Donald Trump picked a fight with the National Archives. It may be the end of him

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Many years from now, when the history books about the Trump era are written, they may yet note that his downfall came not at the hands of his political rivals, the Deep State, or even the voting public. The end, when it finally came, began when he picked a fight with an archivist.

The archivists of the National Archives and Records Administration (Nara) are no ordinary librarians, to be sure; they are the keepers of the presidential records – every memo, letter, gift and executive order that passes across a president’s desk. They painstakingly document and store all of those records on behalf of the general public, to whom those items belong.

But few of them could have imagined that they would be thrust into the spotlight in the way they have in recent weeks after their role in the series of events that led to an FBI search of Mar-a-Lago was revealed.

The National Archives in Washington DC, a looming neoclassical building flanked by 72 Corinthian columns, lies almost equidistant from the White House and the US Capitol. Its place between these two pillars of democracy is fitting; within its walls are housed some of the most important documents in American history: the original Declaration of Independence, the constitution and the Bill of Rights, to name a few. But it is also home to millions upon millions of government and historical records, which it is bound to preserve for the benefit of the public.

The mission of the National Archives goes far beyond record-keeping – as an institution, it views itself as a protector of democracy, and of history itself. An inscription carved into the side of the imposing building on Pennsylvania Avenue in giant letters gives a clue to the seriousness with which it takes this role. It reads: “This building holds in trust the records of our national life and symbolises our faith in the permanency of our national institutions.”

It seems apparent that Donald Trump, a man who spent much of his political life trampling over institutions and norms, underestimated the archivists and their mission. His alleged mishandling of government records now represents the greatest legal threat he faces and potentially the end of his political career.

The saga began during Mr Trump’s tumultuous exit from the White House in January 2021. Having battled against the reality of his loss for more than two months, and unleashed his supporters on lawmakers in the Capitol, Mr Trump was wholly unprepared for moving day.

On this day, traditionally, it is standard practice for the outgoing president to hand over all government documents in their possession to the National Archives. Mr Trump, as is his wont, did not follow tradition.

Photographs of his hasty departure from the White House showed staff carrying dozens of boxes to Mar-a-Lago, his residence in Palm Beach, Florida. Among those boxes, we now know, were dozens of classified and top secret documents that should have been handed over to the National Archives, which is responsible for assessing and storing those documents.

“It can be a fraught time, obviously, with administrations that were hoping to be re-elected. People are panicking,” Steve Greene, a former archivist for the Nixon Presidential Library for more than 15 years, told The Independent. “That’s totally aside from the situation they found themselves in in 2020, with an incumbent president that was rejecting the notion that they lost, which obviously created enormous challenges.”

“Even in the best of times, it’s kind of an all-hands-on-deck situation. It can draw in people from various offices in the National Archives who work almost continuously, very long hours and over the weekend to get this kind of work done. It’s important work and colleagues of mine that have done that repeatedly have my respect,” Mr Greene, who also worked at the National Archives in Maryland, added.

David Ferriero, the 10th archivist of the United States, would later recall the series of events that led them to suspect not everything had been handed over to the archives.

In an interview to mark his retirement in May, Mr Ferriero said he was told by the White House Office of Records Management that there were boxes in the White House residence that needed to go to the archives.

“As we were moving materials from the White House just before the inauguration, those boxes hadn’t shown up yet,” he told The Washington Post. “I can remember watching the Trumps leaving the White House and getting off in the helicopter that day, and someone carrying a white banker box, and saying to myself, ‘What the hell’s in that box?’” he added.

It took a few months for archives officials to realise that some important documents appeared to be missing from the boxes Mr Trump did hand over to them. Nara’s chief counsel, Gary Stern, wrote to Mr Trump’s lawyers to ask for their return in May.

“We know things are very chaotic, as they always are in the course of a one-term transition,” he wrote. “But it is absolutely necessary that we obtain and account for all presidential records.”

Mr Trump’s troubles might have ended here if he had quickly returned all the classified documents he had in his possession. But he went another way. Despite repeated requests from Nara officials Mr Trump’s team delayed and demured for months, before finally relenting and handing over 15 boxes to the National Archives in January 2022.

