Don’t try to fix James Bond’s onscreen bigotry – just live and let it die

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

If James Bond wants his licence to kill on screen renewed, changes may be in order. The days when 007 could casually hand a fistful of cash to an Indian man and tell him “That’ll keep you in curry for a few weeks,” as he did in 1983’s Octopussy, are clearly over. He’s not going to get away with beating up women, either, as he does in any number of films from GoldenEye to From Russia with Love. Websites have compiled incriminating lists of Bond’s crimes against political correctness – and the rap sheet is very long indeed.

Bond’s producers are well aware that his behaviour in the Sixties and Seventies won’t fly in the 2020s. It emerged this week that Ian Fleming’s Bond novels (like those of Roald Dahl) are already being reworked for modern readers. The Daily Telegraph reports that “terms and attitudes which might be considered offensive today” are being cut out of the text. Some racist language has been deleted.

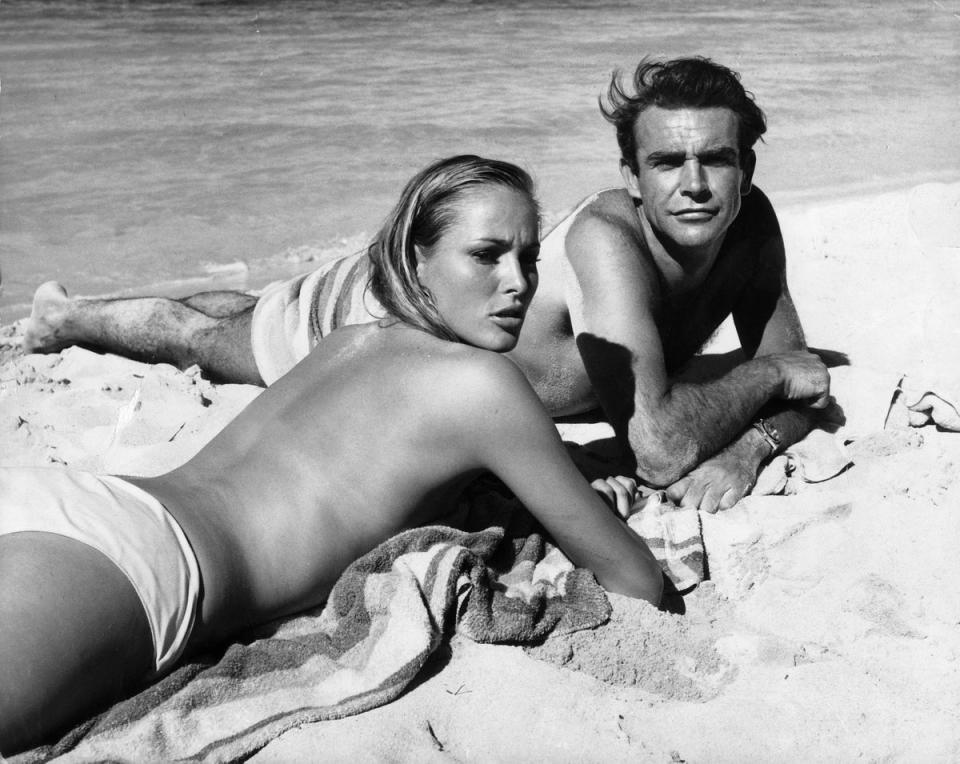

If the books are being updated to reflect modern sensibilities, should the films get the same treatment? After all, the Bond production team has always insisted that the character portrayed on screen, whether played by Sean Connery, Pierce Brosnan or Daniel Craig, is very close to the “quiet, hard, ruthless, sardonic, fatalistic” secret agent dreamed up by Fleming one sunny morning in Jamaica in 1952.

Whatever flaws Bond has on the page, he shares in the film adaptations. Is it enough, then, to treat his more boorish behaviour in the same way we might treat the antics of a drunken uncle at a wedding, and ignore it? Or should we hold him to account for his historic delinquencies, and clean up the movies retrospectively?

There is a sense that both sides in this debate are getting into an unholy pickle. In recent days, Bond fans have been working themselves up into a rage over amendments to the novels that appear, actually, to have been made years ago. It has been widely reported, for example, that lines in Fleming’s 1954 novel Live and Let Die, describing patrons in a Harlem nightclub as “grunting like pigs at a trough”, have now been changed to the blander, less offensive: “Bond could sense the electric tension in the room.” In fact, in a 1987 paperback edition of the book, the “pigs at a trough” line had already vanished, and the “electric tension” sentence was in place even then.

It is also apparent that amendments made by “sensitivity readers” to the odd phrase won’t change the overall thrust of Fleming’s storytelling at all. Multiple references to “the sweet tang of rape”, as well as derogatory remarks about Asian people, are set to remain in the novels – which suggests that the latest edit was a bit of a half-baked job in the first place.

