Donald Trump, Bill Clinton and the Naughty '90s

Close

Two decades ago, on a frigid night just before the New Hampshire presidential primary, America first met Bill and Hillary Clinton as a couple.

It was January 26, 1992, a drowsier time when daily papers controlled the narrative of presidential campaigns; when CNN was the only cable news network on the air, and blogs didn’t exist. Bill Clinton was the favorite to win the Democratic nomination and face President George H.W. Bush in November.

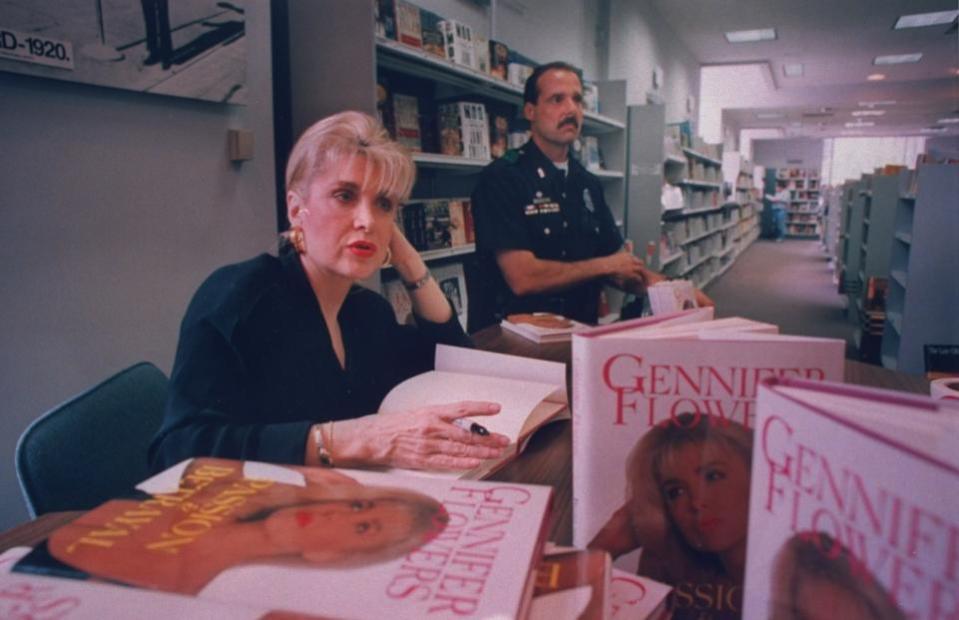

And then he had what a chief adviser of his would come to call a catastrophic “bimbo eruption.” Her name was Gennifer Flowers, and the Star, the supermarket tabloid, was about to publish a story saying that she and Clinton had had a 12-year affair. In response, the first couple of Arkansas had agreed to a do an emergency interview with Steve Kroft of 60 Minutes, to talk about their marriage. The Arkansas governor and his wife insisted on appearing together, and it was her words, more than his, that saved his candidacy.

The Clintons sat beside each other on a couch: Bill, in a suit, with his hands almost prayer-like between his knees, and Hillary, with her arm draped on his back or straying occasionally to settle on his arms. She wore a thin black headband and a turquoise suit with matching turtleneck and eye shadow. From time to time, she examined her husband lovingly, yet maintained a commanding air, nodding approvingly as he spoke, then jumping in as necessary.

Her husband’s responses to Kroft’s questions were measured, firm and softly delivered. At some points, a viewer couldn’t help thinking that he was a nimble actor, patting his heart and leaning forward. Now and again, he appeared hurt, even vaguely aghast, his bottom lip resolutely chewed or his eyebrows gone all circumflex. Other times, he shook his head or narrowed his eyes to express exasperation with his interrogator.

KROFT: You’ve said that your marriage has had problems…. What do you mean by that?

CLINTON: I think the American people, at least people that have been married a long time, know what it means and know the whole range of things it can mean.

KROFT: Are you prepared tonight to say that you’ve never had an extramarital affair?

CLINTON: I’m not prepared tonight to say that any married couple should ever discuss that with anyone but themselves.... And I think what the press has to decide is: Are we going to engage in a game of “gotcha”?

Finally, Kroft tried to articulate what many viewers were thinking: “I think most Americans would agree that it’s very admirable that you’ve stayed together—that you’ve worked your problems out, that you’ve seemed to reach some sort of understanding and an arrangement.”

“I wanted to slug him,” Bill Clinton would later concede in his autobiography, My Life. Here he was—alongside the woman he’d admittedly aggrieved, her hand on his forearm. “Instead, I said, ‘Wait a minute. You’re looking at two people who love each other. This is not an arrangement or an understanding. This is a marriage.’”

