Doolittle Raiders relied 'on the kindness of Chinese strangers.' This Gulf Breeze man helped

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

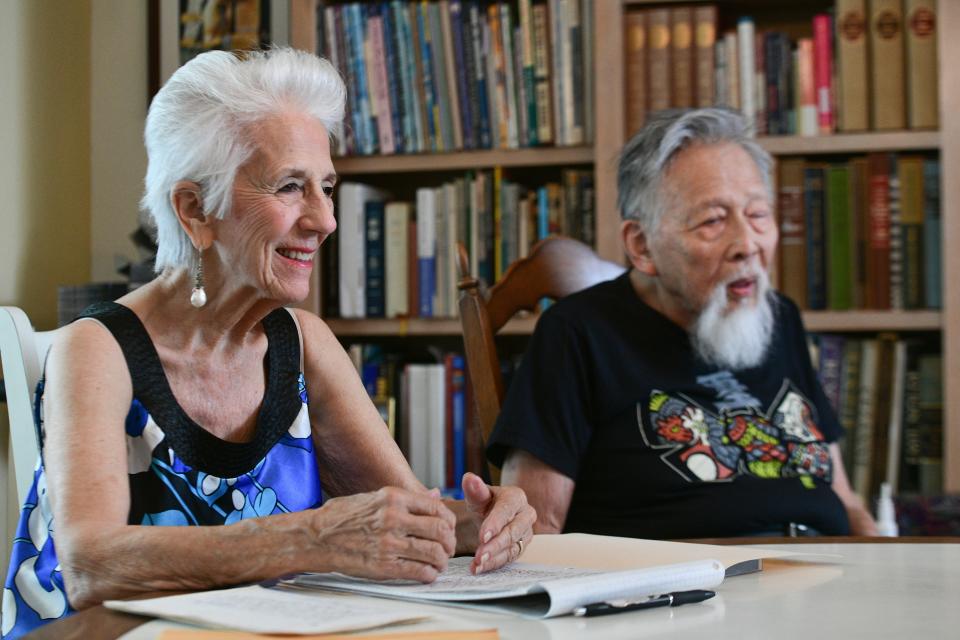

GULF BREEZE — An art-filled home on a quiet residential street nestled between the East Bay and Santa Rosa Sound hardly seems like a place where wartime atrocities would be a topic of conversation.

