'I don't understand anything': Thanks to pandemic schooling, college students fail math

Andrea Hernandez studied the multiplication table nearly every day during the summer between her third and fourth grade years. Sitting at her family’s kitchen table in Dallas, she printed the arithmetic over and over in a yellow, spiral-bound notebook.

When she started at a new school that fall, she breezed through the timed math tests. From then until the coronavirus hit, when she was a 16-year-old precalculus student, Hernandez shined in the classroom.

Then, like millions of other students across the country, Hernandez was forced to shift to learning online. For the rest of her junior year and most of her senior year, she learned from a laptop in her family’s living room, with her younger sibling taking Zoom classes down the hall in their shared bedroom.

She felt she lost her muscle for being a student. The standards for online learning during her junior year weren’t just lower than they had been in the classroom, she said: “The standards weren’t even there at all.”

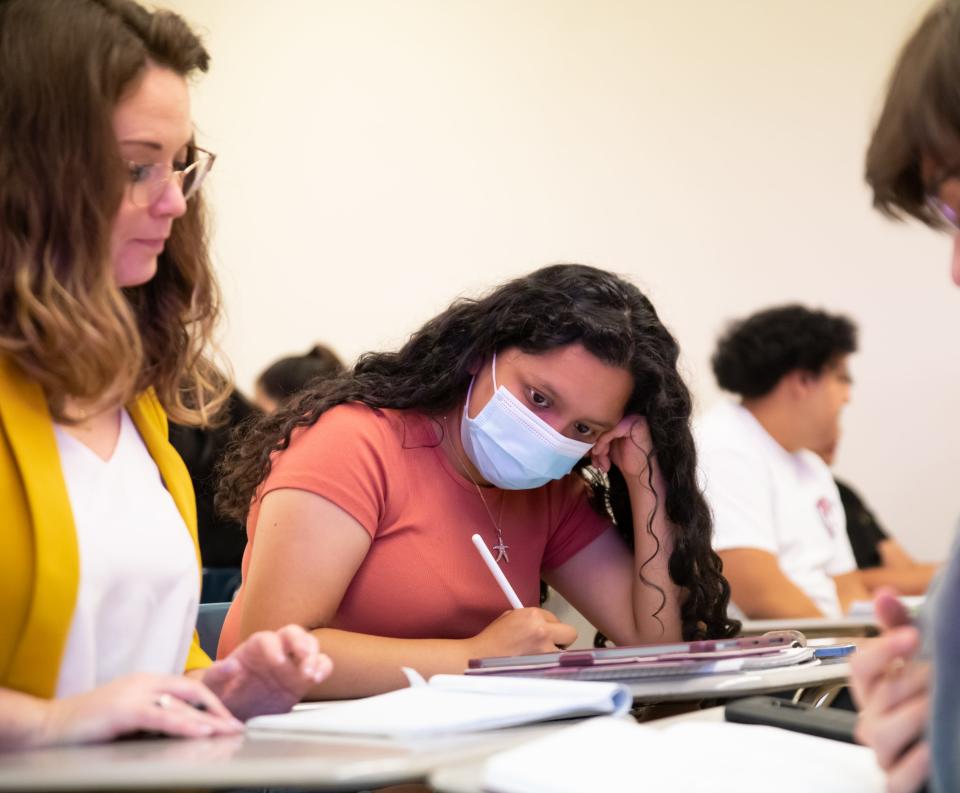

By a slim margin, Hernandez, a math major, failed the math placement exam that would have landed her a seat in calculus in the fall as a first-year student at the University of Texas at Austin. She retook precalculus and earned an A. Now, she spends four days a week in an unusually small seminar-style calculus class with 31 other aspiring mathematicians and engineers.

“I want to say it’s going good so far. But, you know, there’s just some things where I look at them and I’m just like: ‘Where’s the math? I just see letters.’ I don’t understand anything,” Hernandez said. “I’ll just sit there, kind of lost.”

More than 20 of her classmates in the calculus seminar took the larger, lecture-style class last fall – and failed.

Many students whose last years of high school were disrupted by the pandemic are struggling in the foundational college courses they need to succeed later in their academic and professional careers. Professors and students say the remote learning that students were stuck with during the pandemic wasn’t as good as what they would have had in person. The students were also often distracted – trying to learn while grappling with health, financial and family stressors.

Now, after two years of cobbled-together pandemic learning, many college students not only are less prepared than they should be, but they’ve even forgotten how to be students.

And more underprepared high school graduates are likely to be coming right behind them, putting unprecedented pressure on faculty, counselors and advisers.

