Drastic measure to stop massive 1859 New Bedford blaze haunted fire chief the rest of his life

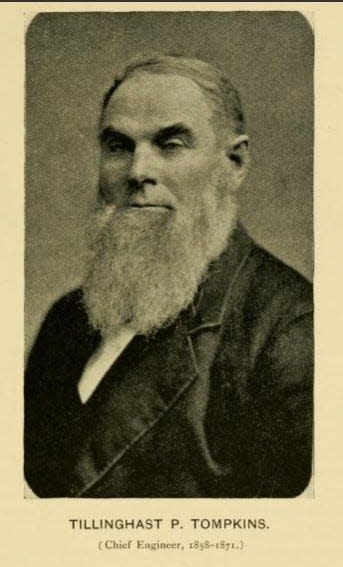

NEW BEDFORD — Drastic and heart-wrenching measures called into action to halt a massive fire sweeping through a section of the city and waterfront in 1859 left the city fire chief agonizing over those measures for the rest of his life.

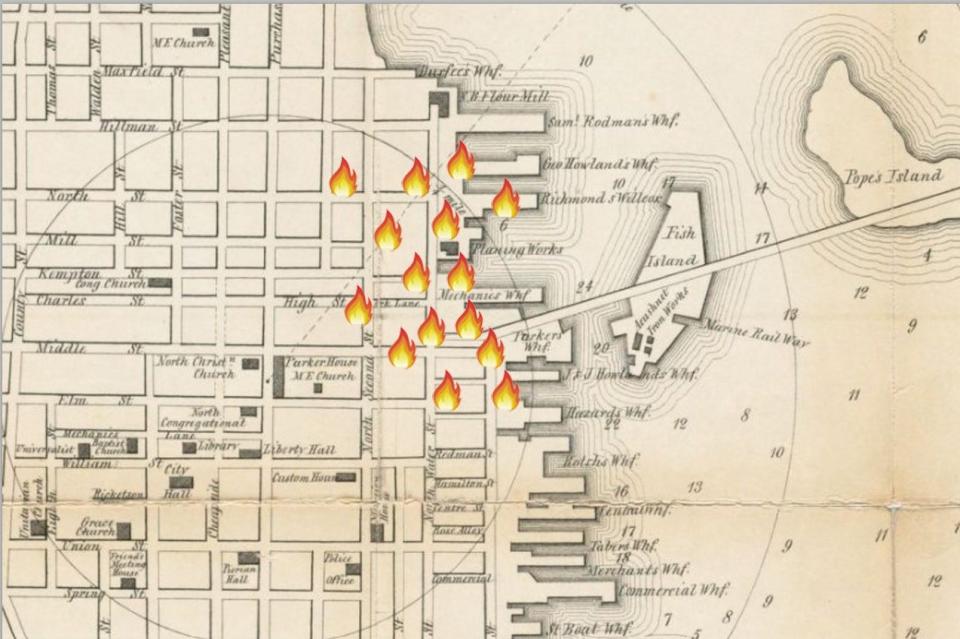

It was a fast-moving fire that had every intention of burning a section of the waterfront and North End to the ground.

It almost succeeded.

But Fire Chief Engineer Tillinghast P. Tompkins had an idea.

The 40-year-old Chief Tompkins ordered two buildings blown up on purpose to cut off the fuel feeding the flames being whisked north by a strong wind from the south. He hoped the move would give firefighters the edge in getting the main fire under control.

According to the “History of the Fire Department of the City of New Bedford, Massachusetts, 1772-1890" by Leonard Bolles Ellis, Chief Tompkins, was injured in one of the blasts. He was "struck on the head by a falling timber that cut a terrible gash through the scalp. It was feared for a time that the accident would prove fatal, but Mr. Tompkins soon recovered."

How and where the fire started

It was noontime, August 24, 1859, when Albert Sherman and William Hudson saw the fire coming from the Wilcox & Hathaway sawmill from their vantage point on the Fairhaven drawbridge. The fire, according to the Boston Evening Transcript, spread from the sawmill on Water Street to an adjacent lumber yard where there was “a great quantity of soft lumber.”

The newspaper indicated the blaze started when a downdraft in the sawmill’s chimney caused shavings inside to catch fire. “The watchman on duty barely had time to save himself,” the story said. He was the only one around as workers had left at noon for their dinner break.

