Doyel: Baseball needs more days like this, so we can remember why we fell in love

Baseball can make it so hard to like baseball, and you know what I mean.

Sorry to get all “old guy” on you, shouting those dadgum kids off the lawn, but baseball has an image problem – a popularity problem – of its own making. It’s the defensive shifts and pitch counts and unwritten rules and the cheating, cheating, cheating. Maybe they cheat as much in other team sports, but say this for baseball: None has mastered the art of getting caught like our national pastime.

So people like me, people who grew up loving the game the way birds love the open sky, we’ve fallen out of love.

Hell, some days I don’t even like baseball anymore, and I played to age 18, almost played in college, did play in a semi-pro league at 23, and covered the Florida Marlins for The Miami Herald from 1995-97. I was there the night Edgar Renteria grounded a soft single with two outs in the 11th inning of Game 7 to beat the Cleveland Indians for the 1997 World Series.

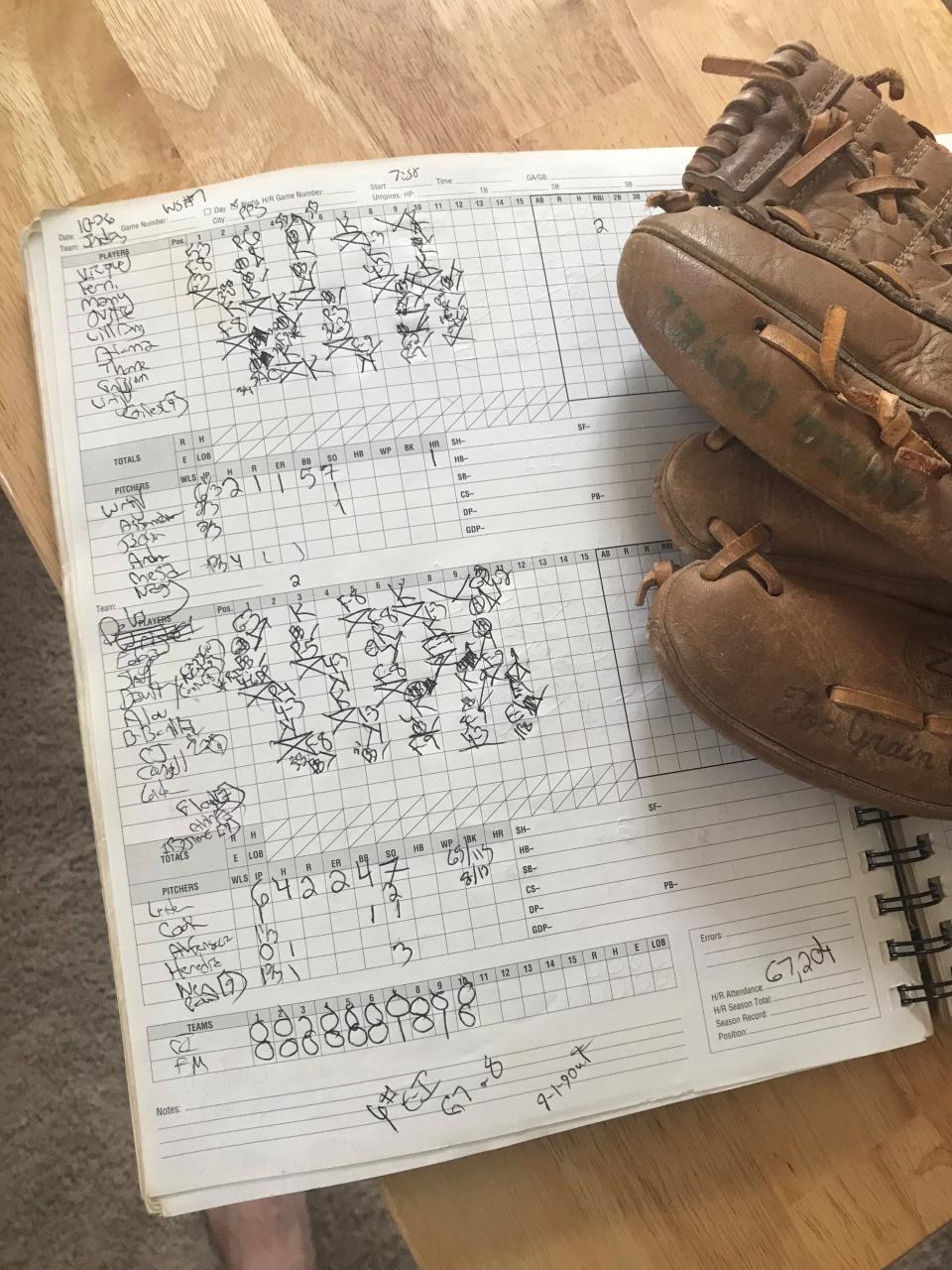

Still have my scorebook from that 1997 season with sloppy, hand-written play-by-play that I’m seeing ended one batter before Renteria’s single. Says here Devon White grounded into a 4-2 fielder’s choice for the second out in the 11th, and it stops there, and now I’m remembering why: Because Renteria’s hit ended it, and the deadline to file the most important game story of my life was that second.

