a trash bag filled with everything she owned: three small cat stuffed animals, two unicorns, faded clothing, socks without a match and a ragged blanket.

By then, the pint-sized brunette had spent more than half her life in the child welfare system. Becca would not be returning to her biological parents, and the Indiana Department of Child Services was seeking a permanent home for her.

The agency hoped Mark and Tina might be it. The Indiana couple were relatively new to being foster parents, but they went into it with the goal of adopting an older child.

“As soon as I laid eyes on that little girl, I said this is forever,” Tina recalled.

Bouncing as she walked into the couple’s home, Becca chattered excitedly about how happy she was to be there. Within minutes, she was referring to Tina and Mark as “Mom” and “Dad.”

“She was our Christmas gift,” Tina said.

‘Ghosts, be gone’

Becca’s first six months in the Chase home were idyllic. She joined the local Girl Scout troop. She cuddled on the couch watching space documentaries with Mark and anime with Tina. At the dinner table, they competed to see who could make the others laugh the hardest.

When Becca said she was having trouble sleeping at night because she thought her bedroom was haunted, Tina said she did the only thing she could think of. She bought a stick of sage, lit it and watched Becca wave it around the room, saying “ghosts, be gone.”

Other ghosts were more difficult to exorcise.

Mark and Tina said child welfare officials had told them Becca suffered physical, sexual and emotional abuse before moving into their home. As she became more comfortable, Becca shared more details.

“If there’s a kind of abuse, she had gone through it already before she came here,” Tina said. “Which is a lot to take in and explains a lot about her behavior.”

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

Your browser does not support the video tag. Becca Chase talks to Tina Chase about making homemade play dough. Provided by the Chase family

For all the joy she brought into Mark and Tina’s lives, Becca struggled with her own emotions. She was quick to become frustrated. The 9-year-old knew how to read body language and facial expressions and tried to manipulate people to get her way. When that didn’t work, she threw tantrums – screaming, hitting, kicking and breaking a mirror or toys.

“We’ve tried time outs; we’ve tried time ins; we’ve tried grounding from various electronics and playtime with friends; we’ve tried behavior charts; we’ve tried token jars for good behavior; we’ve tried offering explanations for answers every time; we’ve tried writing lines,” Tina wrote in a 2018 Facebook post. “Nothing seems to be working.”

Sometimes Becca threatened to run away. Maybe they had asked her to do her homework. Or to finish her chores. Whatever it was that made her angry, Becca would run for the door. It played out the same way time and time again: Mark blocked one door, Tina the other, then Becca ran to the garage.

“That’s three exits and two of us,” Mark said.

When Becca got outside, she wouldn’t go far. Mark said the little girl just hurried down the sidewalk, glancing back to make sure Mark or Tina was following her. She’d slow her pace until one of them caught up. Then they’d return home together.

“I think it’s just because she needed the people to say, ‘No, no, no, we need you here,’” Tina recalled. “‘We need you in our lives.’”

In the spring of 2018, the couple hired an adoption attorney to solidify Becca’s place in their lives.

A fight for mental health services

Meanwhile, Tina and Mark pushed state officials to have the girl evaluated and diagnosed so she could get the mental health treatment she needed.

The decision wasn’t theirs to make. Becca’s adoption was not yet final. The child welfare agency was still her legal guardian, and only it could decide which services she could receive.

Getting agency approval was only the first hurdle. Limited options and long waits for providers who accept Medicaid also created barriers to access for the Indiana couple – as for families throughout the U.S. both before and after adoptions. Multiple families told USA TODAY they also faced challenges finding mental health providers who were specifically trained to work with children who have been abused.

The American Academy of Pediatrics called mental and behavioral health “the largest unmet health need for children and teens in foster care.”

Dr. Lisa Zetley, a pediatrician and medical director for a foster care medical program in Wisconsin, said children are affected by their environments, so it’s important they have safe, stable and nurturing relationships.

“When children don’t have those experiences, either because they experience neglect or maltreatment in the form of abuse, that really impacts not just their current being, but their long-term trajectory,” said Zetley, who also chairs the Council on Foster Care, Adoption and Kinship Care for the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Yet access to mental health care for children in the system can be disjointed and disrupted by changes in their living situations and other factors.

