Dozens of convicted murderers to get a new chance at parole in KY after policy change

Several convicted murderers who had been ordered to spend the rest of their lives behind bars will get another chance at leaving prison under a policy change by the Kentucky Parole Board.

Under the old rule, the board sometimes issued a “serve out” order at the first parole hearing for people serving sentences of life or life without the possibility of parole for 25 years.

Inmates are eligible for a parole hearing after 20 years on a life sentence.

An order to serve out meant the person would never get another parole hearing, dying in prison absent a court decision changing his or her conviction or sentence, or a pardon or commutation.

Last month, the board changed the rule to say it would no longer issue serve out orders at the first parole hearing of inmates serving sentences of life or life without parole for at least 25 years, though it could still do so at their second hearing, according to the Department of Corrections.

The board applied the change to several people who had already been ordered to serve out a sentence, many years ago in some cases.

For instance, the board issued a serve out to Clawvern Jacobs in 2002, but he will be eligible for a new hearing this year based on the new rule.

Jacobs, now 74, was convicted of kidnapping Judy Ann Howard, a student at Alice Lloyd College in Knott County, sexually abusing her and then beating her to death with rocks in 1986.

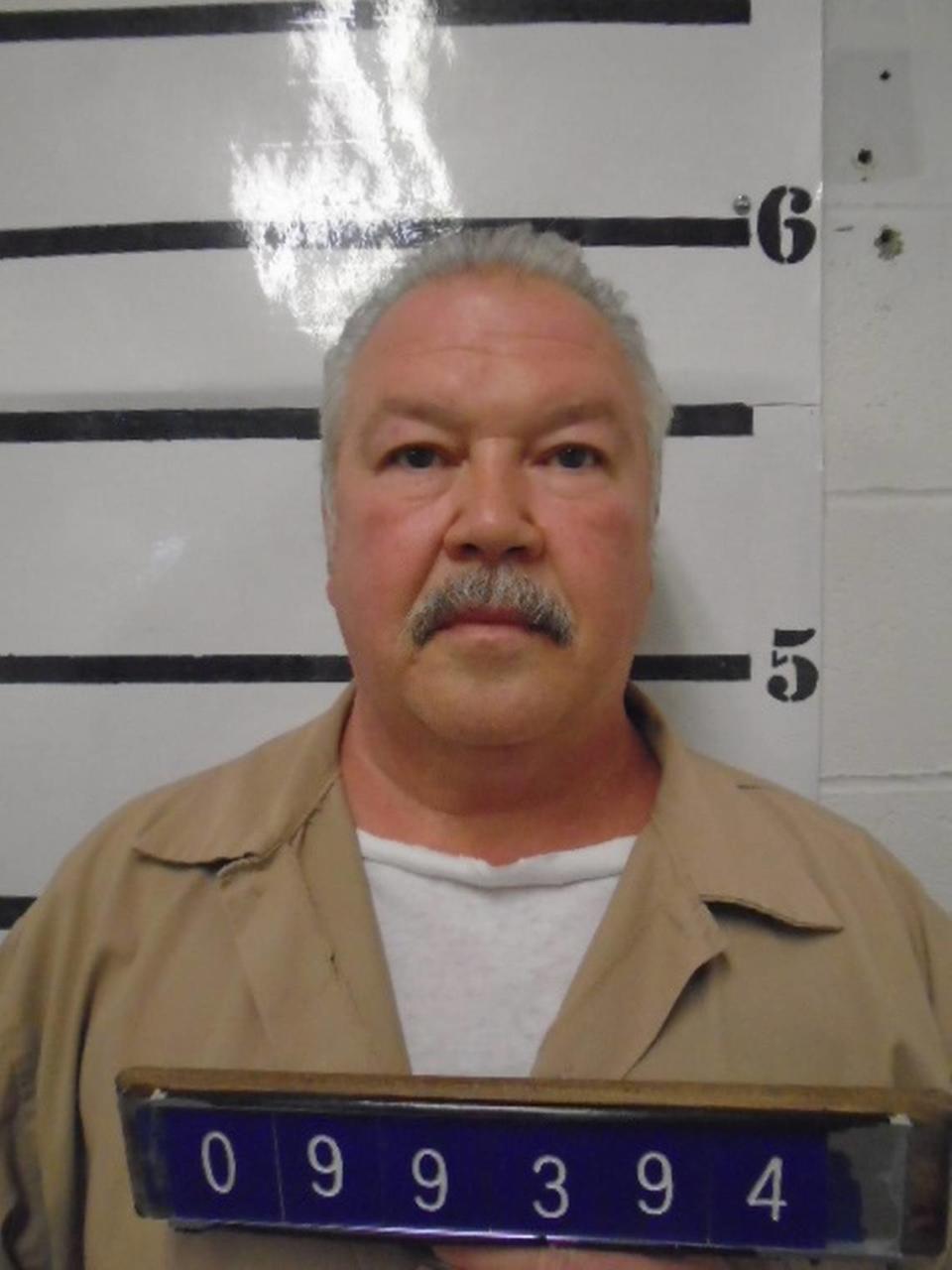

Another example is George E. Wade, convicted in the notorious kidnapping, robbery and murder of two Trinity High School students in Louisville in September 1984. His co-defendant, Victor Taylor, is on Death Row.

