'I dread 2024': America's local election officials are being pushed to their limits

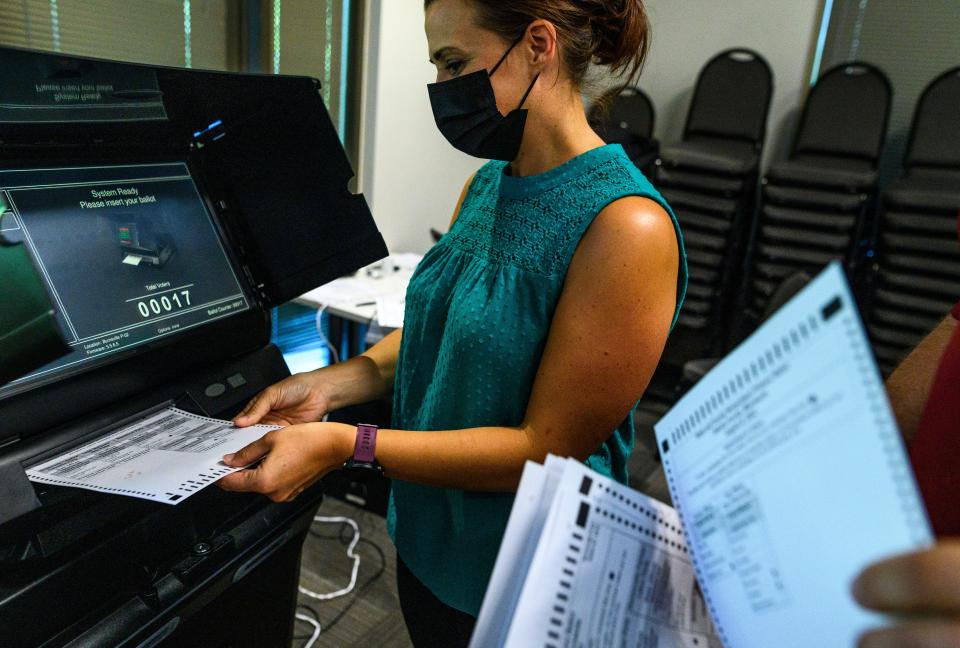

Lackluster funding, infinite work hours, staff shortages, limited resources, abusive phone calls and more: These problems are nothing new for America's election officials. They have stretched from long before the pandemic to today.

Despite it all, they have remained steadfast in the conviction that their job is what maintains American democracy. Failure is not an option.

“We don’t stop elections," said Karen Brinson Bell, executive director of North Carolina State’s Board of Elections. "We figure out how to proceed."

Now, however, their patience is being pushed to its limits by new hostility and threats – it's pushing officials away and it doesn’t bode well for future elections.

“I dread 2024, I don’t know how people are gonna be in 2024,” said Tonya Wichman, director of Ohio’s Defiance County Board of Elections. “You can only take so many phone calls that tell you how bad you are at your job.”

A recent report from the House Oversight Committee details the graphic threats and abuse election officials have had to endure. One social media threat called for an official to be hanged "when convicted for fraud and let his lifeless body hang in public until maggots drip out of his mouth," according to the report.

One in 5 election officials say they are “very” or “somewhat unlikely” to stay in their post through 2024, according to a March report from the Brennan Center for Justice. North Carolina has seen election directors change in 43 out of its 100 counties over the past three years, according to Brinson Bell.

The hostility just adds to the struggle for local elections officials who are in an intense and high stress job. They've had their grievances for a long time now.

It's always money

Election administration is heavily localized; their means of operation can vary wildly. Some counties have no problems with funding, while others feel squeezed.

In Missouri, St. Louis County’s Board of Elections was forced in 2019 to take out a $3 million loan to replace outdated voting equipment. Not buying the new voting equipment was not optional – voting technology has to be maintained and regularly updated to keep up with election security standards.

“We did ask our county council to fund that. They refused,” said Eric Fey, Democratic director of St. Louis County’s Board of Elections.