Tina said it took months to schedule Becca’s first 45-minute mental health evaluation.

After that appointment and several others, Becca was diagnosed with numerous mental health concerns: depression, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, a condition characterized by extreme irritability, anger and outbursts, letters provided by the family show.

Becca’s behavior continued to intensify in 2018 – especially after she learned her biological mother had been murdered. Becca, who had turned 10, started throwing glassware and books and running away more frequently, and her talk of suicide turned into real attempts.

“I’m learning new ways to cope so that I can make sure that I’m doing OK and not doing too much stress or pressure on myself,” Becca said in one video recorded for Mark and Tina during an inpatient stay at Community Hospital North Behavioral Health Pavilion. “And as you know, I love you at all times. And that will never stop.”

Becca cycled through three therapists who came to their home, two behavioral therapists, two psychiatrists, therapy using horses and two weeklong stays in a mental health facility. Nothing seemed to help. Mark and Tina called the police multiple times because of Becca’s threats to her own safety. They locked up their kitchen knives and conducted weekly body checks to make sure she hadn’t harmed herself.

Tina said family case manager Amber Pierce even visited outside work hours to bake cookies, color or go for walks with Becca.

Tina and Mark said they believed Becca desperately needed a longer-term stay in residential placement, where she could be supervised 24 hours a day, receive intensive mental health services and be properly evaluated and diagnosed. But senior child welfare officials denied the request, in part because a therapist who saw Becca once a week for 45 minutes reported the little girl was fine.

Mark and Tina felt helpless because they knew she needed more.

“We went around and around and around with the clinical services division,” Tina said.

Tina said she was particularly infuriated by one of their questions: If we put Becca into a residential facility, is the family still going to adopt her?

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

.cta-container {border:4px solid #364858;margin:30px 0;padding:30px;width:100%;}.cta-container .headline {margin:0 0 9px;font-family:'Unify Sans', Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;}.cta-container .chatter {margin:0 0 18px;font-family:'Unify Sans', Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;font-weight:400;}.btn-container {background-color:#364858;cursor:pointer;display:inline-block;}.btn-container .btn-link {text-align:center;text-decoration:none;width:inherit;}.btn-container .text-container {font-family:'Unify Sans', Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;font-size:12px;font-style:normal;font-weight:600;padding:12px 15px 11px 13px;}.btn-container .icon-container {background-color:rgba(0, 0, 0, 0.15);padding:7px 6px;width:24px;}.btn-container .icon-container svg {display:block;height:24px;width:24px;}.chatter-more {font-family:'Unify Sans', Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;font-weight:400;font-size:14px;color:#404040;padding-top:10px;}@media all and (min-width:960px) {#container {margin:0 auto;padding:30px 40px;}} Help USA TODAY investigate adoption

Are you an adoptee, parent, community member or public and private employee who can help us learn more about adoption issues? We want to hear from you about disrupted and dissolved adoptions.

Fill out this form

‘You don’t give up on family’

There were times, after a major tantrum or a suicide attempt, when Mark and Tina checked in with each other to make sure they still wanted to adopt Becca. Every time, the answer was yes.

“If we did give up on her, we knew that that would be so devastating that there would be no recovery for her,” Mark said. “If in her state, we were to say, ‘No, I’m sorry, but you – you can’t be with us. The adoption is canceled. You just need to be with somebody else now.’ I can’t even imagine what that would do to a child. We would not be able to live with ourselves.”

“You don’t hand family over to someone else, you know? You don’t give up on family,” Tina said. “So I had no intention of giving up on her.”

