After a year of dread and violence, a Staunton suspect confesses, but is there evidence?

The brief warm spell in late December had come and gone, along with holiday celebrations and New Year’s parties. People didn’t stop going out on weekends, but Charles Culbertson had long noticed a pattern emerge about how they arrived and departed.

Buttoning up his coat against the cold as he left the Different Drummer he could see it clearly: women arrived in small groups to eat and drink and socialize. Once indoors, they might disperse to talk with different people.

But nobody left by themselves. In those weeks after the new year, he would have been surprised to see a lone female exiting a local bar and striding toward her apartment or dorm.

Things were different now.

The public had no idea that police were focusing on a single suspect and following his every move. It probably wouldn’t have mattered.

Once someone comes through the open window, the whole house never feels safe in the same way again.

*

The 1970s were drawing to a close; the best-of-the-decade lists were coming out. As people tidied up after the holiday, a TV commercial advised you to “bag up your troubles” in trash bags and smile, smile, smile.

In Staunton, though, things were coming loose again.

Christmas came for James Bruce Robinson, even if it was a day late, and he was back on the streets.

The stocking mask rapist was in a jail cell for four days, but on Dec. 26, 1979, after being convicted of trespassing, he was released while awaiting trial for the peeping tom charge.

On the night he’d been arrested, Robinson had denied having anything to do with the rapes and had agreed to take a polygraph test.

After he was released, Special Agent Darrel Stilwell of the Virginia State Police wasted no time in sending out Patrolman L.M. Kerr and Sgt. Ronnie Whisman to arrange the details. They went to Robinson’s apartment that evening at 7 p.m. to get his consent to pick him up the next morning and drive him down to Salem for the polygraph.

Robinson balked. He said he had a phone call to make and asked them if they could come back later to talk.

Two hours later they returned and were greeted by Robinson and his girlfriend. Now Robinson was reluctant to take a polygraph. The two agreed to go for a ride with the police and discuss it. They stopped in a lot on North New Street to talk.

“During this conversation,” Kerr noted in his report, “he would agree to take the examination, while his girlfriend would not. Then she would tell him to take the test, and he stated that he wouldn’t do so.”

Robinson’s girlfriend suddenly said, “Why should he go? There haven’t been any more rapes.”

“That’s right,” Robinson said quickly. “There haven’t been any more rapes. They have stopped.”

Robinson said he wanted more time to think about it, and the police drove the couple back to the Woodward apartment building.

The next day, police approached Robinson again about a polygraph, after he spoke to his attorney. He was adamant now that he was not going to take one.

*

As the task force conducted interviews focused on Robinson, a portrait began to emerge.

Sgt. Lacy King spoke with two members of the state parole and probation office. King wrote in his report that a cousin of Robinson’s told one of them "that James Robinson liked to smoke marijuana and go in to houses at night.”

His most recent convictions were of breaking into two houses in Salem, “and in both cases the residences were occupied by women,” King wrote. “This subject has lived in several cities in this state and it appears that each time, he has had some trouble with the law and in the respect that it has to do with going into other people’s houses.”

Joe Andrew Edwards, a security guard, was one of the initial subjects that police investigated.

He was also Robinson’s brother-in-law, and the Staunton connection. After Robinson was released from prison on March 5, he spent “about a week” with his mother in Millboro; then Edwards, who lived in the Woodward apartment building, “brought him to Staunton where he began looking for a job.”

Edwards told police that he’d noticed his brother-in-law bringing things into the apartment that he said people had given him. It seemed odd to him; he didn’t consider Jimmy to be a thief but it didn’t make sense that he’d have the money for some of the stereo equipment that he was obtaining, or that he’d be so interested in buying some of the other smaller items, like an alarm clock.

New search warrants issued in mid-January helped recover items overlooked in a first search of Robinson’s apartment, tying him to break-ins in May and July.

On Jan. 15, police charged Robinson with four break-ins and burglaries based on evidence found during those searches.

Confronted with the additional charges, Robinson “maintained his innocence for a good while,” Stilwell wrote. When police explained they had gathered evidence from his apartment of items stolen from the four homes, he eventually admitted to three of the break-ins and larcenies. He said he’d bought stolen stereo speakers found in his apartment from a man named Spooney.

Then he came out and admitted to an additional break-in on Aug. 1 where he stole nude pictures he found in an apartment on East Beverley Street. He also said he was the person who’d been seen using a ladder to climb toward a second-floor window of a North Market Street home Nov. 22.