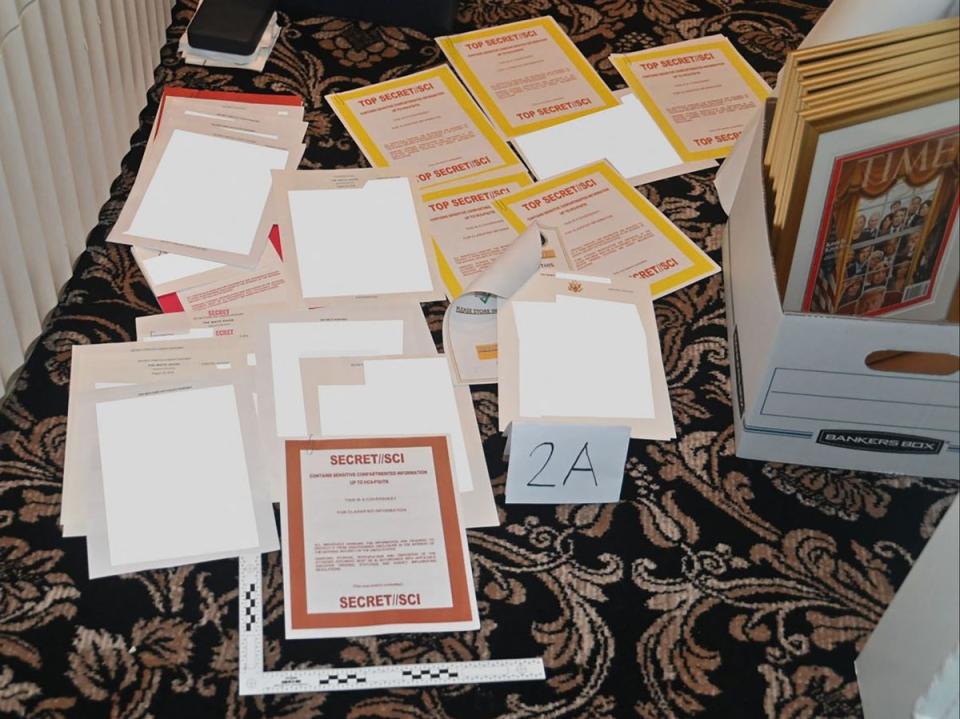

After going through those 15 boxes, the archivists made a shocking discovery. The boxes were filled with documents clearly marked as classified, secret and top secret – the highest security classifications – mixed in with printouts of news articles and other items. In total, they found 184 unique documents bearing classification markings, 67 documents marked as confidential, 92 documents marked as secret and 25 documents marked as top secret. It was then the National Archives took the extraordinary decision to refer the matter to the Department of Justice (DoJ) for a possible investigation into the mishandling of classified records. Agency officials were keen to recover any more documents in the former president’s possession.

“Based on everything I’ve been told about the way that administration conducted business, I was shocked, but not surprised,” said Mr Greene. “It’s concerning, obviously,” he added. “The National Archives normally maintains a pretty low profile and I used to kid people that we liked it that way.”

Mr Greene said the national security component of those documents was “certainly the foremost issue” in prompting urgency from the National Archives.

“If it was solely a records management dispute, I doubt it would be generating the level of interest and partisan bickering we’re seeing,” he said, adding that concern over the Trump administration’s handling of documents was “longstanding.”

“The rumours of him tearing up documents, and later of actually disposing of documents in the toilet, have been circulating for some time. And it’s not a good look for anyone,” he said.

But he added that part of the problem lies in the imbalance between this relatively small agency and the power of the White House.

“We’re a tiny federal agency with outsized responsibilities, but without any realistic ways to enforce them,” he said.

Without the means to force Mr Trump to hand over the documents, the archives took the matter to the DoJ. That referral led to a DoJ investigation, which eventually led to a search of Mr Trump’s Mar-a-Lago property, where yet another trove of classified and secret documents was found. An inventory of the search that was unsealed on Friday revealed that agents seized more than 100 “unique documents with classification markings”, including three stored in Mr Trump’s desk, as well as 90 empty folders that had once held extremely sensitive documents.

Following the Mar-a-Lago search, Mr Trump and his allies sharply criticised the archives, drawing it into a political battle it was ill-equipped to handle.

“They could have had it anytime they wanted – and that includes LONG ago. ALL THEY HAD TO DO IS ASK. The bigger problem is, what are they going to do with the 33 million pages of documents, many of which are classified, that President Obama took to Chicago?” Mr Trump wrote on his Truth Social website on 12 August.

That post prompted a rare response from the National Archives, which quickly rejected Mr Trump’s baseless claim. It said in a statement that Nara “assumed exclusive legal and physical custody of Obama presidential records when President Barack Obama left office in 2017, in accordance with the Presidential Records Act.”

“As required by the PRA, former president Obama has no control over where and how Nara stores the presidential records of his administration,” the statement added.

Although the most controversial elements of the case passed from the hands of the National Archives to the DoJ and the FBI, the attention on it did not.

In a letter to Nara staff this week, acting archivist Debra Wall said that the agency had been under attack for its role in the investigation into Mr Trump’s handling of records.

"The National Archives has been the focus of intense scrutiny for months, this week especially, with many people ascribing political motivation to our actions. Nara has received messages from the public accusing us of corruption and conspiring against the former president, or congratulating Nara for ‘bringing him down’,” she wrote, according to a copy of the letter obtained by CNN.

“Neither is accurate or welcome,” she added. “For the past 30-plus years as a Nara career civil servant, I have been proud to work for a uniquely and fiercely non-political government agency, known for its integrity and its position as an ‘honest broker.’ This notion is in our establishing laws and in our very culture. I hold it dear, and I know you do, too.”

“We will continue to do our work, without favour or fear, in the service of our democracy,” Ms Wall concluded.

The National Archives said it does not comment on matters of security when asked by The Independent about reports that its staff had faced threats.

On a scorching summer day this week, tourists and visitors flowed in and out of the National Archives museum as usual. They gathered in the grand rotunda in the heart of the building and stood in front of America’s founding documents. Out front, two young women wearing Maga hats took selfies with the grand columns as a backdrop. When asked by The Independent if they were angry at the archives for their role in Mr Trump’s troubles, they replied that they were entirely unaware of the furore.

As Mr Trump’s legal peril mounts, Mr Greene is hoping the archives can get on with the important job of preserving history.

“It’s sad for all of us in so many ways. But I think I have to give some credit to my colleagues, they handled a horrible situation very well,” he said.

“The people that work in the National Archives are professionals, they’re not partisans. Their sole interest is that the raw material of history is preserved and the laws and regulations related to national security information are observed.”