Dr. Julie McKay: Supporting Jacksonville's unhoused with OCD, other mental health issues

I glanced at the clock hanging in the hallway. Only three more patients to go before the lunch break. I desperately needed my daily dash to the safety of my COVID-free car, so I could rip off my N95 mask and breathe deeply. This is the pattern of my day as the lead physician at the unhoused shelter in my town.

Finding commonality

The next patient up was “Carlton.” As I entered the exam room, I saw that Carlton had tried. His matted hair had been patted down to a semblance of order. He had turned his worn T-shirt inside out to the less dirty side. Carlton had probably not had the benefit of a shower for months in the Jacksonville heat. Still, he was a person in need of care. I shook his hand and made eye contact.

I ask gentle questions to find a thread of commonality as we began our relationship. How did Carlton become so depleted? My curiosity is a daily checkpoint, ensuring I am not headed down the same path. Every story is different, but being unhoused can happen to anyone.

Carlton's story

Carlton began telling me about his past. He was the former CEO of a Fortune 500 company. He flew on private corporate jets and had a yacht. Carlton even showed me a wrinkled picture of his beautiful ex-wife and two children. The kids wore matching designer outfits, and Carlton wore pink shorts with little green whales. He described his mansion, zero-edge pool and his fleet of cars.

So, what happened?

Carlton continued his sophisticated life story, telling me how the pressure at work was very intense. His kid needed an expensive tutor, and both of his parents died unexpectedly, leaving him the self-assigned leader of both extended families. One evening he got carjacked. And after this happened, he started scrubbing his hands and washing everything around him. The long-suppressed obsessive-compulsive disorder (commonly referred to as OCD) tendencies from his youth roared back to life and devoured him like a lion.

Ramifications

This odd and unexplained behavior freaked out his naïve young wife. She bolted with the children to a different CEO and remarried once their divorce was complete. Carlton's career faltered. He could no longer make decisions. All the while he cleaned his office space obsessively. Eventually his company fired him.

'Housing state of emergency': Jacksonville City Council wants more debate on affordable housing bill

Community health assessment: Nagging issues, inequities, opportunities for action in Jacksonville area

Letters: Millage increase was right thing to do, but more needed to end teacher exodus

Of course, one by one, everything he worked for evaporated, and Carlton found himself living on the street. It was probably the worst situation for an OCD sufferer struggling with contamination triggers. The mobile shower van broke or did not show up. As with others living unhoused, he found it challenging to take a bath in the public library sink. Without the ability to keep clean, he deteriorated physically, mentally and spiritually.