Hillary pounced, and her cool-headed response was the reverberating sound bite: “You know, I’m not sitting here, some little woman standing by my man, like Tammy Wynette. I’m sitting here because I love him, I respect him, and I honor what he’s been through and what we’ve been through together. And, you know, if that’s not enough for people—then, heck, don’t vote for him.”

Then, in a portion of the segment that was never broadcast, the overhead lights that had been set up somehow became unmoored, along with their wood-beam mount. The rigging toppled over, with a clamber, barely missing Hillary. “They just kind of popped off,” Kroft remembers, “and came crashing down on the back of the sofa behind the Clintons, and it knocked over a pitcher of water, and they lurched forward [to avoid the] burning filaments and flying glass.”

A tragedy averted, Bill Clinton took his wife in his arms, clutched her close, and kept telling her, softly, that he loved her—that everything would be OK. The couple would be fine, but the interview—and Clinton’s presidency—marked the beginning of a seismic shift in American culture, which led to much of what we abhor about the present day.

Sex, Voyeurism and Reality TV

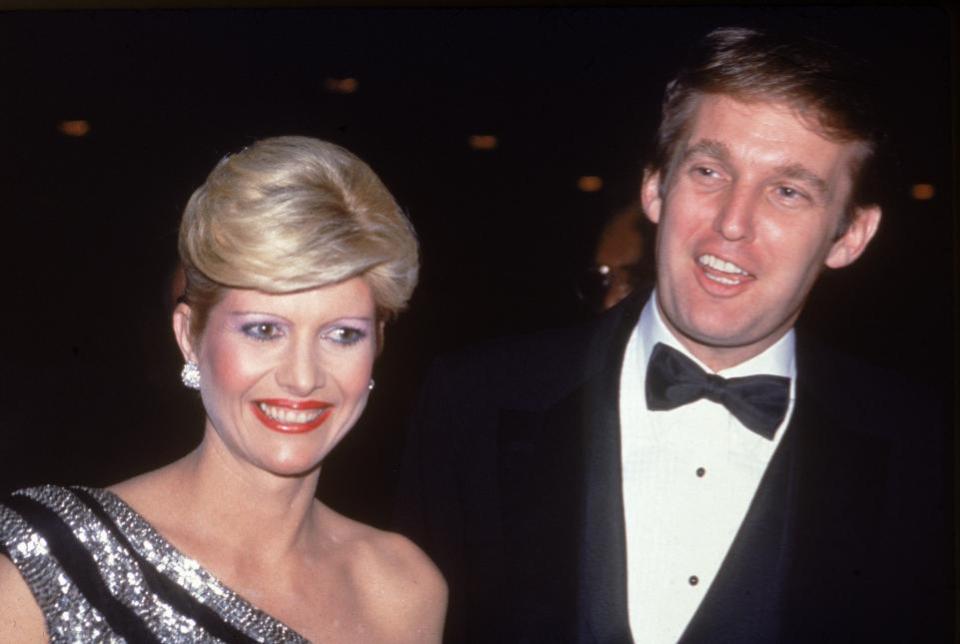

The shame-strafed 1990s began two years before that infamous interview, with a blaring tabloid headline in the New York Post : “Best Sex I’ve Ever Had.” The story was about real estate mogul Donald Trump and his lover, Marla Maples—she was supposedly talking about his prowess in the bedroom. This was well before Trump’s career as a reality-TV star (though he had already boasted that he could become president).

The decade ended on the eve of the 2000 election with Americans in suspended agitation. They were doubtful that presidential hopeful Al Gore could emerge from the shadow of yet another Bill Clinton extramarital relationship (this one with White House intern Monica Lewinsky) and his subsequent impeachment (he couldn’t). They also hoped that our computer programs could avoid a global Y2K meltdown (they did, even though many tech fortunes would evaporate a few months later with the end of the dot-com bubble).

In between those events, it was much ado about Clinton, the man whose time in office perfectly captured the rapid changes taking place in American culture during the 1990s—the voyeurism and virulence aroused by social media; the thirst for scandal incited by 24/7 tabloid news; the false narratives concocted by reality TV; the breakdown of private barriers (as a result of the World Wide Web); the tacit permission to lie about unethical conduct; and the partisan rancor perpetuated by the culture war.

This was the decade when Americans, as never before, confronted an expanding public encroachment on their personal lives. They were entertained and alarmed by tales of well-known figures ensnared in scandal. They grappled with matters surrounding sexuality, the web and nascent social media. Sex moved to the forefront of their lives—from the creation of Viagra and the growth of internet porn to the sometimes venomous backlash against both.