Fey and his colleagues had saved $4 million in recent years, expecting they would need new equipment. But the purchase ended up totaling $7 million.

St. Louis County is a larger county, with a population of nearly 1 million. In much smaller and rural counties, such as Williams County, Ohio, the funding problems are slightly different – there are only two full-time workers running the county's elections and serving more than 25,000 registered voters. The county can’t afford to hire anyone else full-time.

At Ohio's northwest border, next to Indiana and Michigan, AJ Nowaczyk is the deputy director of Williams County’s Board of Elections; he does pretty much everything.

“It’s just me and the director that run the show,” Nowacyzk said. “All the programming of the machines, the tests of the machines, the writing of the ballots, the keeping up with voter registrations, the public records requests. I mean everything. We’re the campaign finance department, too.”

It’s not like the bigger counties, where they have a staff for everything and overseeing operations. We are the operations.”

One of the largest challenges for Nowacyzk and his director is simply opening a door.

By law, both a Democratic and Republican election official have to be in the same room when preparing election machines. When Nowacyzk and his director are in that room, neither of them may leave without the other to do administrative work such as answering phone calls or fulfilling absentee requests.

Just two more full-time workers, Nowacyzk said, would allow them to at least “breathe” during an election cycle.

'It's a logistical nightmare'

On top of targeted harassment and death threats, election officials have to deal with the time-consuming tasks of fulfilling public records requests through the Freedom of Information Act.

Before 2020, public records requests presented no problem to election officials, taking up little time compared with today. Now, they are swarmed with requests that are often tedious and take them away from more important work.

Wichman said Ohio’s Defiance County Board of Elections received five public records requests with the same wording. The requests asks staff to “copy and scan every single piece of paper and ballot and anything that came up from the 2020 general election.”

Wichman and her team are federally mandated to fulfill those requests. She said they are working with their legal department to see if they can send back the requests and ask for a more narrow scope.

Most likely, they’ll have to hire a staffer dedicated to fulfilling those requests – which means valuable funding will go to new staff whose sole job is copying documents.

“It’s a logistical nightmare,” Wichman said.

The consequences for 2024 and future elections

Understaffed offices, mountains of public records requests and testing every button on every voting machine is a tiring endeavor for any election official.

“If you’re a truck driver, you’re supposed to stop after a certain number of hours of driving just for safety reasons,” Brinson Bell said. “No matter what the profession is, it makes you vulnerable to make mistakes, to be sick.”

“And then what do we do? If the people that are experienced and are professionals in this field are not able to keep going, who ensures that our elections take place?”

Some officials aren’t sure what can be done to make the job more enticing – beyond a pay raise.

“It’s a high-stress, high-pressure, no-margin-of-error kind of job. It’s pretty thankless,” said Aaron Ockerman, executive director of the Ohio Association of Election Officials. “And when you’re thrown threats of intimidation, lack of funding and all that kind of stuff in the equation, it’s a challenge. There’s no doubt about that.”

Ockerman, who's been in the industry for more than 20 years, said he sees young people come and go in the field due to burnout, and it’s discouraging to him.

For the next generation of election officials who do stay, they don’t yet possess the experience to run the elections that are so scrutinized today, Brinson Bell said. Normally, they’re taken under the tutelage of more experienced officials, but a lot of younger officials are now on their own.

“The institutional knowledge is really hard to replicate,” Brinson Bell said. “Our state law book’s about 3½ to 4 inches inches thick. There’s a lot to learn if you’ve not worked in elections.”

That leads to long hours. Ockerman remembered one young official who quit after working 80 hours a week with no days off.

The frequent election cycles, Brinson Bell said, makes it difficult to spend time with family.

Ohio’s most recent August primary elections took Wichman away from more of her daughter’s wedding celebrations than she had liked.

“Our plan was to take a week off, but I ended up only taking a day and a half,” she said.

Even then, she was still sending emails and making phone calls the day of the wedding.

Wichman shrugged it off.

“When there’s an election, it is what it is," she said.

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Local election officials face heavy turnover amid increasing threats