“I put the ladder up to the roof and climbed part of the way up the ladder,” Robinson said in a signed statement about that night. “I saw two girls looking at me and climbed down and ran. I don’t know what I climbed up on the ladder for. I was high and didn’t really know what I was going to do.”

Stilwell suddenly had two things going in his favor. First, the ladder connection. He had Robinson’s prints at a rape crime scene where a ladder was used to gain entrance; and he had Robinson admitting to using a ladder at another address.

Second, he had a suspect who was willing to widen the conversation of his illegal activity. He pressed Robinson on the North New Street break-in.

Robinson seemed to have a very good memory of the home except for the bedroom, even though he’d stolen a garnet ring from that room. He was soft-spoken in general, wrote Stilwell, except when the rapes and the theft of women’s undergarments were brought up.

When the other rapes were brought up, Robinson had a ready excuse for any evidence of his presence. It seemed he was always looking to buy marijuana, and he’d do that by going out at night to a house where a seller, always a man, was supposed to live, and looking through the windows to make sure he was home. The night in December he was arrested, he’d made a similar claim, though he had no money in his pockets to make the buy.

He said he was familiar with the house on West Frederick Street, site of the attempted rape in late May, because he was “pretty sure that was the house he used to go buy reefer from a light-skinned black guy but denied he had ever attempted an assault on anyone in the building.”

He added that in one case he had helped a woman move from a house on Kalorama Street, so that would explain if his prints were found at that location.

“It was obvious when talking to Robinson that he was intentionally trying to explain away any possibility that he perpetrated any of the sexual assaults or attempted assaults,” Stilwell wrote. He could describe in detail some of the homes but “shunned the areas of all the assaults and crossed himself up in his statements to the point there was not much doubt he had perpetrated all of the assaults.”

One thing he couldn’t quite explain was the palm print on the banister below the window appearing two months after his break-in, found when police were investigating the July rape. Robinson argued the print was from his April burglary. For some reason he couldn’t explain, he said he’d decided to try the window from the inside, even though it was eight feet above the stairs and would not be a safe escape route. He claimed he got a chair from the kitchen, placed it on the stairway, and stood on it to reach the window.

The opening Stilwell needed to close the case was right in front of him in his mind’s eye: that open window. Why would Robinson care about the window if he had no plans to come back?

Things were starting to come into focus. But like when you look through binoculars at a distant object and instead see two objects, they weren’t fully aligned yet. Stilwell was sure he had his sights set on the right person; he just needed to make the proper adjustments to get clarity.

Robinson’s arrival in Staunton lined up with the initial attempted sexual assault of two underage students by a stocking-masked man at Stuart Hall on March 10, the rape of a Mary Baldwin student on March 14, and the string of sexually-oriented break-ins and rapes that had plagued the city until his arrest just before Christmas.

Now James Bruce Robinson was back in jail.

Stilwell and the task force were sure they had found the nightmare that had been stalking the city. With more knowledge of Robinson, his criminal past and his behavior, Stilwell thought it was time to turn up the heat.

“Robinson is quiet. He listens well,” he wrote in his report. He also clearly liked to talk. Stilwell hoped that would be his undoing.

*

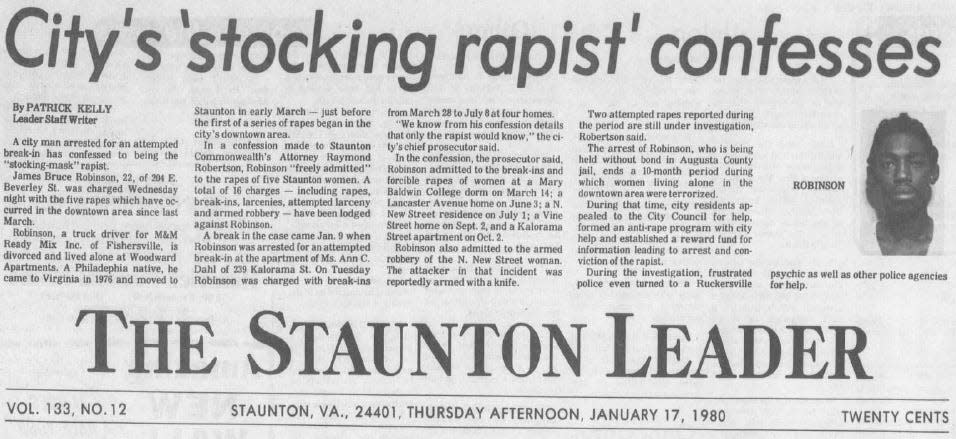

Robinson faced a Jan. 16, 1980, hearing for the April break-in of 230 Kalorama St. Before he went to court, he and his attorney, William Bobbitt Jr., met with Commonwealth’s Attorney Ray Robertson. With Stilwell and other members of the task force present, Robertson advised the public defender of the new charges Robinson had admitted to the day before.