Today, a generation after Bill Clinton was sworn in as president, promising “American renewal,” it’s no coincidence that we have ended up with President Trump promising “this American carnage stops here.…” Clinton’s naughty ’90s led to the prevaricating age of George W. Bush (remember “Mission Accomplished”? The search for Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction?). Taken together, those 16 years created an environment in which, after two relatively scandal-free terms of Barack Obama, a divided America, accustomed to i ts own version s of faux reality, chose Trump, a serial untruth-teller as president—a man whom many voters felt they knew because of his role on a reality-TV show.

‘You Ate Good Pussy’

In early 1992, after Bill and Hillary Clinton appeared on 60 Minutes, many voters admired their unflinching commitment to each other. But at least one TV viewer was aghast. “I was seething with outrage,” Flowers would recount in her memoir, Passion and Betrayal . “To watch the two of them sit there with innocent looks on their faces, lying to the entire country, was infuriating.”

The night after the interview, Flowers showed up at a packed press conference at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria. The media free-for-all—350 people by one Clinton campaign estimate, with CNN covering the proceedings live—represented a nadir in real-time television news. Flowers wore a bright honeysuckle suit with black lapels and some majorly ’80s shoulder pads. Her lips were full and red and almost cartoonishly solemn. Her pyrotechnic blondeness, with its cascade of dark roots, wreathed her face like a spray of goldenrod. “The truth is I loved him,” she said. “Now he tells me to deny it. Well, I’m sick of all the deceit, and I’m sick of all the lies.”

She had the tapes to prove it too. In one snippet, she and Clinton talked about what she might say if reporters asked about the rumored affair; what she recalled with a naughty laugh was that she would tell them, “You ate good pussy.” Later, Clinton seemed to be urging Flowers to deny what sounded very much like an affair. “If they ever hit you with it, just say ‘no’ and go on.… If everybody sort of hangs tough, they’re just not going to do anything.… They can’t, on a story like this…if they don’t have pictures.”

The press conference soon devolved from farce to vaudeville. One reporter asked if Flowers would “be so kind as to elaborate on the sex and the relationship you say you had with him over 12 years? We want you to talk about it. That’s why the cameras are all here.” (Flowers declined, telling her to read the Star .)

As the crowd continued to fire off questions, one man distinguished himself from his peers— “Stuttering John” Melendez, a fixture on the Howard Stern radio show who’d made his name by finagling his way into the path of celebrities and ambushing them with comically confrontational queries. “Did Governor Clinton use a condom?” he asked, straight-faced.

At once, it became clear that the retaining wall between news and entertainment had collapsed. And now a mock reporter appeared, using tabloid language to lampoon the press, politicians and their pieties.

Stuttering John’s follow-up question was more outrageous: “Will you be sleeping with any other presidential candidates?”

His one-liners underscored why the press pack was there in the first place. This was the dawn of the sex-scandal lynch mob. They had come to listen in on what they normally wouldn’t hear. They had come to see for themselves what Bill Clinton might have seen in Flowers. And they had come, cheeky devils, to be in the same room with a woman lusty enough to charm a governor—and crafty enough to switch on a tape player.

Flowers had merely whetted their appetite. They would soon be salivating for more.

The Great American Sex Tape

Some time in the mid-’90s, American decorum disappeared. The media began to pay far more attention to the disgrace of others. And if there was a tipping point, it may well have been May 6, 1994, the day Paula Jones filed a civil lawsuit against Bill Clinton, alleging that he had made an insulting sexual proposition to her while he was the governor of Arkansas—and later defamed her. (Clinton would deny the charges.)