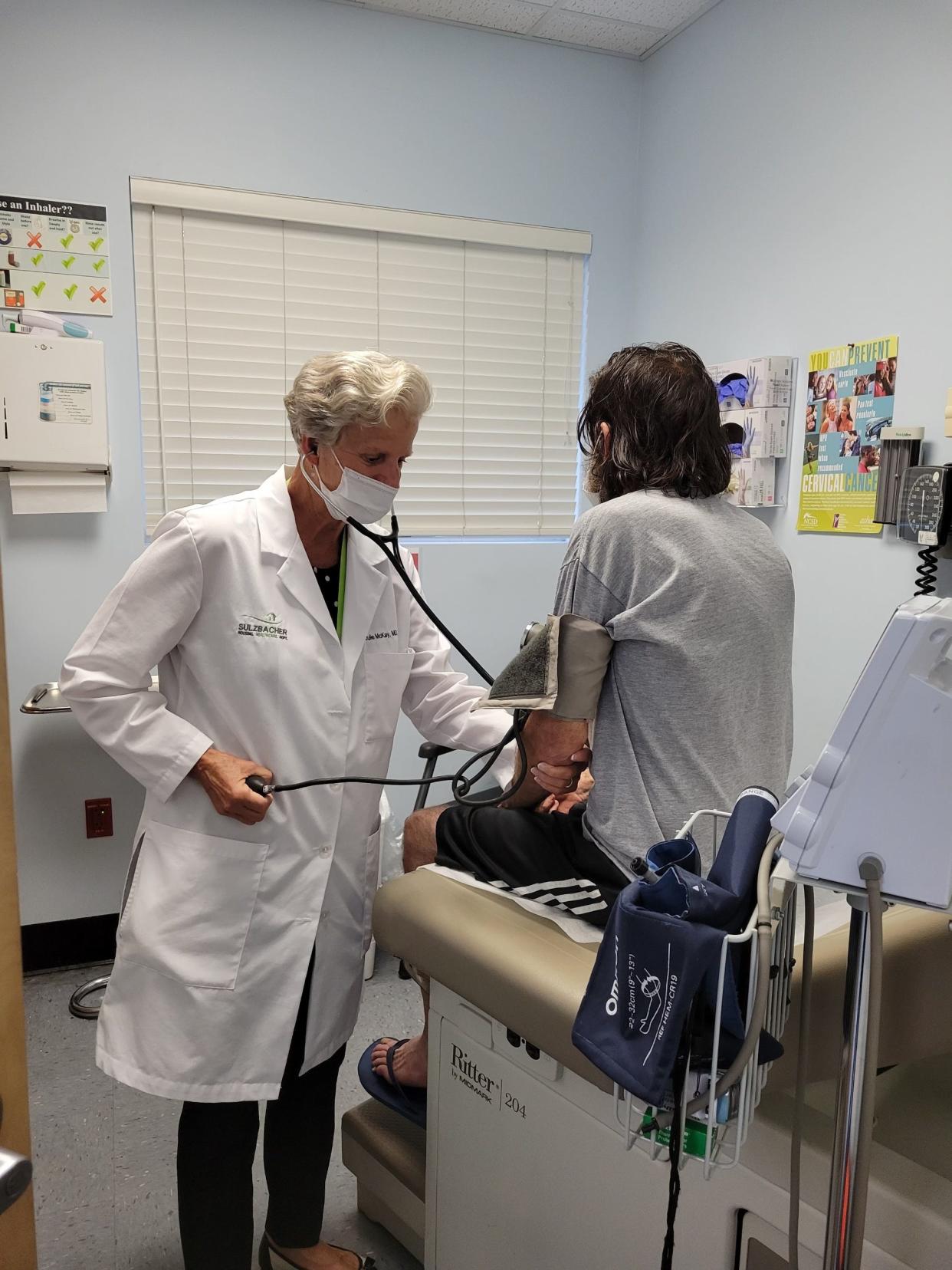

Medical exam

I listened as he recanted his fall from superstar status. His family disowned him; he had not seen his children for two years. Then we plowed through the medical questions, the exam and the treatment plan.

I promised we would see each other in a month. I promised to try to figure out housing, a stable food source and better shower access. And to my surprise, Carlton reached over and hugged me quickly. It felt like we had won a minor victory in the trust game.

I finished up the morning patients, but Carlton weighed heavily on my mind. I raced to my car and ripped off the N95. By the time I reached my sanctuary, I was sobbing. Some of the tears were of profound gratitude to the Lord for sparing me from Carlton's grief and pain. But mostly, I was just overwhelmingly sad.

Weary community systems

I failed Carlton that day. The weary community psychiatry system and medical community failed Carlton too. I had nothing to offer him through this OCD crisis except an occasional shower and a clean T-shirt. It was woefully too little.

In Duval and Clay counties combined, there are approximately 1,222 unhoused people at any given time. Of these, a large percentage suffer from mental illness. It is a catastrophic burden on a community to provide adequate care for unhoused people who are also suffering from mental illness. We must do better as a society to provide affordable, available mental health care. Doing so will prevent drastic downward spirals like Carlton's.

Ironically, if Carlton had suffered from one of many other life-threatening illnesses, I would have had ready access to offer treatment. Cancer, coronary artery disease, diabetes and HIV/AIDS all have adequate funding available. Why is his OCD treatment underfunded and limited in availability?

We must do more

You might think OCD is not life-threatening. I suppose it is not typically fatal to the human body, but Carlton is a dead man walking. We must do more to help unhoused people, support legislation that improves funding and access to therapies and training for OCD, such as exposure and response prevention treatment. Lastly, we must not continue to fail Carlton. The burden is ours.

Julie McKay, MD, is the lead physician at Sulzbacher Clinic in Jacksonville. She also serves as a board member of JACK Mental Health Advocacy, a nonprofit organization created to support families of sufferers and advocate for treatment for people suffering from OCD and anxiety disorders.

This guest column is the opinion of the author and does not necessarily represent the views of the Times-Union. We welcome a diversity of opinions.

This article originally appeared on Florida Times-Union: Supporting the unhoused in Jax with OCD, other mental health issues