How downtown Boise, ‘one of the finest’ in U.S., was nearly bulldozed for a shopping mall

For roughly two decades, developers and urban planners considered bulldozing many of downtown Boise’s historic buildings to make way for a shopping mall.

A handful of Boise icons, such as Chinatown, were lost in the push to revitalize the area amid a lull in downtown business patronage in the 1960s and 1970s. But the ultimate failure of the plans preserved the historic integrity of downtown, which has allowed it to flourish as an attractive destination among locals and tourists today.

“Our downtown is one of the finest downtowns in the country, and it’s because it kept much of its historic integrity,” said Clay Carley, a prominent Boise developer and former president of the Downtown Boise Association. “A mall would have forever changed that. Right now, people would be saying, ‘How do we undo this?’”

Mall craze comes to Boise

From 1965 to the mid-1980s, the Boise Redevelopment Agency — later rebranded as the Capital City Development Corp. — planned to level most of the buildings within eight city blocks downtown.

The area, bounded by Bannock and Front streets and Ninth Street and Capitol Boulevard, would become a regional shopping mall. In the late 1970s, the Winmar Co., a Seattle-based development firm, proposed the most feasible plans to date: a 780,000-square-foot indoor shopping center anchored by three department stores.

Winmar Co. was the fifth developer tapped for the mall project, and by then confidence in the idea was deteriorating. One city council candidate, running in opposition to the plans, called the mall concept a “loser,” the Idaho Statesman reported at the time.

But the urban renewal agency pushed forward, fueling what a Statesman columnist later called a “bitter, ugly battle.” The mall was meant to revitalize shopping and property values that had withered downtown, and many central merchants supported it, according to Statesman reporting at the time.

“There was a feeling that malls were this huge generator of traffic, both local and tourist,” said Bob Aldridge, a lawyer and former chairman of the Boise Historic Preservation Commission. “They saw that as this huge economic thing that would just boost Boise.”

American shopping malls had their heyday after World War II. Most U.S. states opened their first mall during the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s. Several cities pursued indoor shopping centers downtown, where central business districts were declining in popularity.

Kiwanis Magazine, reporting on the downtown mall trend in 1961, hailed shopping malls as the “beautifier of cities” and a solution to the “deterioration” of urban life driven by traffic jams and “grimy” downtown buildings.

Boise’s downtown was “looking over the edge of abyss” if city planners didn’t come up with a central mall plan before one popped up in the suburbs, a Los Angeles consultant told local officials in 1965, the same year the Boise Redevelopment Agency was founded.

Over the next decade, the urban renewal agency acquired downtown properties and leveled buildings to make way for redevelopment. At various times, plans called for the demolition of the Alexander, Idaho, Simplot and Fidelity buildings as well as the Union Block, the Romanesque Revival strip along Idaho Street with a gray sandstone facade that’s home to Moon’s Kitchen Cafe.

But actionable mall plans were slow to materialize, giving historic preservation groups time to organize in opposition to the destruction of historic buildings, the Statesman reported in 1974.

Historic icons lost to redevelopment

The Boise Redevelopment Agency’s aggressive use of the wrecking ball gained national attention in 1974, when Boise native L.J. Davis published an article in Harper’s Magazine entitled “Tearing Down Boise.”

“If things go on as they are, Boise stands an excellent chance of becoming the first American city to have deliberately eradicated itself,” Davis wrote at the time.

Locally, the Save Old Buildings Association and Preservation Idaho lobbied against demolishing historic sites, like Boise’s Chinatown. Founded in 1901, the laundry and restaurant district “provided services and connections” for Boise’s Chinese residents and “planted memories of a distinctively different culture in the minds of many other residents,” wrote Ann Felton in an urban studies report for Boise State University.

Aldridge was an Idaho Supreme Court law clerk when justices considered whether the Boise Redevelopment Agency could condemn the Hop Sing Tong building, one of Chinatown’s last remaining structures.

The owners of the building fought its destruction in court, and Hop Sing Tong’s last resident, Billy Fong, a former cook at Chinatown’s most popular restaurant, Shanghai-Low Cafe, refused to leave until the wrecking ball arrived, the Statesman reported at the time.

Aldridge said he felt “a tremendous sense of guilt” for his role in the court’s decision allowing the Hop Sing Tong building to be destroyed.

“It would have been wonderful to preserve Chinatown in Boise, along with other things,” Aldridge said by phone.

