Drake released a surprise dance album, 'Honestly, Nevermind'

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

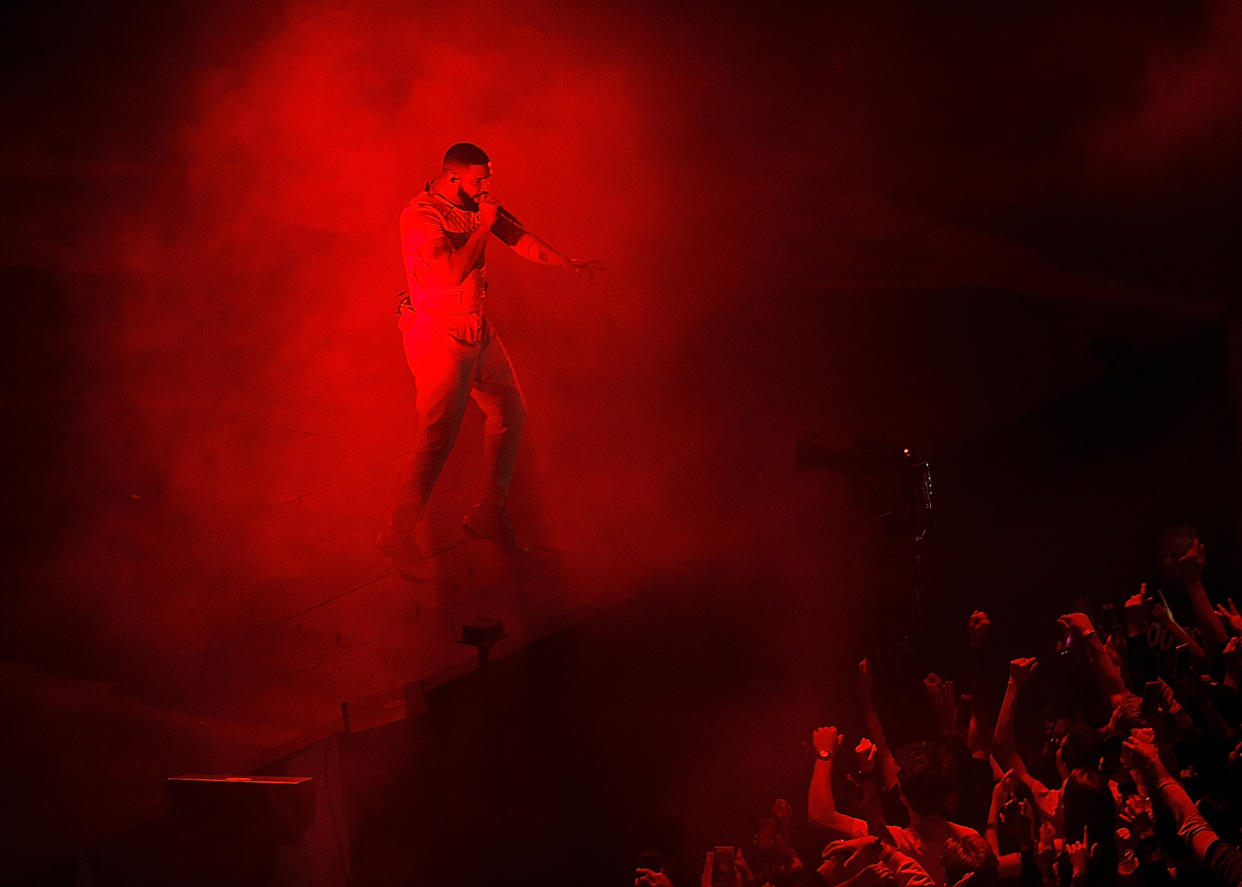

Drake surprised fans last week with news of his seventh studio album, titled “Honestly, Nevermind.”

Even more surprising was the album itself.

A far cry from its multiplatinum predecessor, “Certified Lover Boy,” which dominated hip-hop and rap charts alike last year, “Honestly, Nevermind” marks Drake’s first substantial push into a new genre: house music.

While fans are divided over the experimental 14-track offering, it’s showing signs of commercial success, breaking Apple Music’s record for highest first-day streaming of a dance album after its release Friday.