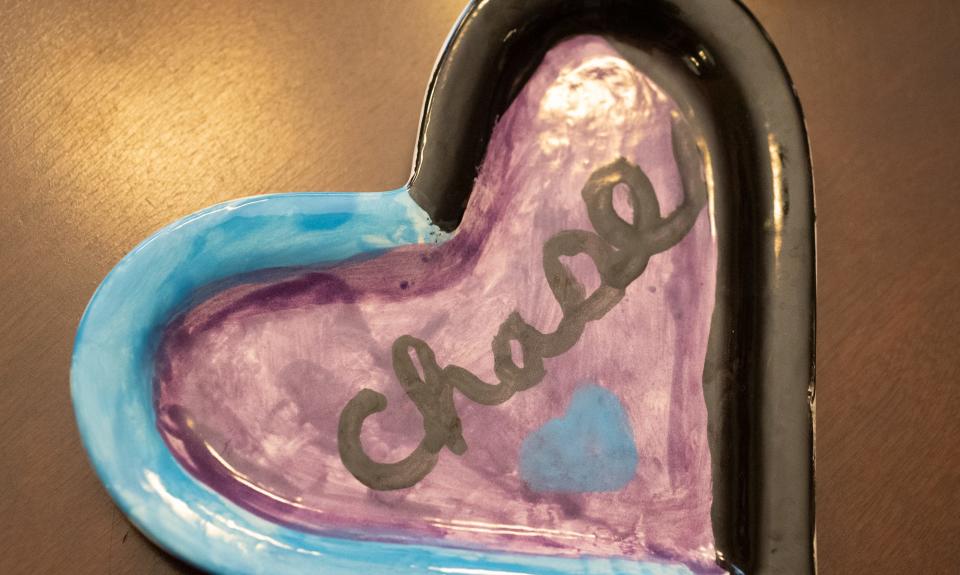

They spoke frequently with Becca about their commitment to adopting her. In their minds, Becca was already a Chase. An adoption hearing would give her the last name. You’ll go to the court and be ours forever, Tina said.

Their attorney, Shelley Haymaker, had filed the formal petition to adopt in September 2018.

Since then, Mark and Tina’s interactions with the child welfare agency had become two-pronged: secure services for Becca now and negotiate an adoption subsidy to ensure she could access needed services after adoption.

The state’s initial adoption subsidy offer: $10 a day.

Mark and Tina were receiving $66.32 a day to care for Becca.

Haymaker countered the state’s offer, asking for $60 a day.

In letters to the agency, Mark and Tina tried to explain why $10 a day would not be enough. They outlined Becca’s medical and therapeutic needs, noting Medicaid could not meet those needs and private insurance would cover only some of the cost. By then, Tina had quit her job to spend more time with Becca.

Mark told the child welfare agency the services Becca needed were “beyond our ability to provide.”

“This may be a line item to you, but this is also a young girl’s life,” Tina wrote in her letter.

The state’s next offer: $35.

Subsidy negotiations slowed in 2019 as Becca’s mental health worsened and her suicide attempts turned more serious.

The state eventually agreed Becca, then 11, needed services that only residential placement could provide. The agency found an emergency bed at Gibault Children’s Services, a facility about an hour and 45 minutes away in Terre Haute, Indiana. Becca lived there for about a month.

Mark and Tina continued to update Becca on the status of her adoption. Ashlie Delph, a former foster youth who lived with the family at the time, said Becca wanted to believe the adoption would happen, but one of her biggest fears was never having a family. And people had broken promises to her before.

In August 2019, Damar Services opened a residential program in Indianapolis, and the child welfare agency secured a bed for Becca. Mark and Tina were thrilled because Becca would be closer to home. They were also told the facility had one-on-one supervision and a comprehensive evaluation process. Finally, they thought, Becca would get the help she so desperately needed, and she’d be safe.

Then Tina’s phone rang.

Gone too soon

A little over a week after Becca was transferred to Damar, the Indiana Department of Child Services called with a devastating update.

Becca had tried to take her own life, the official told Tina, and this time she had gone further than before. She was on a ventilator at the Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis.

“I couldn’t believe it at first,” Tina said. “I was like: ‘What are you talking about? She’s in this place because she can be watched, and they can stop her.’”

Tina was visiting her mother in South Bend, so Mark arrived at the hospital first. The doctor gave him a summary of what the hospital knew and warned, it doesn’t look good. But there were more tests to run.

“There was still some hope that night,” Mark recalled. “But part of me knew that lack of oxygen for eight minutes to the brain – I knew what that meant.”

The test results came in the next day. Becca has significant brain damage, the doctor said. She isn’t going to make it.

Her heart was still beating, but their daughter was gone.