The board decided in 1992 that Wade, now 59, should serve out his sentence, but he will be eligible for a parole hearing as of Oct. 1 under the new policy.

Policy change affects 45 inmates

There are 22 inmates who will be eligible for a new parole hearing this year despite earlier decisions that they should stay in prison for the rest of their lives.

For 23 others who received serve out orders in the last few years, the board said they will be eligible for a new parole hearing 10 years after that initial order.

Others eligible for a new hearing include Donald Bartley, who took part in the murder of Tammy Dee Acker, a University of Kentucky student stabbed to death in Letcher County in 1985; Stephanie Spitser, who strangled her 10-year-old stepson, Scotty Baker, to death in Clay County in 1992 and then set his body afire at an abandoned strip mine; and Leif Halvorsen, who was sentenced to death for taking part in killing three people in Lexington in 1983.

Then-Gov. Matt Bevin commuted Halvorsen’s sentence to life in December 2019, making him eligible for a parole hearing last year.

The board issued a serve out to him, but he will get another hearing in 2030.

The change doesn’t mean any of the inmates will get out of prison. The Parole Board could deny them release again.

But prosecutors decried the change, saying the Parole Board issued the new policy without notice, blindsiding them and family members of crime victims who believed they would never again have to deal with the potential for a convicted murderer to get out of prison.

“Now to open that wound back up is simply unconscionable,” said Chris Cohron, commonwealth’s attorney in Warren County.

Cohron has several cases affected by the ruling, including those of three gang members who took part in the execution-style killing of a mother and father. The gang also shot their daughter but she survived.

‘I think it’s a bad decision’

Prosecutors said it wasn’t right for the Parole Board to adopt a new policy without taking public comment and absent legislative action.

“Now they get to worry that they’re going to have to fight the whole parole issue again,” David Dalton, commonwealth’s attorney for Pulaski, Lincoln and Rockcastle counties, said of victims’ families. “I think it’s a bad decision.”

