Fentanyl killed former college pitcher. Now his brother is helping others get sober

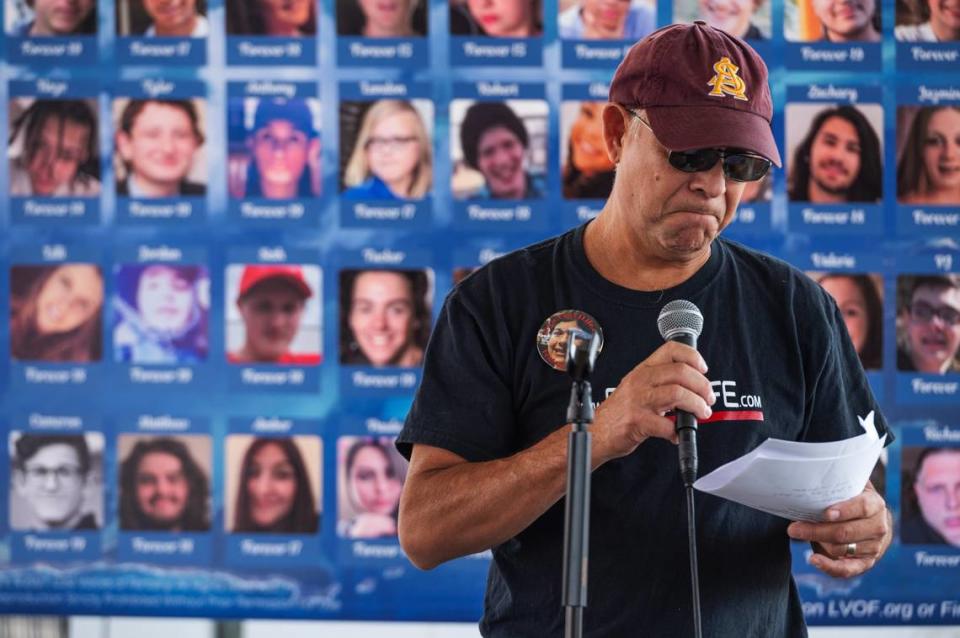

James Hill stood before a crowd of roughly 200 people in downtown Leavenworth in September and pointed to a nearby area.

“On May 30, 2018, they found my baby brother dead right there in that bathroom,” Hill said as he stood on stage at Haymarket Square for a rally to raise awareness about the dangers of fentanyl. “They actually drove my brother from a house over here to that bathroom.”

Geoffrey “David” Hill — a former Western Illinois University baseball player who once aspired to be in the big leagues — was 29 years old when he died of a fentanyl overdose.

Other than in rehab, Hill hadn’t really told his story of addiction or detailed what had happened to the brother he said was “just a good kid” and a “very loving guy.”

James, who for years was addicted to pain pills and also used methamphetamine and heroin, said from the stage that after his brother died, he got clean. And his hope, his reason for speaking out, is that someone will hear about David and others whose lives were taken way too soon from fentanyl and stop using.

“Sometimes I was in and out of county jail, prison,” said Hill, admittedly nervous in this first big public speaking moment. “I’ve got about 10 years of county jail and prison involved in this. But I’ve been sober for 40 months.”

The crowd — filled with parents and family and friends of people, especially teens, who died because of fentanyl — erupted with applause.

In 2018, about three or four months before his brother died, Hill himself had overdosed on fentanyl — which he said he didn’t know he had taken — and was rushed to a hospital.

“We thought we were buying heroin but fentanyl was in the heroin,” Hill said. “The hospital Narcanned me. They Narcanned me three times.”

Narcan is a medicine that rapidly reverses the effects of fentanyl.

Soon after he overdosed, Hill said from jail he called his dad and brother, who were both using pain pills and heroin at the time.

“I said, ‘You guys need to stop doing that s–-t now, because I literally just died. I’m lucky to even be here calling you guys.’”

Neither, he said, heeded the warning.

From promising baseball career to addiction

David had been using drugs for several years when he died, Hill told The Star. But that wasn’t the life he was destined to have.

“My brother never missed a day of school until senior skip day,” Hill said. “And he even felt bad for that. My brother was on the honor roll every year. … My brother liked to talk to people if they were down and out, try to bring them up.”