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

.-suicides-cta-container {border:4px solid;margin:30px 0;padding:30px;width:100%;}.-suicides-cta-container {margin:0 0 9px;}.-suicides-text-container {font-family:"Unify Sans", Helvetica, Arial, sans-serif;font-size:12px;font-style:normal;font-weight:600;padding:12px 15px 11px 13px;}.-suicides-chatter a {}@media all and (min-width:960px) {.-suicides-cta-container {margin:0 auto;padding:30px 40px;}} If you are having thoughts of suicide (or know someone who is), call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for confidential support any time day or night: 800-273-TALK (8255); or chat online at suicidepreventionlifeline.org.

Crisis Text Line also provides free, 24/7, confidential support via text message to people in crisis when they text HOME to 741741.

When Becca’s adoption failed before it was complete, she became one of the more than 4,600 children who have died in foster care in the U.S. since 2008, according to a USA TODAY analysis of federal data.

Mark and Tina were asked whether they wanted to donate Becca’s organs, and they said yes. She would never have the chance to drive or go to prom, but part of her would live on through others.

Becca remained on life support while medical personnel coordinated her donation. As the couple grieved at their daughter’s side, nurses stopped in to check on them and offer support. Members of Becca’s Girl Scout troop and their parents, friends, her principal, teachers and state workers ducked in and out of the hospital room.

Eventually, it was time to say goodbye.

Tina bent close to her daughter and whispered the plot of “Divergent,” by Veronica Roth, a book they’d been reading together at bedtime, so Becca would know the ending. Then Tina shared her love.

Goodbye, she said quietly. I'll see you again.

Crying, Mark pressed his lips to Becca’s forehead and whispered his own simple “Goodbye.”

.oembed-frame {width:100%;height:100%;margin:0;border:0;}

A promise kept

A couple OF months after Becca’s death, Mark and Tina’s adoption attorney, Shelley Haymaker, contacted them with an offer.

Haymaker said she knew how much the couple had wanted to legally make Becca part of their family, so she had asked the child welfare system and county judge for permission to complete the adoption. Both agreed.

Mark and Tina said yes, too, grateful for the opportunity to keep their promise to Becca. But they continued to grapple with grief and anger that the Indiana Department of Child Services had not done more.

No one from the state would explain how Becca had been left unsupervised long enough to take her own life. Her death didn’t appear in the agency’s annual report on children who die as a result of abuse or neglect. From the outside, it felt as though no one was held accountable.

The Indiana Department of Child Services declined USA TODAY’s request for an interview.

Records obtained by USA TODAY show the state agency cited one of the Damar workers for neglect relating to Becca’s death. Despite her documented mental health history, the worker had left Becca alone for more than 20 minutes – twice the time allowed under guidelines in place at the time for Damar’s Children's Neuro-Psychiatric Crisis Center Unit, records show.

Jim Dalton, the president and CEO of Damar Services, said Becca’s death was “the most devastating thing that’s ever happened to Damar and our Damar family.” He said the organization immediately instituted changes after she died, including removing doors and lockers from rooms, adding another layer of employee supervision and limiting patients’ private time to three minutes in the bathroom or five minutes while sleeping.

“We understand the responsibility that we have every day, and we understand the responsibility we had for Becca that day,” Dalton said. “We continue to be saddened by it. It’s changed our lives forever.”

Mark and Tina couldn’t help but wonder if things would have turned out differently if child welfare officials had more quickly agreed to provide comprehensive services for Becca.

“What would today be like if she'd gotten the help we’d told everyone who would listen she needed two years ago? One year ago? Even eight months ago?” Tina wrote in an emotional Facebook post on Dec. 18, 2019, the day of the adoption hearing.

The system failed Becca, Tina wrote. But she and Mark would not.

Everything they brought to the adoption hearing was in honor of the little girl who could not be there.