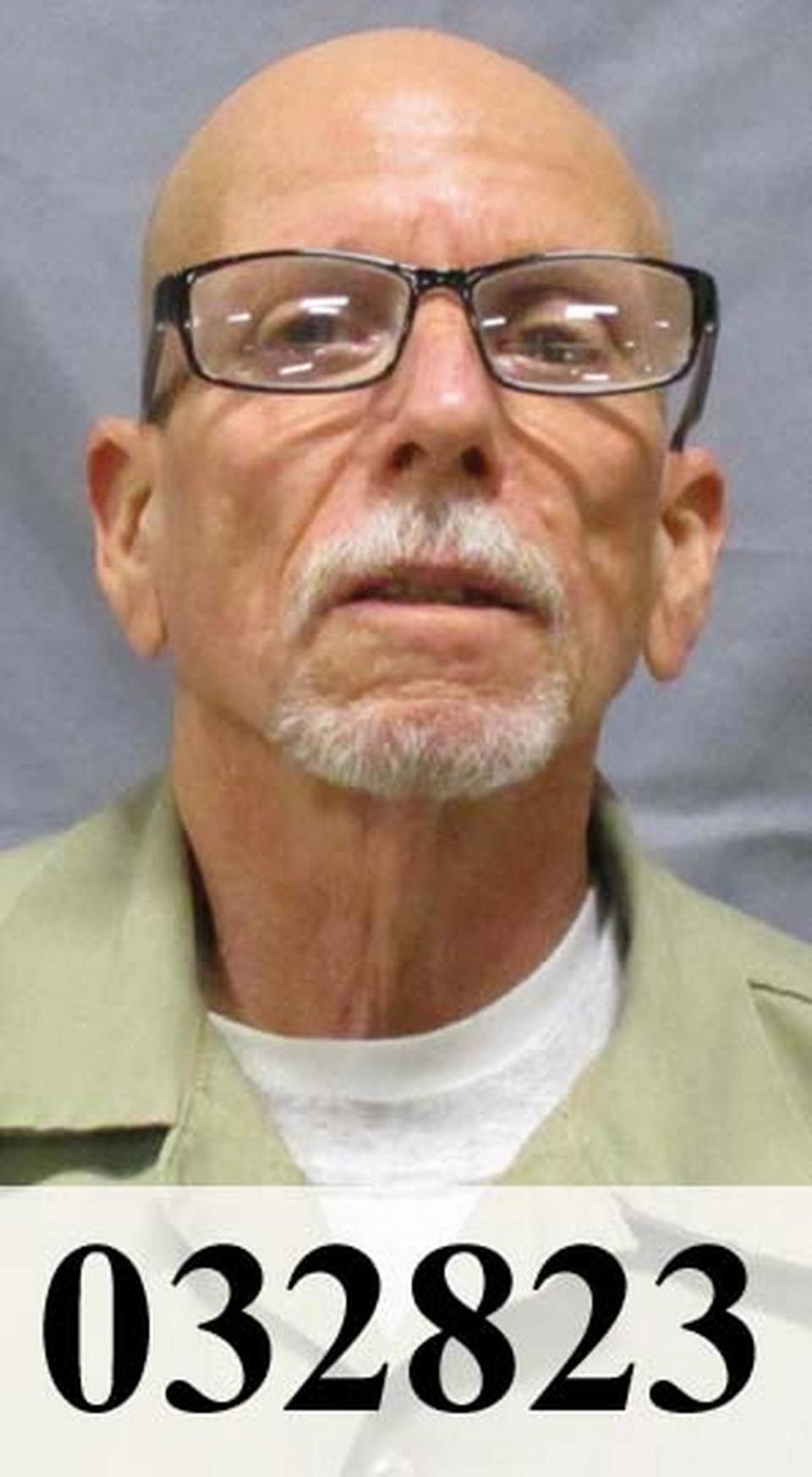

In Dalton’s circuit, the new policy affects Jeffrey B. Coffey.

Coffey, now 50, was convicted of murdering Taiann Nicole Wilson, 15, and Matthew Coomer, 17, while they were on their first date in rural Pulaski County in 1985.

Coffey encountered the two at a creek, shot Matthew in the chest and then stabbed Taiann at least 100 times. Coffey’s attorney argued he had mental disorders.

Coffey was sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole for 25 years.

As Coffey’s parole eligibility approached last year, family and friends worked hard against his release, gathering almost 10,000 signatures on a petition.

The Parole Board ordered him to serve out his sentence in June, but he will now be eligible for another hearing in 2030.

Members of the teens’ families said it wasn’t right for the Parole Board to undo its earlier decision.

“It’s overwhelming that we’re gonna have to face this again,” said Tonya Baumgardner, Taiann’s older sister. “It’s very difficult, very traumatic, for the families to relive it.”

Prosecutors said the change runs counter to Marsy’s Law, a measure state voters have twice approved to give victims more rights, prosecutors said.

“Victims’ families seem to have been simply forgotten about, as far as we can tell,” said Brian Wright, commonwealth’s attorney for Casey and Adair counties.

Wright said the change will mean a new parole hearing for Johnny Allen, who shot his wife to death in 2000 and then set their house on fire.

Wight said he hoped Attorney General Daniel Cameron would look into whether the Parole Board made the change lawfully.

Change prompted by lawsuits

The Department of Corrections said the change was a response to legal challenges and an effort to head off further litigation.

Timothy G. Arnold, director of the Post-Trial Division at the state Department of Public Advocacy, said the department is representing a number of inmates in lawsuits over how the Parole Board handles cases.

In one, a group of inmates argue that there are a number of problems, including that the board doesn’t require members to use a risk and needs assessment of inmates by the Department of Corrections in making parole decisions, and that there is not an adequate process for inmates to request reconsideration of a decision.

That complaint also argues that it is unconstitutional for the board to issue a serve out that turns a sentence of life, or life without parole for 25 years, into something greater — effectively a death sentence.

The Parole Board doesn’t have legal authority to issue serve outs, removing parole eligibility in cases in which the legislature and courts have said people would be eligible for parole, the lawsuit argues.

The Parole Board has said in response that its procedures and decisions are sound, and that it does have authority to keep people in prison the rest of their lives.

“The length of deferments is not based on a whim,” the board said in one document.

In a ruling in that case last year, Franklin Circuit Judge Phillip Shepherd said he disagreed with the argument that the Parole Board does not have authority to issue serve outs, citing a precedent.

Attorneys for the inmates have asked the state Supreme Court to review the issue of serve outs.

In a motion asking to participate in the lawsuit, former Supreme Court Justice Bill Cunningham and Robert G. Lawson, a longtime University of Kentucky law professor who is an authority on the state’s criminal code and rules of evidence, called serve out decisions unconstitutional.

‘A burst of hope’

Only judges and juries can hand down a sentence of life without parole, and only in cases with aggravating circumstances that would have qualified for the death penalty, their motion said.

The Parole Board has imposed such sentences for crimes that didn’t qualify, Cunningham and Lawson said.

Cunningham said his interest in taking part in the case was his observation of “the injustice of the draconian penalty of ‘serve out’ on life sentences,” imposed by political appointees with no judicial oversight.

Arnold said the Parole Board’s new rule on serve outs was a good step, though it didn’t go far enough.

“All those inmates who found that their parole eligibility was reinstated were given a burst of hope and a possibility of a future outside of prison walls — an opportunity that they thought was over for them,” Arnold said in an email.

The sentence of life without parole is “one of the worst criminal justice policies imaginable,” Arnold said, because it takes away discretion to release someone from prison “precisely at the moment society would most like that discretion to be used — when the inmate is old, infirm, costly, and a risk to nobody,” Arnold said.

Arnold said serve outs had not been reserved for the worst offenders, but have been ordered for some people who did not commit homicides.

The experience of defense attorneys is that the Parole Board orders serve outs for people who did not impress the members in a hearing, “and are now expected to pay for that with their lives,” Arnold said.

The Parole Board issued an average of three serve outs a year from 1992 up to 2020, but had done 19 in 2020 by November, pointing up the need to address the issue, according to the inmates’ lawsuit.