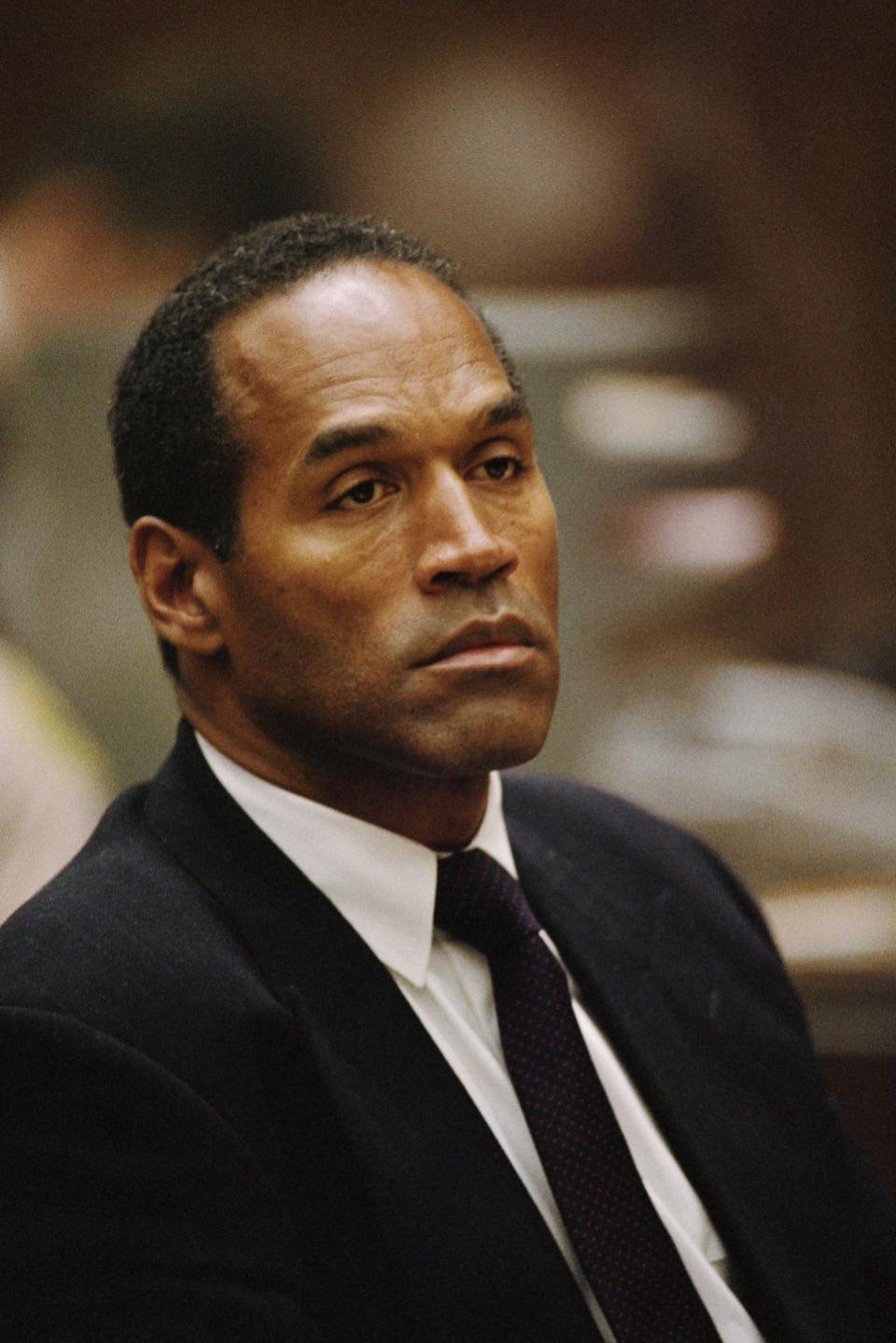

A month later, on June 17, a television audience of nearly 100 million watched what’s now considered one of the first real-life reality-TV shows: a phalanx of police cars pursuing former NFL star O.J. Simpson in his white Ford Bronco, days after the stabbing deaths of his wife and her male companion. Simpson’s subsequent trial would dominate national headlines for more than a year.

The Jones and Simpson cases signaled a massive cultural shift. Earlier in the century—especially in the conservative Eisenhower years—Americans, as a rule, had tried to modulate many of their baser instincts. Upon encountering a humiliating real-life circumstance, they may have been automatically drawn to it, but they were simultaneously repulsed.

No more. By the mid-’90s, with the rise of the media’s tabloid fixation, 24/7 news and the internet, our dominant impulse was to unapologetically eavesdrop, to leer, to pry into the private affairs of others, particularly those of famous people, whose hunger for celebrity seemed to somehow justify our intrusion. The decision by many in the media—in a competitive, attention-fractured and economically challenging marketplace—to turn every alleged wrongdoing into another excuse for spectacle helped news consumers accept and then expect explicit details about embarrassing, sexually compromising or criminal events.

Many of those events stand out—from the Simpson trial to “the wife with the knife,” Lorena Bobbitt, who cut off her husband’s penis in 1993 after she says he raped her (he denied it). But one incident speaks most clearly to the collision of celebrity media, sex and voyeurism, and foreshadowed how the internet would play such a paramount part in our everyday existence.

