Donald Trump’s Delay Game Is Now In The Supreme Court’s Hands

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The Supreme Court ordered former President Donald Trump to respond to special prosecutor Jack Smith’s request for an expedited hearing on Trump’s claim he has absolute immunity from prosecution for the charges he faces related to his effort to steal the 2020 election, setting themselves up as the key decision-makers on whether Trump will face a significant trial before the 2024 election.

The fast move by Smith to skip the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals and go straight for a ruling from the Supreme Court happened for one big reason: timing. The prosecution of Trump for his actions leading up to and surrounding the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection is set to go to trial on March 4, 2024. If it keeps to that schedule, it will be the only one of the three biggest prosecutions Trump faces that is likely to be resolved prior to the presidential election.

And if Trump wins the 2024 election, the Department of Justice’s long-standing position that the sitting president cannot be prosecuted would likely shield him from justice. Trump’s best bet to avoid a trial before he can win the presidency is now in the hands of a conservative Supreme Court that has been intermittently skeptical of his most grandiose positions, even though he appointed three of its members.

A federal district court already ruled on Dec. 1 against Trump’s claim he has absolute immunity from prosecution for any action taken while in office. Trump appealed the decision to the D.C. Circuit appeals court, but Smith has now asked the Supreme Court to step in and rule first.

Smith asked the Supreme Court for an expedited hearing on the former president's claims of absolute immunity from prosecution on Dec. 11, 2023.

Normally, appeals rooted in immunity claims can take a long time as they wind from the district court through an appeals court hearing and then up to the Supreme Court. But appeals like Smith’s have become increasingly common on serious issues where time is of the essence ― or, at least, where the Supreme Court justices decide time is of the essence.

The most readily comparable case where the court accepted a similar appeal leap-frogging an appeals court is the 1974 Watergate tapes case of U.S. v. Nixon. Claiming executive privilege, Richard Nixon refused to hand over audiotapes from the Oval Office after Watergate special prosecutor Leon Jaworski subpoenaed them. The court ruled the president can protect certain documents and conversations with executive privilege but said a “generalized assertion of privilege must yield to the demonstrated, specific need for evidence in a pending criminal trial.” The decision led to the release of the unedited tapes and, ultimately, Nixon’s resignation from office.

More recently, the Supreme Court has accepted similar appeals in cases involving COVID restrictions, President Joe Biden’s student loan forgiveness and Texas’ abortion bounty hunter law, among others.

It is clear then that the Supreme Court can turn around an important decision like this in a short period of time. The timeline of U.S. v. Nixon is instructive.

Nixon appealed the May 20, 1974 decision by district court Judge John Sirica ordering him to comply with the subpoena for the unedited Oval Office tapes to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals on May 24. On the same day, both Nixon and Jaworski asked the Supreme Court to step in and take the case in lieu of the appeals court. The Supreme Court took up the case on May 31, held arguments on July 8 and released its opinion on July 24. It took two months from the date of the first appeal to the court for a decision to come down.

Applying the same timeline to Trump’s case means a decision could theoretically be reached in mid-February, allowing the March 4 trial date to stand, while any delay could push the date further back. The question then is whether the current Supreme Court justices want to move as fast as the justices did in U.S. v. Nixon. It is really all up to their judgment.

Despite Trump appointing three of the six conservative justices, the court has not been inclined to back him on his most outlandish legal forays. That is save for Justice Clarence Thomas.

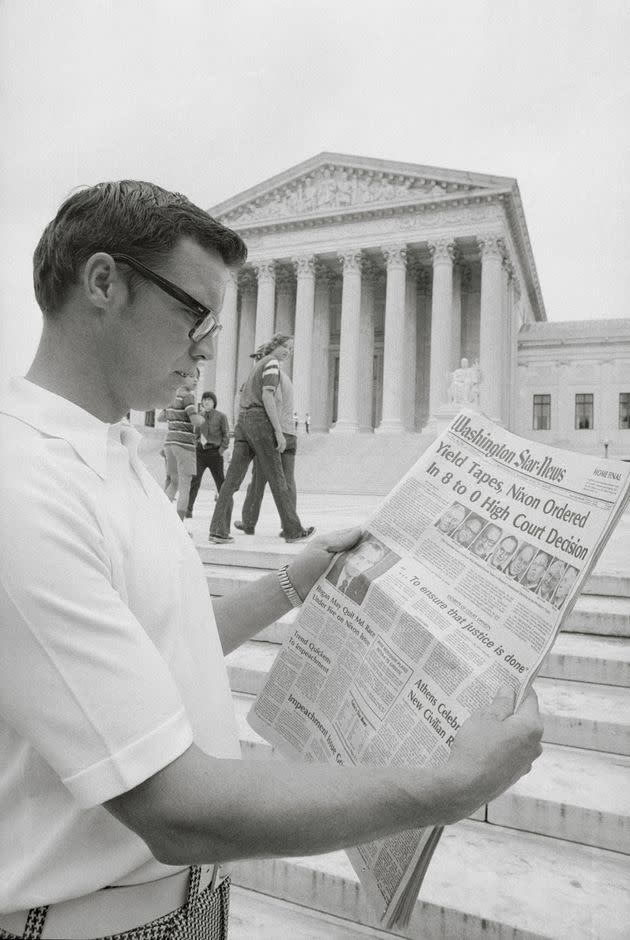

The Supreme Court took up the case of U.S. v. Nixon on an expedited hearing schedule in 1974. The court's decision forced Richard Nixon to hand over Oval Office audiotapes and led to his resignation.

When Trump tried to squash the House Jan. 6 Committee’s efforts to obtain official documents from his time in office, he filed suit to claim executive privilege. The court declined to take the case in January 2022, with seven justices joining an opinion by Chief Justice John Roberts. Only Thomas said he would grant review.

Later, the committee released messages from Thomas’ wife, Ginni Thomas, to Trump’s White House chief of staff, Mark Meadows, strategizing in support of the effort to steal the 2020 election. This revelation prompted outrage that Thomas had not recused himself from multiple cases revolving around Trump’s efforts to steal the election when his wife was, at least tangentially, involved in it.

Democrats like Senate Judiciary Committee chairman Dick Durbin (Ill.) and Sen. Richard Blumenthal (Conn.) have already called for Thomas to recuse from any case resulting from Smith’s appeal.

There is precedent in a somewhat similar situation. Prior to his appointment to the court by Nixon, Justice William Rehnquist served in Nixon’s Justice Department, working closely with many of the actors in the Watergate scandal, including Attorney General John Mitchell. Rehnquist recused from U.S. v. Nixon because of these relationships. The difference with Thomas’ situation is that the appeal in U.S. v. Nixon arose from Mitchell’s criminal trial, while Ginni Thomas is not a party to the case.

Ultimately, the decision will be up to Thomas. The same is true for the court’s timeline for hearing the case. It could be resolved in time for the March 4 date, or they could drag this out longer, pushing the trial into a potential conflict with Trump’s other trials. Or, if the court decides not to take Smith’s appeal, the process could extend beyond the election, allowing Trump to evade justice ― yet again.