At almost 6 feet, 7 inches tall and anywhere from 220 to 280 pounds, David was a “big gentle giant,” his brother said. And on the baseball mound, as a right-handed pitcher, he thrived.

First in his hometown. David started playing ball at age 3, according to his obituary. He played for many town teams and traveled with others.

“He would play any position asked of him,” the obituary said.

In 2010, his senior year at Western Illinois, he led the Leathernecks with two saves and didn’t allow an earned run in his first five outings, according to the university’s online roster for that year.

But at some point, after a tragedy involving a cousin and her family, David left college and returned home to Leavenworth to support relatives.

“And he got stuck,” Hill said.

It began with the pain pills their dad was prescribed.

“Started with Percocet,” Hill said. “And then you know the doctors they just move you up and then it goes to oxycodone 30s. And then it’s like, ‘OK, well eating them’s not working, I’ll snort them. Snorting them’s not working, I’ll try a needle.’ And after that needle, you’re in all the way.

“And it goes from pain pills to heroin. We didn’t do meth for a long time. But then when we do meth, when we’re coming down from meth, our addiction for stuff on the downers just got like turbo mode.”

He knew David would often struggle mentally.

“My brother was one of the ones where he wanted to resolve other people’s problems and issues before his own,” he said.

The night David died — which was in the early days of the fentanyl epidemic here in the Kansas City area — Hill said their dad gave David money to buy heroin and then David told him who he was going to get it from. Hill said he knows that David, who adamantly stayed away from fentanyl, didn’t know he was getting something laced with it.

“My brother’s story is more along the line of we don’t know what we’re getting out there,” Hill said. “You don’t know what you’re getting.”

‘Asked God for forgiveness’

For a long time after David’s death, Hill said he lived with guilt — “I was the first one to put a needle in his arm.”

But he’s been working through that and said he feels at peace.

“I’ve done asked for forgiveness,” he said. “I’ve asked God for forgiveness on it.”

Now he wants to do whatever he can to keep other young people from turning to drugs. Maybe, he said, he can keep one kid from taking pills or other drugs. For David.

In the past year he’s heard about other fentanyl deaths in Leavenworth County. Three teens whose families believe they didn’t know they were taking fentanyl, but thought they were buying pills for a quick high.

Hill began talking with Andy Burris, the father of Nicholas “Cruz” Burris, 15, who died in January.

For Burris, it was crucial to show young people through Hill’s testimony that there is a way out of addiction. It’s why he wanted him to speak at the September rally.

“According to James, it was his brother dying from fentanyl that kind of woke him up,” Burris said. “I just want people to understand that if they are addicted, there is hope that they could overcome their disease.”

If Hill could, he’d tell his brother “that I love him and that sobriety is a better way,” Hill said. “I mean, I know he sees how I’m living.”

At the recent rally in Leavenworth, those attending marched down several downtown streets like Fifth and Seventh, Delaware and Shawnee.

“What do we want?” Shannon Earnshaw asked through a bullhorn. Shannon’s son Shawn Dewey II, of Edwardsville, died last year after buying pills his mother said she believes he hoped would help with his insomnia.

“Justice!”

“When do we want it?” Earnshaw asked.

“Now!”

“Who do we want it for?”

“Our children.”

Earnshaw waited to talk with Hill after the event. She wanted to thank him.

“I just think he’s so brave, to stand up, you know, and tell the other side of things,” she said. “He’s been affected by losing a family member, being addicted … and he’s went through something that a lot of these people that die don’t get to do.

“He’s been through the fighting to get off of it and now he’s taking a stand and sharing his message.”

During Hill’s testimony that day, he told the families and friends of people who have died from fentanyl that “this right here is the most beautiful place on this earth to be right now.”

“This needs to be happening everywhere,” Hill said. “Not just the United States, not just Kansas, but across the world. It starts with us.”

Before he stepped down from the stage, he quoted the song “Drug Addiction” by hip-hop artist Colicchie, saying that the “young people we’ve lost and the grown-ups that we lost” to fentanyl will never be able to say these words.

“‘My pain’s deep, I have been through hell. … I managed to survive. I got a story to tell,’” Hill said.

“And that’s why I do this. If I can’t spread (the story), I can’t save nobody.”