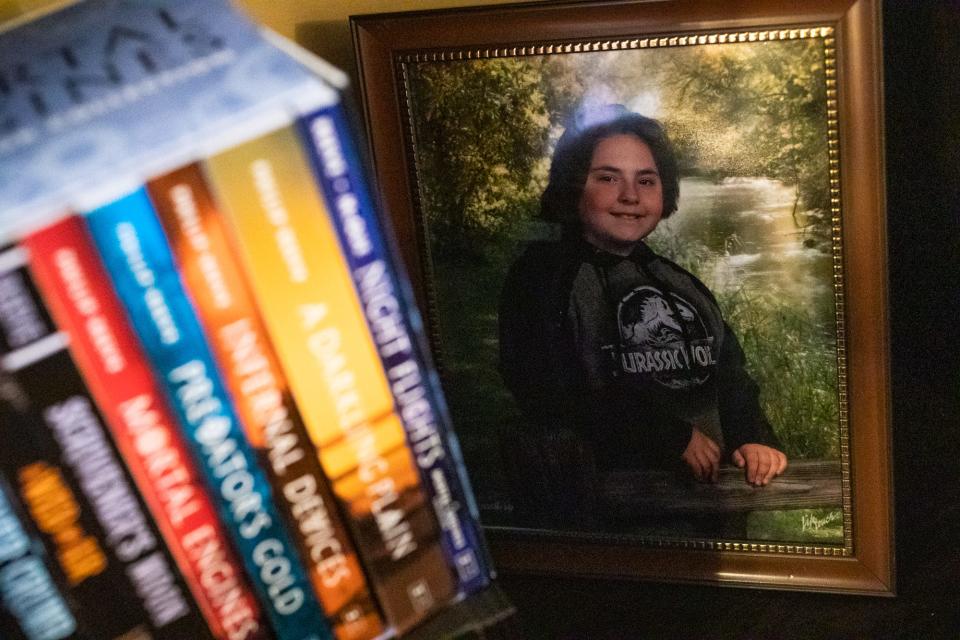

Tina wore a gray sweatshirt with a picture of Totoro, Becca’s favorite anime character. She brought photos that she felt best represented Becca’s vibrant personality – her beaming face in sunglasses, Becca wearing a Batman mask and posing with a shark. And, of course, a photo of Mark, Tina and Becca together.

Inside the Hamilton County courtroom, Tina lined up the picture frames on one of the wooden tables in front of the judge.

Judge Pro-Tem Valorie Hahn, who presided over Becca’s adoption, found herself holding back tears.

“It’s really heartbreaking listening to her struggles and how much this family fought for her,” she said. “And that just leaves a lasting impression on you.”

Mark and Tina’s attorney asked them to share Becca’s story and to explain why they were there.

We made a promise, and we’re keeping it, the couple replied.

Becca’s best friend, Samantha, wearing a silvery gray headband that had once been Becca’s, spoke about their relationship and about Becca’s wish to be adopted.

Hahn signed the adoption decree and posed with Mark, Tina, Haymaker, Samantha and others, holding the framed images.

Finally, Becca was legally theirs. But it was bittersweet. She was still gone.

“It’s like taking just a piece of your heart and crushing it and trying to push it back into the rest of the heart,” Tina said. “You can’t do that.”

‘A chance to grow’

Becca was a bundle of energy throughout her short life, Mark and Tina said. She rarely sat still.

So when Tina read on Facebook about a company selling kits to plant a tree with a loved one’s remains, it felt right. Becca loved being outside. And trees are full of life. They age. They sway in the breeze.

“She would have a chance to grow,” Tina said.

Becca’s tree was planted on the grounds of the Girl Scouts’ Camp Dellwood. Her friends and family drive by from time to time, or they stop to visit.

“It’s probably the best way we can continue to remember her is through a group of unrelated people who loved her,” said Alicia Burkholder, the leader of Becca’s Girl Scout troop and the mother of Samantha. “It kind of speaks to who she was. You didn’t have to be biologically related to her. You were family, and that's how she rolled.”

In the nearly three years since Becca’s death, her tree has grown taller than Mark and Tina. On a recent spring day, the sun glinted off its green leaves. Its branches stretched toward the sky.

Contributing: USA TODAY senior data reporter Aleszu Bajak

Marisa Kwiatkowski is a reporter on the USA TODAY investigations team, focusing primarily on children and social services. Contact her at mkwiatko@usatoday.com, @byMarisaK or by phone, Signal or WhatsApp at (317) 207-2855.

More in this series

‘A broken system’ leaves tens of thousands of adoptees without families, homes

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Grieving foster parents keep promise to adopt daughter