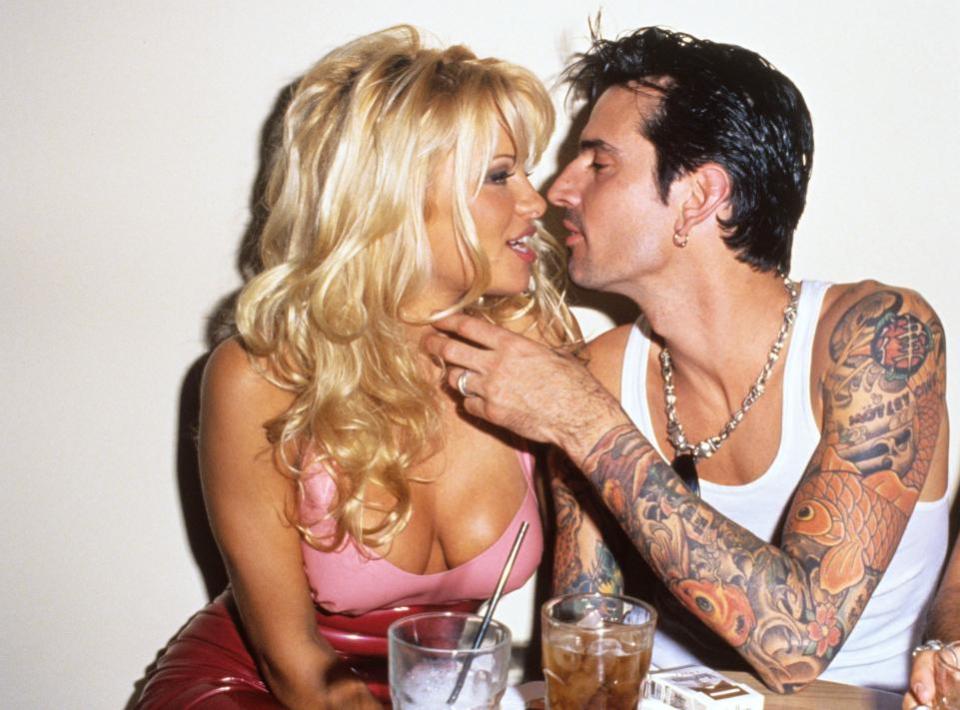

In late October 1995, a disgruntled handyman (and sometimes porn actor) named Rand Gauthier reportedly stole a locked Browning safe from the Malibu home of the buxom Baywatch star Pamela Anderson and her husband, Tommy Lee, the heavily tattooed drummer of the heavy metal band Mötley Crüe . The contents included a home video showing the recently married couple in various states of connubial union. Somehow that footage was then duplicated, packaged and sold off. Despite the lawsuits that followed, an internet porn mogul acquired a copy of the pirated tape and marketed it as a triple-X film.

Millions watched it. The video eventually became the Citizen Kane of celebrity sex tapes. And people all over the world—some of whom had never before felt compelled to watch porn—or use the internet, were eager to watch online. As the writer Pamela Paul put it in her 2005 book, Pornofied : “[This] landmark pornographic home video is credited with bringing more users online than any other single event.”

This celebrity sex tape scandal wasn’t the first of its kind (that belonged to actor Rob Lowe, who in 1988 filmed an encounter with two young women, one of them a minor). But it was shocking because it was explicit, it was off-limits—clearly intended for the couple’s private consumption—and it was among the earliest videos to show famous people getting it on, and at considerable length.

The reach of the purloined video was immense. Before the end of the decade, according to The Wall Street Journal , a not-insignificant percentage of the internet’s tens of millions of webpages (many of them not related to porn) would be meta-tagged with the words “Pam” or “Pamela” or SexTape”—as the site’s owners were hoping to draw residual clicks, gelt by association. Since the tape was released, a bevy of purloined sex tapes have followed—including those with Paris Hilton, Kim Kardashian and Kendra Wilkinson—all of whom became reality-TV stars. (It wouldn’t be until 2017, however, that major media outlets would speculate about a phantom, and likely bogus, sex tape involving the president of the United States.)

By the mid-’90s, the web had become the world’s masturbation mecca and the epicenter of the culture wars.

Electile Dysfunction

America’s rabid, hyperpartisan divide began in the early ’90s—and it was mostly about sex. Pop culture had become crude. Pornography was rampant. Casual sexual encounters were more prevalent and less stigmatized. There was a major upsurge in cases of sexually transmitted diseases. And “the divorce rate remains, stubbornly, one in two,” journalist Joe Klein wrote in a 1992 Newsweek cover story: “The out-of-wedlock birth rate has tripled since 1970.… A nauseating buffet of dysfunctions has attended these trends—an explosion in child abuse, crime…name your pathology.”