A strong wind from the southeast shoved the fierce flames west, consuming businesses and homes on Water Street. It muscled northward, block by block, destroying more homes and businesses on North Street and Second Street. “Meanwhile, along the wharves the flames made steady progress, taking in their path all the buildings and their contents. Wilcox’s lumber yard was now one dense mass of flames, and the condition of things at this time was appalling,” Ellis wrote in his book.

Time is running out:Thinking about a summer rental in the SouthCoast?

Over 8,000 barrels of whale oil caught fire and exploded, spilling oil out into the harbor creating another path of flames on the water “forming literally a sea of fire,” Ellis wrote.

Whale ships that were tied to the dock were pushed out into the harbor to save them from the flames, however the ship John & Edward caught fire and flames shot up the masts and quickly engulfed the entire vessel.

The exploding of bomb lances (a type of whale gun), inside manufacturing buildings seized by the flames, sounded like artillery fire.

“The roofs of many of the houses in the northwest part of the city were several times on fire and most of the dwellings in that direction were only preserved by the constant watching of their occupants,” the Republican Standard newspaper reported.

Drastic measures taken to stop the fire

Fearing the flames could overtake the entire North End, Chief Tompkins ordered two buildings be blown up — creating a fire break — to keep the fire from advancing.

The first home to go was that of Dennis Daly on Second Street around 1:30 p.m. It was during the explosion of this home that Chief Tompkins sustained a gash to his head from a piece of timber shot out in the blast.

As the fire headed west taking out everything in its path, the destruction of Daly’s house stopped the flames from progressing to the south, the Republican Standard reported.

However, the fire’s northward path marched on, and consumed more houses and businesses.

The next home was blown up by the fire department at 2 p.m. and belonged to “widow Maxfield” who was married to the late Joseph Maxfield. The house was located at the corner of Second and North Streets. Her home, according to the Boston Evening Transcript, was “a very old one and once fired in the Revolutionary War.”

A combination of destroying the Maxfield home and the presence of a stone building owned by George & Matthew Howland kept the fire from spreading northwest.

What was 'Holy Acre'?: New Bedford neighborhood had a reputation — and possibly was haunted

The task to blow up the homes, as Ellis writes, was “quickly accomplished, and the stunning explosion that was heard in every part of the city was the announcement to the affrighted citizens that danger from that section was over.”

Whale oil, mostly from sperm whales and humpbacks, stored in barrels fed the flames, giving the fire the motivation it needed to keep moving. Thousands of barrels burned and exploded, but there were more barrels in the path waiting for the same fate.

A number of barrels were saved at the George & Matthew Howland building when they were "covered with seaweed and kept wet.”