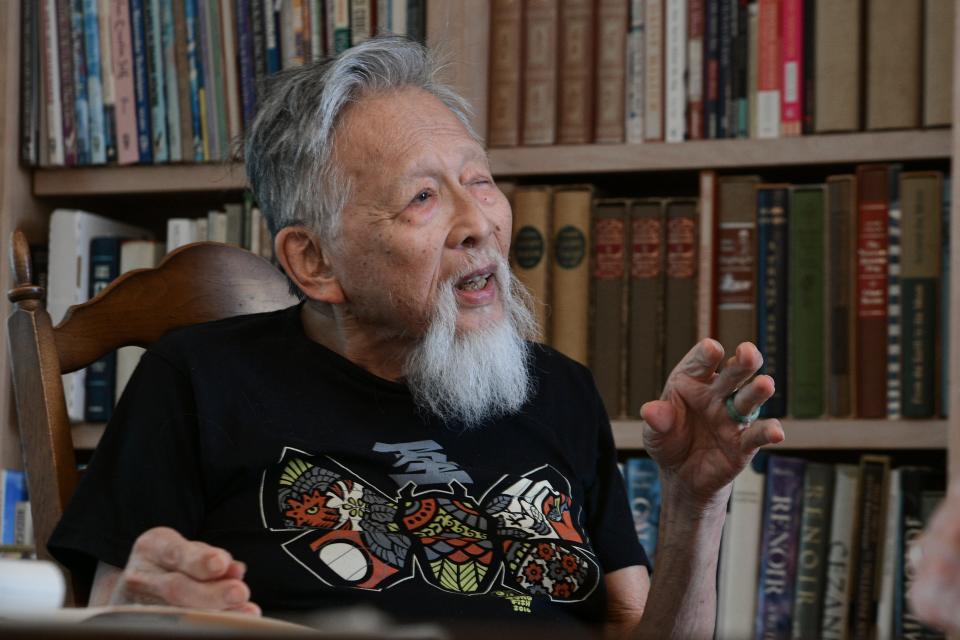

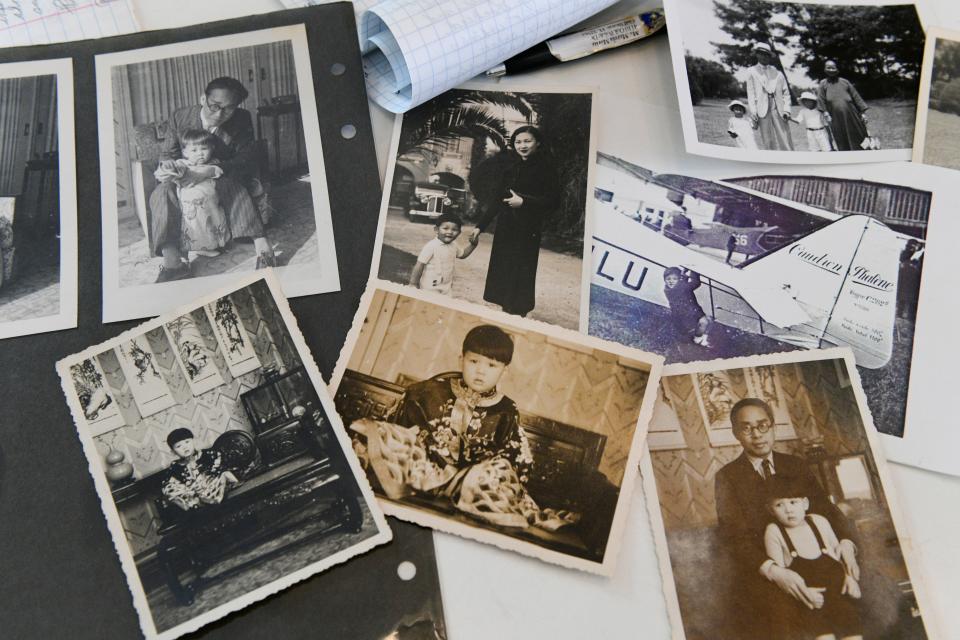

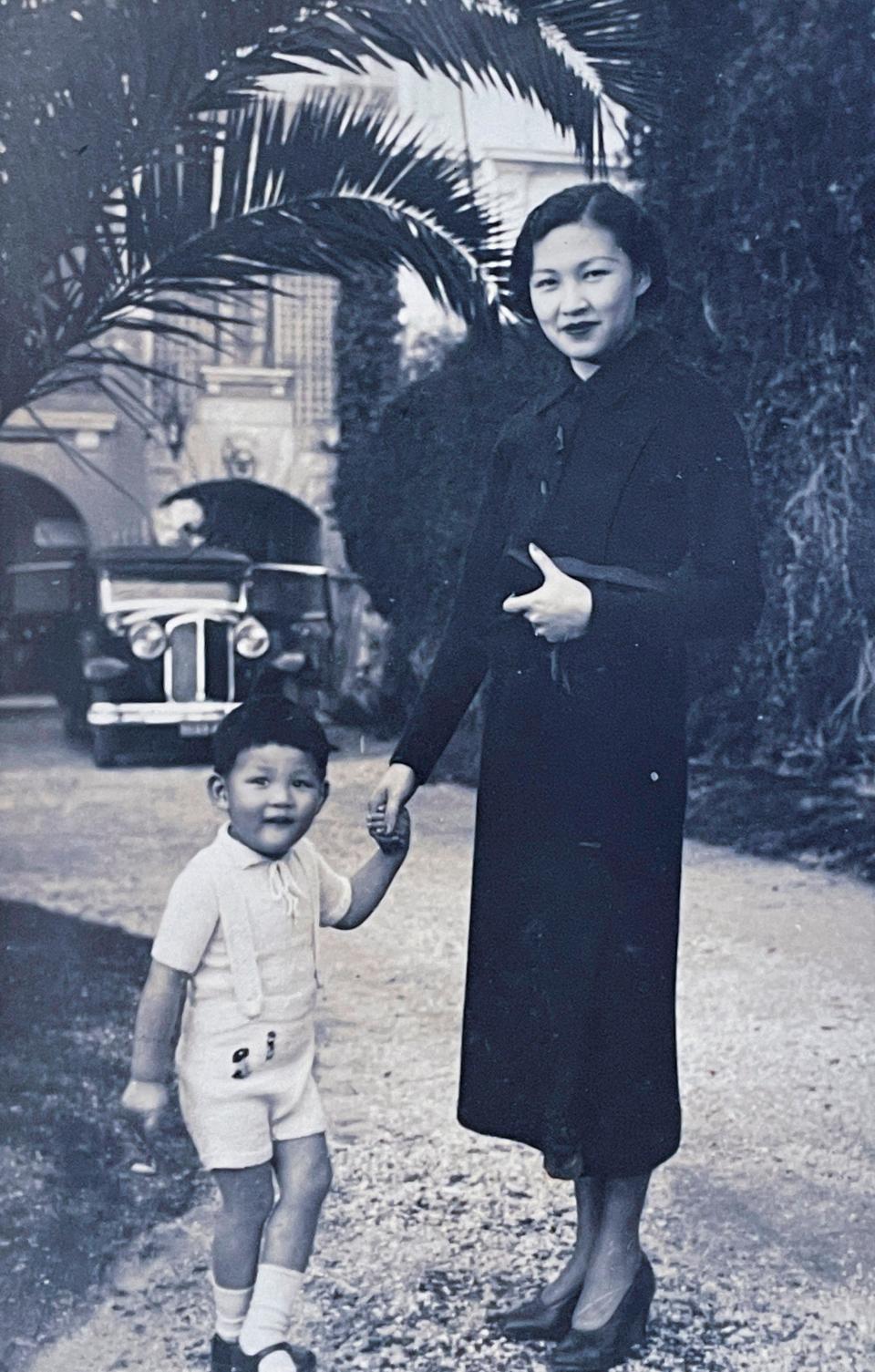

Yet that's just what happened on a recent afternoon as 90-year-old Pax Cheng recounted his experiences growing up in China during the Sino-Japanese War, which would later merge into a theater of World War II as horrific Japanese incursions into China continued.

As part of those years spanning the late 1930s and early 1940s, Cheng, as an 11-year-old boy studying at a boarding school in Shanghai, played a supporting role in the story of the Doolittle Raiders — at risk of serious Japanese reprisal.

The World War II exploit by 80 volunteer airmen from the U.S. Army Air Forces is well-remembered and honored across Northwest Florida, inasmuch as the Raiders, under the leadership of Lt. Col. James Doolittle, spent three weeks training for their mission at what was then Eglin Field, part of modern-day Eglin Air Force Base.

The Doolittle Raiders, loaded in five-man crews aboard 16 B-25 bombers, launched from the aircraft carrier USS Hornet in the Pacific Ocean on April 18, 1942 — the first time that bombers had taken off from an aircraft carrier — and hit military and industrial targets in Japan.

More on the Raiders' legacy: Doolittle Raid brought hope after Pearl Harbor; 80 years later, mission still 'unbelievable feat'

The damage caused by the raid was relatively slight, but it proved that Japan was not beyond the reach of American air power, and provided a morale boost to U.S. military personnel and the American people just four months after Japan's devastating sneak air attack on Pearl Harbor.

But because the Doolittle Raiders had to leave the USS Hornet early after the carrier was spotted by a Japanese patrol boat, they wouldn't have enough fuel to make it to friendly airfields in China as planned.

'Ready for the Doolittle rescue'

And that's where 11-year-old Pax Cheng's part in the story begins. Cheng was part of a politically connected family, and despite his youth, Chinese adults working to thwart Japanese intentions in China knew he could be trusted, Marcia Moritz, a longtime companion of Cheng, said during a recent interview.

Knowing that the Doolittle Raiders would need assistance as they bailed out of their fuel-starved planes over China or tried to land them, the Chinese began a surreptitious effort to ensure there would be people nearby to help the downed airmen as they worked to make it to their ultimate destination of Chongqing, then the seat of the Chinese Nationalist government.

"A guy in a blue coat — I didn't know who he was — came to the school and whispered to me a message, and I was to pass on this message to a woman (who would identify herself to me) as 'Ouija Board'," Cheng recalled.