This summer marks 50 years since the release of the film adaptation of Live and Let Die (1973), Roger Moore’s debut as 007. Directed by the patrician white English filmmaker Guy Hamilton, it shamelessly filches ideas and motifs from Blaxploitation movies of the time, notably Shaft (1971). The villains are Black drug dealers led by Mr Big/Dr Kananga (Yaphet Kotto), one of the most powerful criminals in the world, cooking up a plot to flood the US with heroin. He also doubles as the Idi Amin-like dictator of a Caribbean island.

Almost all the Black characters are demonised or caricatured. The film opens at a funeral in New Orleans, where British MI6 agents are murdered by Dixieland-jazz-loving Black mourners and snake-wielding Voodoo witch doctors.

Early Bond-era movies, even the classics, are rife with equally troubling details. In some cases, small changes have been made to make similarly awkward and aggravating older pictures more palatable for modern audiences. For example, in some versions of 1955 British war film The Dam Busters, the racially offensive name of Wing Commander Guy Gibson’s black Labrador, which is also the code for the secret RAF Bomber Command mission, is cut out. And in recent years, when The Dam Busters has been shown in its original form, viewers were given a warning that it contains a term they’re very likely to find offensive.

In other cases, films with similar sensitivity issues are shunted to the margins by broadcasters and distributors. A prime example is Gone with the Wind, which was briefly removed from HBO Max in 2020 and hasn’t been shown on the BBC since 2007. This is a multi-Oscar-winning Hollywood classic, set during the American civil war.

It’s world-famous; no one can forget Rhett Butler (Clark Gable) telling tearful Southern belle Scarlett O’Hara (Vivien Leigh): “Frankly, my dear, I don’t give a damn.” That being said, the picture wouldn’t be made today. There is simply no way to disguise the racist attitudes of its white Southern heroes, or to overlook the film’s denial of the horrors of slavery.

“It’s a film that glorifies a system of brutality. It is a film that really showcases a kind of racist ideology that was tied to the Confederate regime,” film historian Jacqueline Stewart, a writer on Black cinema who provided a new introduction to the film after it was reinstated on HBO, told NPR. If you know that going in, you probably won’t want to watch the movie.

This is the paradox. If you add introductions that contextualise a film, or provide trigger warnings, it’s as if you’re holding it up with a pair of tongs. You may be trying to make it more watchable for contemporary audiences, but you’re almost certainly putting them off.

When confronted with problematic, older pictures, the British Board of Film Classification (BBFC) tends to respond by changing its ratings. “Once content is resubmitted to the BBFC, it is viewed against our current classification guidelines,” a spokesperson told The Independent, explaining how the organisation is continually reviewing and reclassifying previously classified content to reflect current sensitivities. The BBFC can’t ask the long-deceased DW Griffith to re-edit his racist 1916 civil war silent epic The Birth of a Nation, but it can slap a “15” certificate on it, instead of an all-ages “U”. This means viewers will immediately recognise that the film must have issues.

Audiences watching Bond adventures are surely savvy enough to see the racist and sexist parts for what they are

Fans of Bond and Dahl will likely be furious if, in the coming months, some jobsworth censor decides, say, to cut out the Oompa Loompas from Tim Burton’s version of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory on the grounds that they’re too small and silly, or to edit From Russia with Love to replace Bond’s martinis with non-alcoholic beverages. Everyone knows that Bond is a womaniser, a licensed killer with a healthy thirst, and that he likes gadgets and Aston Martins. Trying to sanitise him would be pointless. Nor does it make any sense to strip out the cruel surrealism that has always distinguished the best screen adaptations of Dahl’s stories.

It is possible, though, to respect the writers’ visions, enjoy the cinema versions of their works, and still question their worldviews. In the cases of both Bond and Dahl, the movies are full of such self-mocking, ironic [and very British] humour that it’s hard to take them too seriously anyway. The jokes keep the obnoxiousness at bay.

Regardless, these films are far too popular to be hidden away like old Benny Hill comedies from the Seventies. They’ve remained in constant circulation since they first appeared in cinemas. I spoke recently with German filmmaker Nora Fingscheidt (director of Sandra Bullock vehicle The Unforgivable), whose fond memories of Goldfinger were shattered when she rewatched the film with her 10-year-old son. She was startled by the savage treatment of its female characters. “From a gender perspective, that’s almost unwatchable with a child, because you have to explain so much how society has changed,” she concluded.

There is nothing quaint about misogyny, but Goldfinger is arch and cartoonish. Audiences watching Bond adventures are surely savvy enough to see the racist and sexist parts for what they are: a reflection of the era in which they were made. With or without the help of parents, kids would likely be able to see their absurdities for themselves, which is why the scissorhands should leave past versions of 007 well alone.

That’s not to say there isn’t room for improvement. Daniel Craig’s interpretation of Bond was notably far more nuanced and sensitive than that of his predecessors. It would be a major surprise if his successor isn’t in a similar touchy feely groove, at least when he or she isn’t busy killing enemy agents. In this ever-changing world in which we’re living, maybe Bond should be allowed to live twice.