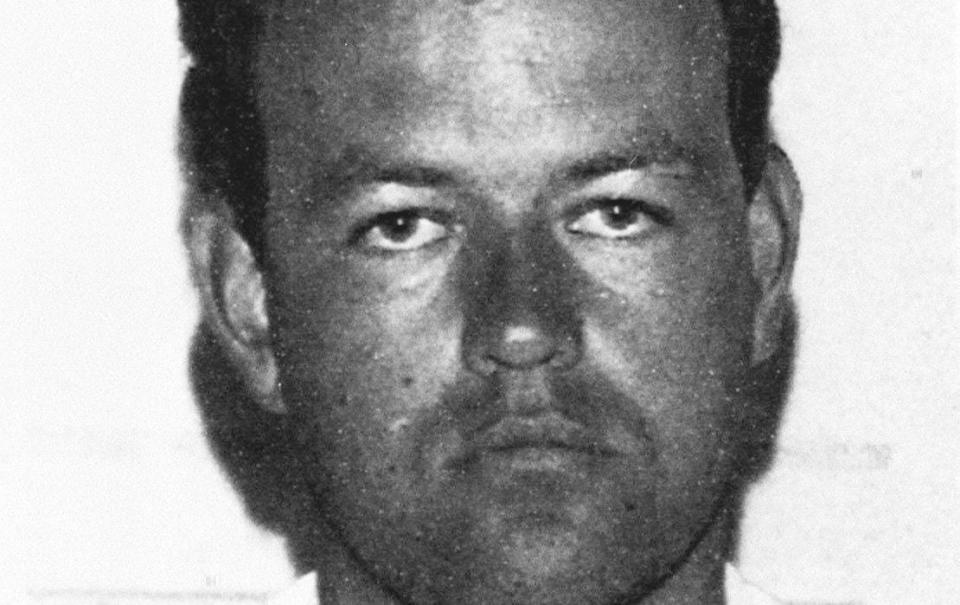

Double child murderer Pitchfork case proves Parole Board needs reform, says former justice secretary

The Parole Board should be renamed with a focus on protecting the public after Colin Pitchfork, the double child murderer, was recalled to prison for “concerning” behaviour, said the former justice secretary.

Robert Buckland, who opposed Pitchfork’s release when he was in the post, said its name should be changed to “public protection board”, alongside tougher rules for assessing the risk of freeing criminals into the community.

In an online article for The Telegraph, he said the name change would “convey a much clearer idea as to the board’s proper role and function”.

Mr Buckland, who set up a root-and-branch review of the Parole Board when he was at the Ministry of Justice, said the test for releasing criminals should also be amended, so the board gives greater consideration to the risks posed by the offender to the public.

Pitchfork, 61, was jailed for life for raping and murdering Lynda Mann, 15, in 1983 and Dawn Ashworth, also 15, in 1986 in Leicestershire. He was ordered to serve a minimum of 30 years but was released in September, despite Mr Buckland taking legal action to try to keep him behind bars.

Pitchfork case shows 'my concerns were justified'

Mr Buckland said the current test is whether the board is satisfied that it is “no longer necessary for the protection of the public” to keep a convicted criminal in jail. Yet this could mean the offender could still be released, even if it was “safer” to keep them behind bars.

“The test means that nothing short of necessity will do. In other words, whilst it might on balance be safer for the offender to stay inside, that won’t be enough to prevent their release,” he said.

“I would urge ministers to come up with an alternative that in essence allows the board to focus in each case as to how protection of the public can best be maintained.

“There will still be many cases where release on licence does allow this, but our aim should be to avoid the revolving door of release and then recall, as in Pitchfork’s case, with resultant damage to the system’s reputation.”

Pitchfork had been subject to the strictest licensing conditions imposed on an offender in modern UK history. He is understood to have breached one of nearly 40 rules, but the Ministry of Justice said he had not reoffended or compromised public protection.

“To see him returned to custody as a result of good work by experienced probation officers applying some of the toughest licence conditions ever seen in this country gives me cause to say that my concerns were justified,” said Mr Buckland.

Now, he said, there needs to be greater transparency in the decision making by the board including opening up its deliberations to the public to hold it to account.