Low-income and students of color hit hardest

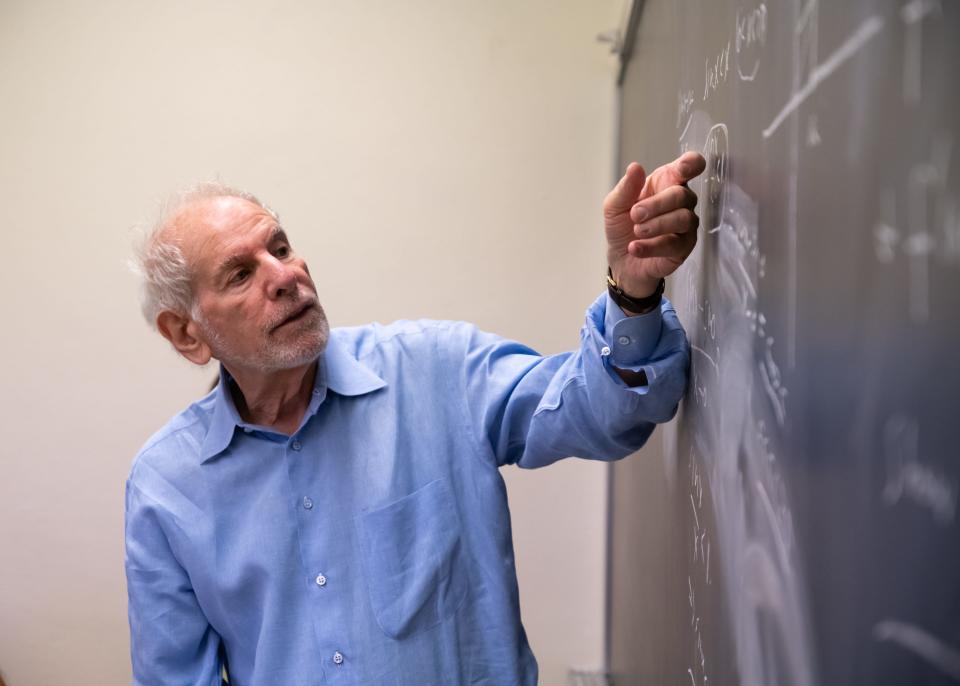

Hernandez’s math professor, Uri Treisman, is nationally known for his techniques and philosophies for teaching calculus. For his classes, he specially selects at-risk students like Hernandez who might benefit from his approach. He said the fall 2021 semester of first-year calculus was the most difficult he has had in his 50-year career.

His students were making basic errors in algebra and trigonometry from the beginning. Despite Treisman doing all he could to help, about 25% of his students failed in the fall – compared with 5% in an ordinary year.

Instead of emails from students asking for letters of recommendation, Treisman’s inbox was flooded with emails from students anxious to retake his class, apologizing for a poor performance and for being unprepared.

“It was really hard for us emotionally, because we know the stakes for our students,” Treisman said of himself and his co-professor, Erica Winterer. “Their failure is my failure.”

From the tiniest kindergarteners to college-ready high school seniors, nearly all students had their education disrupted starting in March 2020. As a result, the full scope of the college unpreparedness problem is not yet known.

Even so, educators and experts worry that students from historically underserved backgrounds could be disadvantaged even further by the disruptions. Economic fallout from the pandemic hit low-income Americans, people of color and people without college degrees the hardest, so students from families in these groups are more likely to come to college having faced greater challenges over the past two years than their peers.

‘I want it for me’: 1st-generation college student beats COVID-19 barriers to stay in school

“Here and everywhere around the world, the wealthy are concerned and nervous about the futures of the children, and they're investing heavily in ensuring their children have an advantage,” Treisman said. “So, that nervousness requires that those who care about equity work much harder.”

Even in a normal year, Treisman said, students don’t all show up with the same level of preparedness or knowledge base. But because of the pandemic, his students are contending with different stressors than they otherwise would be.

Hernandez, for example, was taking her 12th grade math class via Zoom in her family’s living room when her father returned from work hours early, visibly upset. She followed him into his bedroom, where he told her that her grandfather, who lived in San Luis Potosí, Mexico, had died of COVID-19.

She had leaped from her makeshift desk so quickly she hadn’t turned off her camera or taken off her wireless headphones. When she learned of her abuelito’s death, the math lesson was still playing in her ears.

For students like Hernandez, it was hard to focus on education when their loved ones were facing life-threatening illness, financial strife, child care uncertainty or general instability because of the pandemic. Often, school days became about just about getting by rather than excelling.

Students passed classes without knowing material

In a typical year, 2% to 4% of Kristin Patterson’s genetics students at UT Austin are unable to pass her course. Last fall, about 20% of students failed. She said she noticed right away that they were struggling, and her worries were confirmed three weeks into the semester, when she scored the first exam. The rest of her students, she said, were just as prepared and engaged as they have been in years past.

Patterson, an associate professor of instruction, said the college does not yet fully understand how the pandemic has affected student preparedness, but some trends are emerging.