But I can still see the flashbulbs exploding all over Pro Player Stadium, like lightning striking or lightning bugs loving or maybe a bit of both.

Feel those chills on my arm? That's from remembering the way it used to be.

Something happened along the way to me, to lots of us, but every now and then baseball can have a day that brings you back. It happened Saturday.

And then it happened again.

Because I’ve long given up watching baseball on television, I get everything I need from ESPN, from the highlights on SportsCenter. Watching on Sunday morning, I saw what had happened Saturday. And then what else had happened. And then I got up, arms tingling, and rushed to the keyboard to write this story.

Could this be the last love story I ever write about the game that raised me? Hope not. I’ve missed these chills.

Bryce Harper forgives Blake Snell

It’s Bryce Harper’s broken thumb. That was the first thing that moved me, and before you get mad, understand: It was what happened next. Not the actual pitch from San Diego’s Blake Snell, a 97-mph fastball that came up and in, a little too much in each direction, and crashed into Harper’s left thumb.

Right away, two things happen:

Harper drops to a knee in pain, then walks toward the clubhouse. He’s shaking his hand and shouting at the pain, at the bad luck, at Snell. He’s furious, and you understand why. The other thing that happens is on the mound, where Snell is grimacing and wincing and taking several steps toward Harper, to check on him, to mouth words of apology.

Normally, and this is one of the many, many things that have made me lose interest in the game, pitchers who hit a batter give him a dead eye. They didn’t mean to do it, not usually, but they’re not about to show vulnerability, weakness, humanity. Get in the batter’s box against me? You get what you get. The pitcher holds up a glove, wanting another ball from the umpire. Who’s next?

Not Snell. He's known Harper since they were young kids, competing on the West Coast amateur scene. Snell is crushed.

Harper knows this, down deep, but he’s walking off the field and screaming at Snell for the reckless pitch. Harper isn’t thinking clearly, and again, you understand.

Snell is gesturing to him, pleading with his eyes, and Harper comes back to reality. Now he’s shouting back, “I know you weren’t trying to do it,” and he’s tapping his own chest, his own heart, and don’t ask me why my eyes are filling as I write this. Maybe because Snell is walking back to the mound, still miserable, wiping the moisture from his face. Not sure that was all sweat.

What happened Saturday at Petco Park was what our baseball coaches told us about the game, that it would teach life lessons. We’re seeing one right now, a lesson on forgiveness. Can’t remember the last time we’ve seen such a lesson on a Major League Baseball field.

Baseball rescued nerdy 'Greg' Doyel

Can you smell the leather of a baseball glove, even now? Same.

As a kid, walking around downtown Oxford, Miss., I’d go into Wilson Sporting Goods on “The Square” just to see the gloves on the wall, studying the various webbings and hues of brown, checking for new left-handed mitts. There might be just one glove in the whole store for a lefty like me, but I’d find it and put it to my face and inhale. You might think that’s weird, but only if you didn’t play. The rest of us, we know.

Baseball was playing catch in the backyard with my dad after work, or with my mom after their divorce. Baseball was waiting nine months for Little League baseball season, and then every year, before the first game, running out back to practice my pop-up slide.

Baseball was taking infield and batting practice, and hitting the first ball of my life over a fence, a 200-foot rainbow down the right-field line at age 12. It was in practice, but I remember the thrill even now. For years I refused to throw away that 30-inch, 27-ounce bat, that Easton “Black Magic.”

More Doyel on baseball:

Youth baseball in Oxford was segregated in 1978. Here's what my dad did.

'Greatest game ever pitched' starred Sandy Koufax ... and my high school coach

There were 10 home runs in actual games, and I remember each one, but the second-most memorable “home run” of my life also came in practice. It was years later, at Stratford Academy in Macon, Ga., my sophomore year. I was the new kid as usual, following my dad from city to city, and I was not popular. Uncool hair I kept it in place with three coats of hairspray, thick glasses, shy, uncertain.