Drake, 35, whose given name is Aubrey Graham, has flirted with house music in the past, most notably in 2018’s “Scorpion,” and 2017’s “More Life.” The albums borrowed sparingly from tech house, Jersey club and Afrobeats, among other genres, to complement traditional hip-hop tracks.

With “Honestly, Nevermind,” Drake, of Toronto, commits entirely to the sound, releasing an album that predominantly features influences outside of hip-hop.

The album credits a slew of big-name house music producers, like Black Coffee, a South African DJ who has worked with David Guetta and Usher, and it’s noticeably light on features from other artists. Instead, Drake leaves ample time for lush, club-ready music to play at length, occasionally budding in to sing-rap melodically over the beats.

“I let my humbleness turn to numbness at times letting time go by knowing I got the endurance to catch it another time,” Drake wrote in the album’s Apple Music description. “I work with every breath in my body cause it’s the work not air that makes me feel alive.”

He said the album is dedicated to the late fashion designer Virgil Abloh.

Across social media, the album quickly ignited discourse about the genre of house music, with many people expressing astonishment that a rapper would gamble on a genre not typically associated with hip-hop or Black audiences.

But Drake’s foray into house music isn’t exactly novel.

House music has its roots in Black culture, with rappers like Azealia Banks achieving mainstream success in the genre within recent years.

Before Banks, house music was a staple in Black communities — and especially Black, gay communities, where scholars say the genre was born.

House music’s origins

House music gained prominence in the late 1970s as disco began to fade in mainstream popularity and club DJs in Chicago and New York began to explore creative ways to edit, mix and remix old disco records.

“People were in their basements having basement parties and dancing to music,” said Brian Harlan Brooks, a New York-based choreographer and dance educator. Brooks grew up with house music and incorporates it in his teaching. “What they were doing was laying beats over top of pop records.”

Brooks recalled early DJ innovators like Frankie Knuckles, Larry Levan and DJ Ron Hardy bringing the new sound — high-tempo beats fused with symphonic diva vocals — to underground Black and Latino gay clubs.

“I would save up all my little money for the week, and I would make my way over to Christopher Street where the bars were,” Brooks said of his first experiences hearing house music. “I was 15, so I’d have to sneak in, and when I got in, I’d start hearing house music.”

Brooks said it was music designed to make you dance. And dance they did — Brooks recalled stories of his and his friends dancing from 12 at night till 12 in the morning, then going home soaking wet with sweat.

“It was directly coming from the heart like a heartbeat, and that heartbeat was wrapped around vocals and polyrhythms and mixed in with a little gospel,” he said. “Something about the music felt like church and sin all at the same time. It was freeing”

The term “house” is believed to have come from The Warehouse, a Chicago club with a mostly gay clientele at the time. It was where DJ Frankie Knuckles held residency. Knuckles is often credited as the godfather of house music.

By the 1990s, the work Knuckles and other DJs put into developing house music led the genre to attract mainstream attention, with artists like Madonna co-opting the sound for her 1990 hit “Vogue.” The same year, “Paris Is Burning” hit theaters, the flashpoint documentary shedding yet more light on house music within Black and Latino ballroom culture.

“It grew because people loved it,” Brooks said. But as house music grew, Brooks added, Black DJs could no longer afford to keep up with the equipment and the new techniques needed to be competitive with major record labels that were pumping tons of money into the genre. In addition, many of patrons of New York’s and Chicago’s ballroom scenes were kept out of the venues where the music was starting to be played.

By the 2000s, hip-hop and reggae began to take over gay clubs, while house music began to cater to white and European crowds.

Artists like Calvin Harris and Avicii began playing house music at high-end dance clubs in cities like Ibiza, Spain, and London.

House music’s future

Brooks said he has been paying attention to the online chatter about “Honestly, Nevermind.” He isn’t surprised that many people were unaware that house music and Black culture have always been intertwined.

“Gospel, hip-hop, R&B, house music — they all go together because they all come from the same,” Brooks said, adding that he’s pleased to see the genre of house music evolve to include Afrobeats and other burgeoning genres.

He’s also hopeful that Drake’s new album will bring house music to a new generation and remind them that the genre has always been Black.

“The pandemic is what Drake is addressing with this album. It’s time to get up and move again. I’m so excited for young people to do that, to form that social connectedness again. That’s always been the purpose of house music.”