Because of how quickly the pandemic hit, most educators across the country were caught off guard, trying to convert their in-person curriculum overnight into something that would work online.

And many educators, in high school and college alike, had trouble accurately assessing their students’ progress.

Patterson suspects it’s more difficult to assess students’ understanding of the class material with remote tests and quizzes, for which students can consult more resources. Without reliable indicators of progress, she said, she’s worried professors “are just assuming mastery when it may not exist.”

During the 2020-21 academic year, UT adopted a policy allowing students to designate up to three of their courses to be graded as pass/fail rather than with letter grades, Patterson said. The emergency policy allowed students to “pass” these classes with a grade as low as a D-minus, so students who earned a D in a prerequisite course could move on without necessarily having mastered the material.

“It seemed like there needed to be a policy and expectation change in the face of an emergency,” Patterson said.

The upshot: "Students who would not normally have passed (were) getting a passing grade and moving on to the next course."

Patterson noticed her students also struggled to adjust to life on campus.

Some students didn’t understand the difference between her class’s main meeting period and a small-group discussion regularly scheduled for another time and place, probably because their first year at UT was so abnormal. After nearly two years of an altered learning environment, they have to relearn how to interact in a physical classroom, how to socialize and how to manage the expectations of being a college student at the same time.

The new pandemic phase: Colleges test the limits of ‘normal’ school years

The nature of what is “baseline” or “normal” for an incoming college student has changed, said Ed Venit, a manager at the education research firm EAB and an expert in student retention and success. Colleges will have to adjust.

At the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, the rates of students receiving D or F grades or withdrawing from a course are up, and math placement-test scores are down. So administrators added sections of a general college preparedness course to help students develop time management and study skills.

The university is known for its Meyerhoff Scholars Program, designed to prepare students from underrepresented backgrounds for STEM careers. Brad Peercy, a professor and undergraduate program director in the department of math and statistics, said he worries that the pandemic could push more students of color and low-income students from those fields. “That’s definitely the risk,” he said.

Representation in STEM: SpaceX launches rockets from one of America's poorest areas. Will Elon Musk bring prosperity?

At Kansas State University, where first-year students are showing both content and process gaps, they’re being monitored with an early alert system that uses low grades and missed assignments to identify students who are having a hard time and then connect them with extra resources.

'I don't mention they failed. I don't lower the standard'

Treisman, having seen his students struggle in the fall, is scrambling to figure out how to help them recover.

“It’s so tempting to lower the standard,” Treisman said. “The big risk, from a teaching perspective, is that I give them a good grade and they’re not prepared for what comes next.”

Not only is he preparing them to take their next calculus course, but he also must backfill the prerequisites they’ve come to college without, he said.

After Treisman administered the first exam last fall, Winterer, his co-professor, emailed all the students who failed, asking them to meet with her. She tried to help them develop a plan to get back on track, offering them structured study groups – an intervention that has worked for Treisman and Winterer’s students in the past.

This semester, even though they are teaching a section made up almost entirely of students who failed the course in the fall, Treisman said they never remind them of that.

“I don’t mention they failed. I don’t lower the standard,” he said. “I have to remind them, maybe put a little more energy into reminding them, that they’re really going to be leaders. That they will figure out how to do this.”

For the first 15 minutes of the sections Treisman teaches, he doesn’t mention the equations or formulas the students need to master. Instead, he introduces them to mathematicians and scientists, past and present, and talks them through possible career paths. It’s a strategy to help them build back their academic identity, he said.

Students who fail courses face other obstacles as well. If their GPAs drop, they risk losing their financial aid, which could make continuing toward a degree impossible. If they move on without being ready academically, Treisman worries that they will feel as if they don’t have control over their academics or their lives. They may choose a career path for the wrong reasons.

“It’s control over their lives and their futures that is at stake,” he said.

If his students can’t be successful, Treisman worries that their high schools and communities will be less inclined to send future students to colleges like UT, denying them opportunities that could change their lives.

And Venit, the education researcher, worries that the students who were in financially stable families before the pandemic will be able to bounce back, and those who weren’t – overwhelmingly students of color, first-generation students, rural students – will have a much more difficult time.

“If those folks don’t have the opportunity to advance themselves economically, then this is a rich gets richer situation, and poor stays poor situation,” Venit said. “That reverses the trend that we’ve been trying to do for 20 years in higher education.”

For Hernandez, who is nearly halfway through her second semester at UT Austin, the goal is clear: Pass calculus, finish college and become a middle school math teacher.

To do that, she has to rediscover the girl who, nearly 10 years ago, was always the first to turn in her timed multiplication tests.

Contributing: Caroline Preston, The Hechinger Report

This story about unprepared students was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: College students get failing grades in math, science, thanks to COVID