Neither Democrats nor Republicans celebrated these developments, but Bill and Hillary Clinton happened to be in the left place at the right time. In the seven months between their 60 Minutes appearance and the Republican National Convention, the couple brought animosity against those who would defend one’s right to choose—and one’s right to love whomever one chose. Despite Bill Clinton’s broad appeal, he and his wife, both proud feminists, were being widely vilified. They were the dreaded duo of the 1960s counterculture. Or so said Republicans, evangelicals, right-wing radio hosts, policy journals and secular and religious conservatives.

Whether out of genuine concern or cynical electoral politics, Republicans tried to capitalize on that view, using increasingly harsh rhetoric and aggressive tactics against the Clintons, beginning with the 1992 Republican National Convention in Houston. The gathering was supposed to propel President George H.W. Bush, a moderate Republican, to a second term. But inside and outside the antiquated Astrodome, a far more radical, trash-the-bastards theme had taken hold. Decades before the crowd at the 2016 GOP convention chanted, “Lock her up!” T-shirts at the ’92 Republican confab advised: Blame the Media. Stickers urged: Smile If You Have Had an Affair With Bill Clinton. One placard bore a cannabis logo: Bill Clinton’s Smoking Gun. Another: Woody Allen Is Clinton’s Family Values Adviser.

The virulence went beyond the mordant slogans. Former Nixon speechwriter and ultraconservative commentator Patrick Buchanan had secured nearly a quarter of all Republican support in the primaries. Bush, considered far too moderate for those on his right flank, had been forced to appease Buchanan’s forces or have his convention implode. So to shore up their base, Bush and the GOP mandarins gave over large swaths of the party platform to the hard-liners.

The platform was packed with a slate of provisos related to sexual mores, cultural kashruth and the supremacy of the nuclear family. It sought to ban gay marriage, adoption by gay couples, the sale of porn and public funding that might be used to “subsidize obscenity and blasphemy masquerading as art,” among other things. (Some of those major culture war battles continue to this day over abortion, gay marriage, sexual harassment and assault, domestic abuse and LGBT rights.)

The moderate Republicanism of Bush would struggle to wear two masks—and he wound up losing to Clinton in the general election that fall. And during the new president’s first term, radical GOP insurgents, led in part by Newt Gingrich, inaugurated an era of “hyperbolic partisanship,” according to historian Geoffrey Kabaservice. “It was Mr. Gingrich who pioneered the political dysfunction we still live with…usher[ing] in the present political era of confrontation and obstruction.”

An erudite history buff with a cherubic presence and silvery helmet of hair, Gingrich became a quantum force in American conservatism. During his shining hour—September 27, 1994—he enlisted 367 men and women, all running in that year’s midterm elections, and assembled them as one battalion on the Capitol steps. As the cameras rolled, he made sure each candidate signed a so-called Contract with America. This measure, beyond addressing popular issues such as tax breaks, street crime, an invigorated military and a balanced budget, focused on some of the same culture-war priorities laid out at the 1992 Republican National Convention.

The signing made for great political theater. It also had animated and unified the party. The fact that legions of potential legislators were in lockstep, as historian Steven Gillon has observed, effectively “nationalized 435 local races…turn[ing] the election into a choice between the Republican agenda and the failures of the Clinton administration.”

Gingrich would prevail, helping Republicans making massive gains in Congress. And though he’d eventually overreach, leaving an opening for Clinton to win re-election, the insane, hyperpartisan environment he helped create presaged the Tea Party, the rabid Republican response to Obama and the rise of birtherism and other bloviating buffoonery.

He also had some help.

A Brief History of Right-Wing Slime

Gingrich, Buchanan and other forces on the right received a major boost from a newly resurgent right-wing press—from talk radio’s angry high priest of the right, Rush Limbaugh, to the GOP’s fair-haired hatchet man, David Brock—a journalist who slimed the likes of Anita Hill, the woman who accused Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas of sexual harassment. (He would deny all charges.)

Joining Limbaugh and Brock was the decade’s most transformative conservative voice: Fox News. The right-wing cable network, devised by Rupert Murdoch and developed by Roger Ailes, premiered in 1996. At the time, CNN was being derided on the right as unapologetically leftist; some called it the Clinton News Network.

Ailes formulated Fox during the GOP’s stunning Gingrich-led resurgence. It went on the air as Bill Clinton ran for his second term. And Ailes would prove to be its ideal architect: a TV sage with McLuhanesque instincts; a political strategist who had helped shape hard-right “brands” such as Nixon, Limbaugh and eventually Trump.

