Don’t have insurance? Your hospital stay might be short

Editor's Note: The following is part of a class project originally initiated in the classroom of Ball State University professor Adam Kuban in fall 2021. Kuban continued the project this spring semester, challenging his students to find sustainability efforts in the Muncie area and pitch their ideas to Deanna Watson, editor of The Star Press, Journal & Courier and Pal-Item. This spring, stories related to health care will be featured.

MUNCIE, Ind. – Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, U.S. hospitalizations have risen dramatically.

According to the weekly hospitalization tracker by John Hopkins University, there was an increase of Indiana inpatient beds being occupied by COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients in January 2022, with 80% of the beds being occupied. However, a patient's insurance coverage can affect the length of their hospital stay and health outcomes.

As of 2021, Medicaid insures 21.6% of Hoosiers under the age of 65, while 8.8% are uninsured, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. But a 2016 study in the medical journal "The American Surgeon" found that “insurance status strongly associates with hospital [length of stay] after trauma" with the uninsured spending fewer days in the hospital as compared to those with private insurance, and those with public insurance, such as Medicare and Medicaid, were "experiencing extended stays."

"A lot of times the uninsured may or may not have an advocate," said Glynnis Dear, office manager of Walker Medical LLC, a professional limited liability company with specialization in pediatric and young adult medicine. "If it is an indigent patient, their hospital stay can be shorter. If they have state-funded insurance, [hospitals] are pretty good at keeping the patient. But it is known that [the hospital] will release you earlier if you're not critically ill."

Indigent patients are those who cannot afford the medical care they receive on top of their living expenses, Dear explained.

"Certainly, we've done a much better job in the last 10 years of reducing the amount of people with no insurance at all," said Kevin Gatzlaff, associate professor of insurance at Ball State University. "Any hospital that takes Medicare has to provide treatment without regard to the ability to pay."

That's due to the Emergency Medical Treatment & Labor Act passed by Congress in 1986.

According to the Indiana Department of Insurance, "Most people age 65 or older are eligible for Medicare Part A (Hospital Insurance) based on their own employment or their spouse's employment." Part A coverage includes services from inpatient hospital care to operating and recovery room costs.

For those who qualify for Medicaid or the "Healthy Indiana Plan," or HIP, patients receive coverage for hospital stays. Still, they are required to pay a copayment every time they "receive a health care service such as going to the doctor, filling a prescription or staying in the hospital."

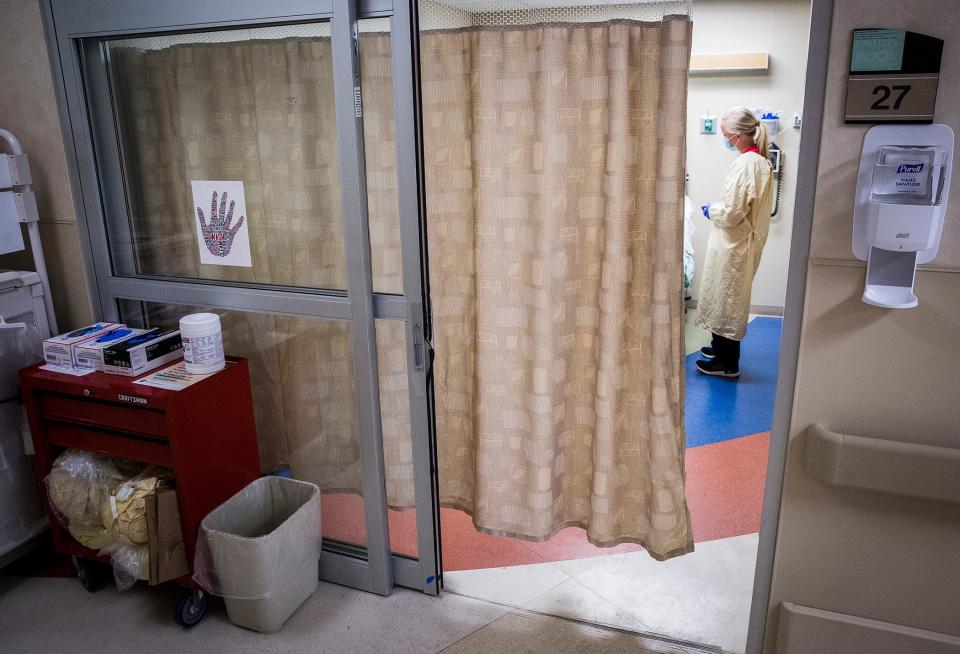

However, a patient's ability to pay could affect the quality of care they receive at a hospital.

According to a study published in 2021 by “BMC Health Services Research,” "Low-income patients tend to experience worse health quality and delayed diagnosis and treatment, leading to worse health conditions when they are forced to seek health care."

Dear explained when patients are released prematurely, their likelihood of returning to the hospital increases.

"You run the risk of reinjury. You run the risk of symptoms becoming worse," said Dear.

"Everything dealing with Medicare and Medicaid — even general patients are numbers; they are codes," said Esther Cummings, retired insurance verifier and financial counselor at Methodist Hospital Northlake. She worked in the hospital system for 25 years.

What Cummings is referring to is called medical coding.

For example, a patient is admitted into the hospital for contracting influenza but also has pre-existing condition such as arthritis. Both of those conditions would be entered into the hospital’s medical system as alphanumeric codes for documentation and medical billing purposes. Patients and insurance companies can be charged based on those codes, Cummings explained.

"The more codes you have on a person, the longer they can stay in the hospital. That can be a determining factor as well," she said.

Gatzlaff believes patients' reliance on the government may not be as great as people think.

"That's the risky take; the more you rely on insurance, the more you rely on government. There's going to be more distance between the doctor and the patient," Gatzlaff said.

This article originally appeared on Muncie Star Press: Don’t have insurance? Your hospital stay might be short