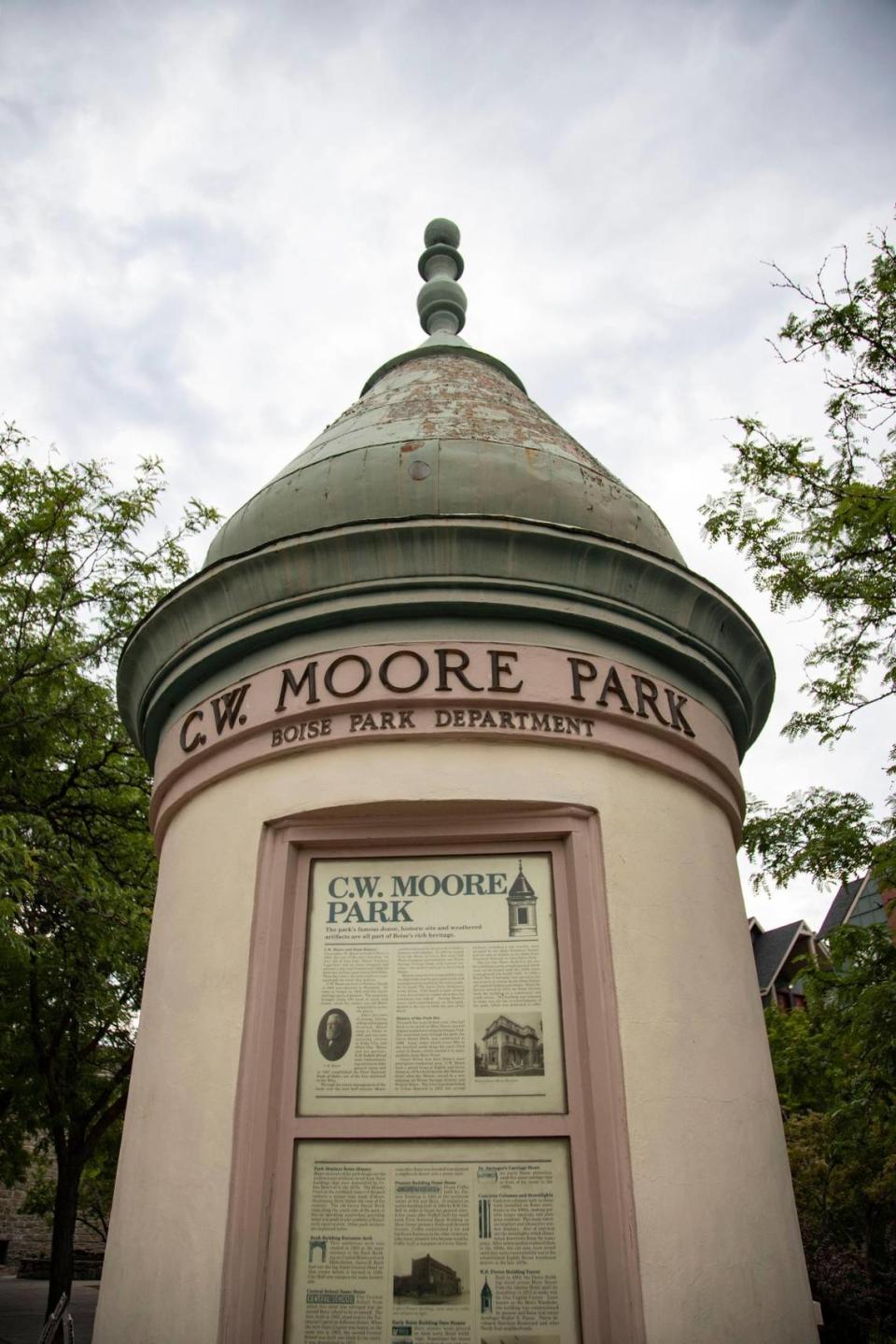

Downtown Boise’s C.W. Moore Park displays artifacts from buildings demolished during the urban renewal era, including a turret from the W.E. Pierce Building, torn down in 1975, and the name stone from the Central School, demolished in 1973.

Aldridge later joined the Historic Preservation and pushed for tax credits and other financial incentives to restore aging structures rather than destroy them. Urban renewal loans financed a remodel of the Alaska Center in 1983. The Alexander and Hoff buildings were also refurbished in addition to the Egyptian Theater and Jefferson Place, which all remain standing today.

“We did save some things that wouldn’t have been saved,” Aldridge said. “We got some changes made, and I’m happy about that. The losses hurt … but it’s over and done.”

Mall plans abandoned, downtown reenergized

Winmar Co. abandoned its mall plans in 1983, after struggling for years to secure commitments from department stores to anchor the shopping center.

J.C. Penney Co., The Bon Marche and Montgomery Ward & Co. had each expressed interest, but a competing suburban shopping center proved more attractive. The Boise Towne Square mall opened in 1988.

Winmar Co. President Frank Orrico also blamed Boise residents’ persistent skepticism for the failure of the downtown mall.

“The whole community must shoulder the blame,” Orrico told the Statesman in 1984. “There was always somebody with sufficient authority or clout raising a question in the press.”

Boise ultimately did get a downtown shopping center, although on a much smaller scale. After a decade of construction stagnation — which left the area “studded with debris-littered lots where decaying buildings once stood,” as a Statesman editorial put it — construction began on Capitol Terrace in 1988.

Today known as Main and Marketplace, the two-story, open-air retail building that takes up about half of a city block is home to Rediscovered Books, Stella’s Ice Cream and other popular stores and eateries. The historic Falks Building was destroyed to make way for the shopping center and next-door parking garage, but many considered the aging structure beyond preservation, according to Statesman reporting at the time.

Bars, restaurants and shops within the boundaries of the original mall plans bustle with activity today. Business Insider recently called the area surrounding Eighth Street the “coolest neighborhood in Idaho.” The Grove Plaza, the Boise Centre and the Grove Hotel attract locals and tourists where Chinatown once stood.

Travel blogs regularly rank Boise’s downtown among the most attractive in the country. It’s No. 6 on Livability.com’s “Top Downtowns,” and No. 19 on Attractions of America’s “Top 20 Best Downtowns in the USA” alongside New York, Chicago and Savannah, Georgia.

Meanwhile, the number of indoor shopping malls in the U.S. has dropped from roughly 2,500 in the 1980s to about 700 today, and it’ll likely continue to decline, the Wall Street Journal reported last year.

“It would have been a disaster,” Carley said of a downtown mall. “It would have kept downtown from being as great as it is.”

Carley credits the city of Boise, the Capital City Development Corp. and the Downtown Boise Association for reenergizing the area in recent decades.

“It’s interesting to walk anywhere because the architecture is interesting,” Carley told the Statesman by phone. “It’s very walkable, it’s compact, it’s vibrant, it’s lively. This whole community is proud of its downtown, and it shows.”