The damage done

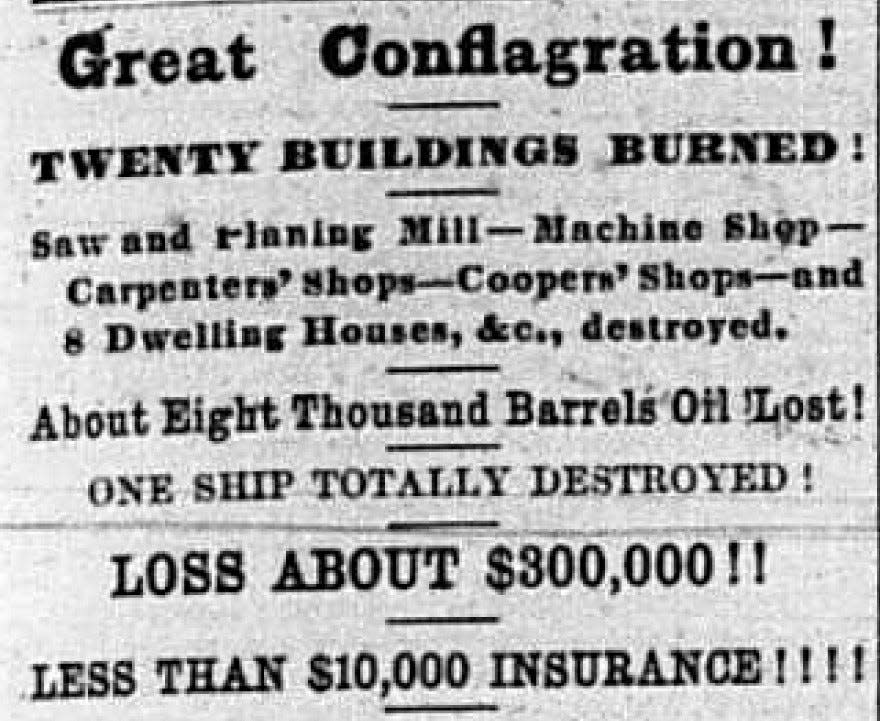

In all, over 20 buildings were reduced to charred remains by the monumental fire including the Wilcox sawmill, Thomas Booth's sash, door, and blind manufacturing, Warren Hathaway & Son's whaling apparatus manufacturing, Hayes & Co cask (barrel) makers, Gardner & Estes fish market, C&E’s Bierstadt’s turning mill, Edward M. Robinson’s oil yard, Pierce’s carpenter shop, as well as counting shops, paint shops, machine shops, rigging lofts, and numerous homes and sheds.

Many of the businesses had little to no insurance. According to the Republican Standard, “It may be considered very singular that there was so little insurance on the property destroyed. But the location was considered a dangerous one, and insurance companies demanded a very high rate” because they were considered "so combustible."

Remember the Schamonchi ferry?: Here's where it is now.

According to city records, the total amount of damage recorded came to $254,575, which equates to almost $9 million in 2022 dollars. Of the recorded amount in damages, only $6,579 was insured.

The fire was extinguished about 12 hours after it started.

“What made it especially sad was that the loss fell with such terrible force upon a class of our most industrious and worthy citizens, many of whom saw all the hard earnings of years in a few hours entirely obliterated,” Ellis writes.

No fatalities, several injuries reported

Chief Tompkins received injuries to his head and a broken shoulder when he ran toward the Daly house to “warn away two men who were near the building about to be blown up,” the Republican Standard reported.

David M. Barker, a blacksmith, suffered a broken arm.

The ill infant of Hattil Kelley was removed from their Ray Street home and died a few days later. This was likely Oliver F. Kelley (born to Hattil and Mary Kelley). He was 9 months old and is buried in Rural Cemetery. Newspaper accounts do not say whether the child’s illness was due to the fire.

A 2-year-old was found wandering around in his pajamas on Ray Street and wasn’t reunited with family members until several hours later.

The aftermath results in fire department changes

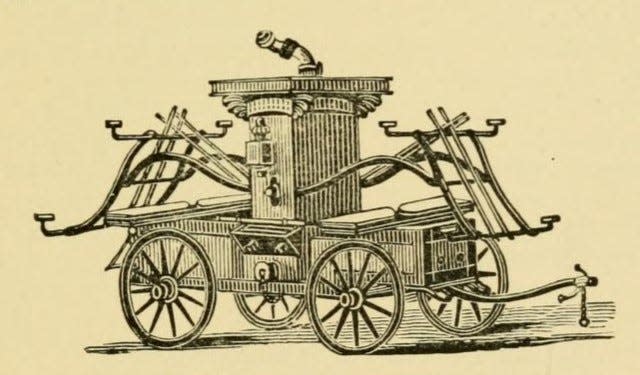

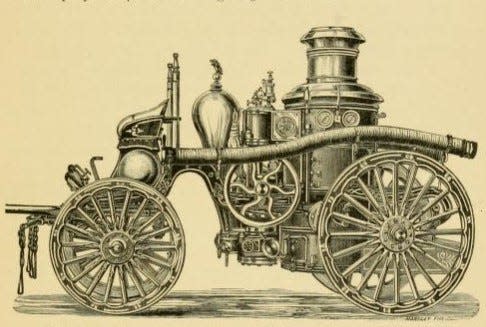

Soon after the devastating fire, residents began to call for changes in the fire department’s apparatus. They demanded replacing hand-pumping engines with the more modern steam-pumping engine. Both types were pulled by horses, but the mechanism to pump water onto fires changed from hand-pumping to steam-pumping.

It was only a few months after the 1859 fire, the city welcomed its first steam engine.

Chief Tompkins, who would retire from the fired department in 1871, was credited with bringing the department forward by changing over to steam-pumping engines.

"He still walks our streets, vigorous in mind, though scarcely capable of standing the fearful strain of an equal responsibility to the one of that dreadful day," Ellis wrote.

Download our app! Standard-Times digital producer Linda Roy can be reached at lroy@s-t.com Follow her on Twitter at @LindaRoy_SCT. Support local journalism by purchasing a digital or print subscription to The Standard-Times.

This article originally appeared on Standard-Times: This drastic measure was used to stop massive New Bedford fire in 1859