Ailes envisioned cable news with a twist. The channel would build its brand on the rancor of the disenfranchised, a public itch for tabloid stories and a moral seething about the Clintons and the culture’s progressive drift. Tempestuous and incestuous (many of its commentators were GOP stars), the channel would become the party’s 24/7 infomercial, a handmaiden of the right’s successes into the next century. All the while the network would advertise itself as politically evenhanded—what Sam Tanenhaus, the conservative historian, would describe as a “sardonic parody (‘fair and balanced’) of a mainstream media [that] it assumes to be rife with contempt.”

The fourth horseman in this posse was Matt Drudge. He grew up as a Beltway boy who delivered The Washington Star , moved to Hollywood, settled into a job managing the trinket shop at the CBS Studio Center and in 1995 started a gossipy email blast. He called his creation the Drudge Report—the first comprehensive online aggregator of opinion, headlines, and celebrity and political poop. For a while, his target audience was the rumorati within Washington, Hollywood and the media. But by June 1997, once AOL started co-hosting his site, Drudge was a webwide phenomenon and a fedora-wearing favorite of American conservatives.

With his web links and gossip droppings, Drudge was a national nemesis and a guilty pleasure. He linked to far-right columns and home pages, some of them borderline batshit—and gave their rants and rumors equal weight with wire-service items. He reported on other reporters’ reporting-in-progress—and got the biggest political news break of the decade—Bill Clinton’s extramarital relationship with Lewinsky, which in turn, would lead to the president’s impeachment.

Limbaugh, Brock, Ailes and Drudge ruled right-wing radio, print, cable and the web. In the ’90s, media types would debate whether the ethical standards of mainstream newsmen and -women applied to bloggers and their ilk. But within a decade, that question was moot. And thanks in part to this quartet of rogues, the dividing lines were ever less distinct between news and rumor, between information and entertainment, between the media’s treatment of one’s public and private behavior.

A clean line can be drawn, attests Tanenhaus, from Drudge in the 1990s to Donald Trump 25 years later. “It all goes back to Drudge in Hollywood,” Tanenhaus says, in an assessment of Trump’s advisers: “From Drudge to the late alt-right news pioneer Andrew Breitbart and then to Steve Bannon, President Trump’s [former] chief strategist. It’s not just the alt-right. It’s alt-politics—outside the two parties, all via sensationalist media.”

Over the course of a generation, as the web and social media gained currency, these new-media, ultraright conspirators were complicit in disseminating rumor, agenda-bent screeds and the long and gnarly anti-Bill-and-Hillary thread—from the slur that they had somehow set up the “murder” of confidant Vince Foster to the loony concoction of the Pizzagate child-sex ring. That blurring of fact and fiction, and the far right’s accusations of a “liberal bias” by a supposedly monolithic mainstream media, led many to see the press, not the politicians, as the problem, despite the bevy of reporters still unearthing legitimate corruption and scandal.

But the damage was done. The definition of truth and facts had become malleable.

The Michael Jordan of Mendacity

In My Life, Bill Clinton finally admitted the obvious: that he had lied. “Six years after my January 1992 appearance on 60 Minutes, I had to give a deposition in the Paula Jones case, and…I acknowledged that, back in the 1970s, I had had a relationship with [Flowers] that I should not have had.”

It wasn’t just the Flowers affair that fit into this lying theme. During his first week in office, Clinton began to formulate a policy about gay and lesbian service members that would later become “don’t ask, don’t tell,” a directive that mandated lying about sex. And in the fallout of his second-term scandal, he had almost lost the presidency by lying under oath about whether he’d had sex.

Yet some Americans weren’t fazed by this pattern. For all the pique and wincing and mincing, this tendency to parse the truth was a Clinton habit, a strategy, an ethical tic—and one that many appeared to be adopting in their own lives.

The lesson of the Watergate scandal of the 1970s had been that the cover‑up—the lie—was always worse than the crime. But modern presidents have long terms and short memories. Clinton and George W. Bush after him would elevate lying into spin art. Over the 16-year span of their back-to-back administrations, truth—as presented by presidents, White House aides, political spinmeisters and media outlets—became rhetorical taffy. News consumers became seasoned skeptics, learning to expect and tolerate a certain level of elastic veracity (a quality the comedian Stephen Colbert later identified as “truthiness”).