Nobody on the baseball team knew who I was, including the coaches, until practice started. Stratford was the defending state champion, a baseball powerhouse, and I was hoping to make the junior varsity. That first week of practice, in a simulated game, four-eyed little Greg Doyel – the second ‘g’ came two years later, when the Macon newspaper misspelled my name and a girl named Mary May liked it – hit a home run off the scoreboard in right, against a freshman named David Mann.

Now people knew who I was. I still remember Ronnie Goldman, a football player, the most popular kid in our class, approaching me in the hall and asking: “You hit a ball off the scoreboard?”

Ronnie became my best friend. Great kid. Baseball introduced us.

I’ll be damned, I started for the varsity that year. Batted ninth, played right field. We won state my sophomore season, and again when I was a junior. Batted leadoff, the smallest first baseman you ever saw. I had the game-winning hit in the state championship game if you can believe that, a bases-loaded double. Tie game, two outs, fifth inning. Outside pitch. Poked it into left-center.

Senior year, we lost in the state quarterfinals. I made the final out of the season. Down four runs, bases loaded. Fly ball to right. Still hurts.

This is what you remember.

This is why you get disappointed, at what baseball has become.

Beau Dowling: home run of a lifetime

It used to be a game of numbers, and they were magical. Batting average, home runs, RBI. George Foster of the Cincinnati Reds was my favorite player, and in 1977 he hit .320 with 52 home runs and 149 RBI. Didn’t have to look that up. If you grew up a baseball fan, you have your own numbers to remember.

Ron Guidry wasn’t my favorite pitcher – that would be Tom Seaver of the Reds, then Phil Niekro of the Braves thanks to TBS – but Guidry was 25-3 with a 1.74 ERA in 1978. I remember those, too. How could you not?

Baseball is still a game of numbers, but now they’re just so cold. Listen, intellectually speaking, I understand the value of OBP and WHIP, and while the math behind it is gibberish to me, the concept of VORP makes sense. But numbers like that have changed baseball from a game you understood in your heart to one you understand only with a calculator.

And I hate calculators.

Do I hate baseball? No, but it makes me sad when Dodgers manager Dave Roberts removed Clayton Kershaw with a perfect game through seven innings because it was early April and he’d thrown 80 pitches. Again, intellectually speaking, I understand the move, the injury risk. Don’t be condescending like some number-crunchers can be, and confuse sadness with stupidity.

Most of us who’ve fallen out of love with the game, we understand the defensive shift. But here’s what’s wrong with it: At its core baseball is a numbers game, players from one generation to another compared by hits and batting averages and the like, and the shift taints those comparisons. Mike Schmidt, a dead pull hitter, never faced a shift. Every time Los Angeles' Shohei Ohtani grounds out into short right field, an angel loses its wings.

Lots of reasons to be discouraged by the game. All these unwritten rules, like “showing up” a pitcher by daring to enjoy the sight of your home run. Or this one: Being unable to steal a base when your team is way ahead.

Comebacks can and do happen, but the unwritten rules frown on the winning team trying too hard in a blowout; at a certain point, only the losing team is allowed to try. Afterward the losing manager, an old guy like Buck Showalter or Tony La Russa, someone who takes himself so seriously it’s actually uncomfortable, will say something stern.

Too many benches clearing, too many pitching changes, too many 3½-hour games. The baseballs are juiced this year, but not next year. The players are juiced every year. You don’t know that, but you know it, and it’s another reason not to care.

But then Blake Snell hits Bryce Harper and is wiping moisture from his eyes after Harper forgives him, right there in front of God and teammates and 37,467 fans.

And then, somewhere else in America, we get more magic:

It’s Saturday in Chicago, the Baltimore Orioles in town, and a 7-year-old boy named Beau Dowling is about to hit the home run of a lifetime. Dowling has beaten cancer once, but it’s come back. The Chicago White Sox organization is giving him a gift, inviting him onto the field to swing the bat and circle the bases, but now it’s not merely an organization giving him this gift. It’s players from both teams, the Orioles lining the first-base line and the White Sox the third-base line, leaning way down to give Beau Dowling a fist to bump or a palm to slap as he rounds the bases.

This is a piece of baseball you’ve never seen, yet it’s baseball like you remember. It’s kids and adults and happiness, and maybe there’s a few tears as well, but as Beau Dowling heads for home you’re a child or a dad, and baseball is again perfect.

Find IndyStar columnist Gregg Doyel on Twitter at @GreggDoyelStar or at www.facebook.com/greggdoyelstar.

This article originally appeared on Indianapolis Star: Perfect game: Harper accepts Snell apology, Beau Dowling rounds bases