More: 'The true home': Northwest Florida State College gets piece of historic Doolittle Raider bomber

All these years later, Cheng can't recall what the coded message was, except to remember that it was just part of a message that would ultimately make its way, in full, to the people charged with ensuring the Doolittle Raiders would get a friendly and helpful welcome.

"It was a very brief message," he said. "I didn't understand what it was. It was kind of 'don't ask, don't tell, pass the information on'."

"Everything was done in secret codes because we didn't want the Japanese to catch on," Cheng explained.

A short time later, Cheng found himself living out the intent of the message as he waited with other people — lying in concealment in the grass on the outskirts of Shanghai — for what he would later learn was the anticipated arrival of the Doolittle Raiders.

"Hundreds of people" stretched from the outskirts of Shanghai to the Russian border more than 1,000 miles away, "were ready for the Doolittle rescue," he said

Helping the Raiders in China

Cheng himself had no direct contact with the Raiders as they bailed out of their planes, ditched them along the shore or crash-landed across a wide expanse of the Chinese countryside.

"They just flew right past me," he said. "I was hiding in the grass."

Cheng remembers being in the shadow of a B-25 passing above as he waited, and even 80 years removed from that day his admiration for the Raiders remains as strong as it was that day.

"... (A)ll those flyers, they knew they had to take a chance," he said. "They knew they wouldn't be able to go back to the ship, but they went ahead anyway."

Related: One last toast: Legacy of Doolittle Raiders honored at 'extraordinary' Final Goblet event

After his own experience waiting to help the crews, Cheng would hear tales of how others among his countrymen did help the American flyers. Some of the Doolittle Raiders, he said, were hidden in a cemetery.

"The Japanese were extremely superstitious," he said. "They would not go into the cemetery."

Cheng's story is part of what had, until fairly recently, been a little-known footnote to the story of the Doolittle Raiders, which has been focused on the American airmen and the effect of their mission on the American war effort.

As noted on a website maintained by the descendants of the Doolittle Raiders, at https://bit.ly/3wyvF0P, the aircrews, once down in China, "... had to rely on the kindness of Chinese strangers, who provided many of them with shelter and food, tended their injuries and led survivors on perilous journeys to evade Japanese patrols. The website goes on to note that "... more and more Chinese have come forward to commemorate the Doolittle Raiders’ mission in recent years."

'The Little Devils'

Cheng's resistance to the Japanese went far beyond his willingness to assist the Raiders.

"A group of us, the Japanese called us the 'Little Devils'," Cheng said. Among the things he said they did was to use fluorescent paint to mark the roofs of buildings being used by the Japanese so that they could be attacked at night by friendly forces.

As a child in wartime China, Cheng saw a number of horrific incidents. In particular, he remembers seeing a Chinese man dismembered and killed by Japanese bombing.

"He crawled on the street, dragging his intestines," Cheng said. "His leg was on one side of the street, and his body was on the other side."

He also remembers what happened to a family near his school that continued to play mah-jongg, a Chinese origin tile-based game similar to the Western card game called rummy, after the Japanese had banned the game. The Japanese, Cheng recalled, "dragged them out and chopped their heads off with samurai swords" and then dumped the mah-jongg tiles on top of their bodies.

Understandably, Cheng had to give some thought to his own safety. In his boarding school, he took time to arrange stacks of boxes into something of a labyrinth, in which he could conceal himself from Chinese troops.

"They dragged my classmates out one by one, and they never came back," Cheng recalled of his school days.

Eventually, Cheng's father was offered a diplomatic post in Cuba, and he took Cheng and his sister with him. From there, Cheng would be sent to the United States for high school, where he first met Moritz, and then on to college, where his experiences included providing sound elements for then-student filmmaker Orson Welles.

Cheng's colorful life included design work with aeronautical and defense contractor Lockheed, becoming a master at wallpaper hanging (it paid more than Lockheed, he explained), and in later years working as a rancher.

But even with decades now separating him from his childhood in wartime China, Cheng suspects that he still carries wounds, albeit invisible ones, from that time.

"Being our age," he said, looking at Moritz, "many, many friends are passing, and I found out that when I go to a funeral, I can't shed a tear. I got immune to it. I feel sad, I feel bad for the survivors, but ... ."

This article originally appeared on Northwest Florida Daily News: Chinese resident of Gulf Breeze played role in Doolittle Raid