Much of this flimflam, of course, predated the 2000s. In his book Fantasyland , Kurt Andersen traces alternate American reality back 500 years. More recently, some form of elastic veracity had been rolled out by Lyndon Johnson’s Vietnam advisers and spokesmen, honed by Nixon and his White House aides during Watergate and fine-tuned by Reagan during the Iran-Contra scandal—all before the pre-eminence of cable news and the internet.

Yet Slick Willie turned out to be the Michael Jordan of this craft: deft, cunning and convincing, a born debater, talker and persuader. He perfected spinning as his default mode at the very moment truthiness was becoming an acceptable response in human interactions of every kind—in the boardroom and the bedroom, on Wall Street and the ballfield (remember the juice-induced Sammy Sosa-Mark McGwire home-run race of 1998?).

As the ’90s progressed, Clinton began to incarnate the equivocal. “A clear pattern has emerged—of delay, of obfuscation, of lawyering the truth,” Joe Klein wrote in a 1994 essay in Newsweek . “With the Clintons, the story always is subject to further revision. The misstatements are always incremental. The ‘misunderstandings’ are always innocent—casual, irregular, promiscuous. Trust is squandered in dribs and drabs. Does this sort of behavior also infect the president’s public life, his formulation of public policy? Clearly, it does.”

Dee Dee Myers, Clinton’s former press secretary, is more charitable: “[It] was a tactic that Clinton used more effectively—and I don’t mean it in a good way—than anyone I’d ever worked for,” she says. “In politics, people lawyer the truth, and Clinton did. That’s a fair criticism. Clinton would say things that were technically true but that created a misimpression that kind of intentionally sent people in the wrong direction. Or, more often, I think he tried to leave himself wiggle room and change his mind and say he never said [that].”

In a similar vein, both Hillary Clinton and Trump, perhaps the two most distrusted opponents in a modern presidential contest, perpetuated the post-fact syndrome during their 2016 race for the White House. Clinton, from her tenures as first lady (Travelgate) up through her time as secretary of state (Emailgate), was considered by many to be an unconscionable obfuscator. Trump, for his part, elevated lying to a dark art. “On the PolitiFact website,” New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof would report, “53 percent of Trump’s [public statements were rated as demonstrably] ‘false’ or ‘pants on fire’—a number that would climb to “71 percent… ‘mostly false’” on the eve of the election. This endemic fabrication was tactically deceptive in a manner reminiscent of totalitarian leaders—a pattern made all the more ominous, as Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter has pointed out, since Trump would routinely crib his “talking points from the dark corners at the bottom of the Internet.”

Trump would prove to be the ideal candidate for the era of fake news, hate blogs, “agita”-prop, fear-and-ballast news networks, nonstop gossip and Twitter-feed screeds. And it is no exaggeration to state that his candidacy would not have been possible, or viable, had it not been for the rhetorical and stylistic precedents set by the ever-parsing Bill Clinton—and his mendacious detractors on the right.

Crude and Canny

Two and a half decades after the Clintons appeared on 60 Minutes , America elected a president, who once bragged over an open mic that his fame allowed him the latitude to grab women by their genitals—largely without consequence.

By then the rules of sex scandals in American politics had changed. The 1990s had ushered in personal branding, reality programming, 24/7 news, tabloid scandal coverage and online self-expression. Although crude and predatory, Trump was a media maestro. He seemed to understand that harnessing the twin forces of traditional media and social media was the new mode for asserting power, for manipulating public opinion (to acquire power), for humiliating or undermining others (who were displaying too much power) and for perpetually deflecting or diverting the influence of those in other power centers (to maintain power). Kim Kardashian knew it, the Islamic State group knew it, Russian President Vladimir Putin knew it. And Trump did too.

His victory augured a new and chilling reality in America. And there was an unmistakably ’90s tenor to it all. Trump’s journey to the White House would have been inconceivable without the coarseness of the Clinton years, a coarseness equally attributable to popular culture and the newfound web, the president’s scandals and the prurience of his critics.

As Nina Burleigh wrote in Newsweek after the votes were cast in 2016, “Amid Trump confirming the size of his manhood on national TV, the return of Bill Clinton’s sexual-assault accusers and a gnarly campaign-capsizing FBI announcement regarding Anthony Weiner’s sexting, election 2016 was a national referendum on women and power.”

And on men in power. And race and power. And the substitution in American politics of rage for reason, entertainment for information and bluster for truth.

David Friend is a Vanity Fair editor, journalist and Emmy-winning documentary producer. This excerpt has been adapted from his new book, The Naughty Nineties: The Triumph of the American Libido (Twelve Books, 2017).

Related Articles