“The presumption that Parole Board hearings should always be held in private should be abolished. With remote technology, access for those with a direct interest, the public and the media can be achieved,” said Mr Buckland.

At the same time, he recommended that the Board should be required to publish “fuller reasons” for their decisions, allowing for sensitive personal information not to be included.

“If we are to increase public understanding of and confidence in the system, openness should be the norm. We owe these changes not only to the families of Pitchfork’s victims who have been through unimaginable hell, but to the wider public too,” said Mr Buckland.

Parole Board changes needed to 'avoid the revolving door of release and then recall'

By Robert Buckland, former justice secretary

When it comes to the case of notorious double child murderer Colin Pitchfork, his release from prison a few months ago and his very swift recall to custody only a few weeks later, I do not think that I can be criticised for saying “I told you so”.

Having earlier this year requested for the Parole Board to reconsider its decision to release Pitchfork on the basis of evidence of real doubts about his sincerity in cooperating with the authorities, to see him returned to custody as a result of good work by experienced probation officers applying some of the toughest licence conditions ever seen in this country gives me cause to say that my concerns were justified.

Whilst it is reassuring that, if he was being sentenced nowadays, the court would have most likely imposed a whole-life order upon him, meaning no release on parole, the fundamental question as to why Pitchfork was released in the first place does not go away.

In our election manifesto, we made a commitment to setting up a root and branch review into the work of the Parole Board, the independent body that is responsible for all decisions to release prisoners from custody or to move them to more open conditions within the prison estate.

Although we had already carried out some reforms to the system, such as a new power for the Justice Secretary to ask the Board to reconsider cases, more needs to be done in order to increase public confidence in the system.

Like it or not, cases like Pitchfork’s have far-reaching effects on how the entire system is viewed. Making assurances that all is well and that nothing needs to change will not be good enough.

I set up the review late last year and its work has been continuing. I hope that it will soon be completed and published very soon, which was my firm intention. In advance of its findings, what in my view are the key elements of a meaningful change?

Here are five suggestions.

Firstly, I am not convinced that the role of the Parole Board is properly understood. It is often assumed that decisions whether or not to release prisoners are made on the basis of their conduct whilst in prison. The old and misleading adage “time off for good behaviour” comes to mind.

Whilst their conduct in prison, the original offences for which they were imprisoned and their previous criminal records are all relevant issues in looking at a prisoner’s progress, the Parole Board decision is in reality about future risk.

The test for release is whether the board is satisfied that it is no longer necessary for the protection of the public that the prisoner be kept in jail. Is this the right test, however? The test means that nothing short of necessity will do. In other words, whilst it might on balance be safer for the offender to stay inside, that won’t be enough to prevent their release.

I would urge ministers to come up with an alternative that in essence allows the board to focus in each case as to how protection of the public can best be maintained. There will still be many cases where release on licence does allow this, but our aim should be to avoid the revolving door of release and then recall, as in Pitchfork’s case, with resultant damage to the system’s reputation.

Secondly, as a key part of the drive to increase public knowledge, the Parole Board should be renamed. My suggestion is the Public Protection Board. This would convey a much clearer idea as to the Board’s proper role and function.

Thirdly, there is a clear conflict between the power of the Justice Secretary to ask for the Parole Board to reconsider a decision to release, and their direct role in presenting an application to the Board for release in the first place.

The Secretary of State should play no part in the initial proceedings. The Prison Service should prepare a file of material, but the Justice Secretary should only be involved if necessary after decisions are made by the Board, making an application in appropriate cases for reconsideration if they decide that a decision was unreasonable or that it was not made on all the information that should have been available.

Fourthly, the presumption that Parole Board hearings should always be held in private should be abolished. With remote technology, access for those with a direct interest, the public and the media can be achieved. We should also recognise that many victims do not wish for a public hearing in the case that involves them, so that decision should be one for the Board.

Finally, whilst it is welcome that summaries of the Board’s decisions are now prepared, the publication of fuller reasons for their decisions, with allowances for sensitive information not to be included, should become the norm. If we are to increase public understanding of and confidence in the system, openness should be the norm.

We owe these changes not only to the families of Pitchfork’s victims who have been through unimaginable hell, but to the wider public too.