He also advised that there was evidence to charge him with the July rape. Robertson asserted that “there were enough facts available to cause the belief that James Bruce Robinson was the stocking mask rapist, and that if he was and would clear up all the cases, he would recommend a 20-year sentence on all charges with none suspended.”

After the hearing, Bobbitt authorized the police to talk with his client and said that he would not need to be present. An unusual allowance, many defense lawyers would agree.

Police brought him back to the station and provided him lunch. Despite his denials, Robinson seemed to want to be cooperative, and Stilwell tried to bring him out more.

“We’d go over the types of offenses that we thought he’d probably committed.” Anything to keep him talking.

Robinson began owning up to the rapes, but as in the previous conversation he could not bring himself to talk in detail about them, though he could describe the victims, the furniture in the rooms, the pictures hanging on the walls.

Stilwell wrote that Robinson eventually characterized the crimes as if “some unknown part of him may have caused him to commit the rapes and then it was blotted out of his memory.” Robinson said that he did not know any of the victims and was sorry for what he’d done.

Stilwell remembers at one point in the conversations Robinson said something striking. “He said he felt like he needed help.” Stilwell understood the stakes. As soft-spoken and intelligent as he was, Robinson was admitting to rapes in which he held women down at knifepoint, sometimes cutting them. He made attempts to cover the faces of some of the women, a dehumanizing behavior. When would the implied violence and de-personalization of the victim turn to life-taking violence? He felt Robinson was reaching a similar conclusion.

The special agent also knew a confession doesn’t make a case airtight.

They needed more details. In a case with scant physical evidence, before the days of DNA, they needed to be sure he was the person who committed the rapes.

The next day, the detectives took Robinson for a sightseeing tour of the city the stocking mask rapist had terrorized for 10 months.

Staunton’s a city of hills; you can’t drive for a minute without finding yourself on one, and it always seems you’re traveling up a hill more often than down. In winter the trees that adorn the yards seem to withdraw, and the old houses seem more prominent. Driving up hilly North New Street on a cold gray day, it might seem the houses are crowding together in a group, as if to overhear the conversation of people in their cars.

“I remember this as if it were yesterday,” Stilwell said. “I’d say, ‘We’re in the area where one of these assaults occurred. Now when you see the house that it occurred in, you tell me to stop.

“And he did. He would sit there and tell us exactly how he went into the house, and everything about it.” How’d he enter the building? Where'd he find that ladder, anyway? And after you left, where did you leave it?

They sat in the car and he talked over the heater’s hoarse roar. Those details would be brought up at Robertson’s trial.

*

For once, the news was reported on time.

When she saw The Leader story that James Bruce Robinson had been arrested and confessed, the July victim thought to herself, “Thank goodness.” A similar sentiment was likely being thought and spoken by many of the city's women. Maybe this time, the nightmare really was over.

*

James Bruce Robinson had his day in court. It was a brief one.

Surviving records in circuit court show a plea agreement had been reached. Robinson appeared in court Feb. 6 and acknowledged guilt in five rapes and more than a dozen other felonies, including 11 breaking-and-entering felony charges, four charges of felony grand larceny and one charge of felony robbery.

He was not charged in the attempted rape of two Stuart Hall students, nor in the May rape attempt by a stocking-masked man at a Frederick Street home. He was not charged in the attempted rape in November.

He pleaded guilty to the rape for which Theodore Gray was indicted by a grand jury, and for the rape in which Gordon Smith was initially identified and jailed. Smith remained incarcerated in a mental institution at the time, though no longer in a ward for criminal patients. Gray had been released in November after the commonwealth’s attorney decided not to prosecute.

No transcript of the trial exists in circuit court records. A court document dealing with the indictments and plea bargain, and the judge’s sentencing decision, are all that remain of the proceeding.

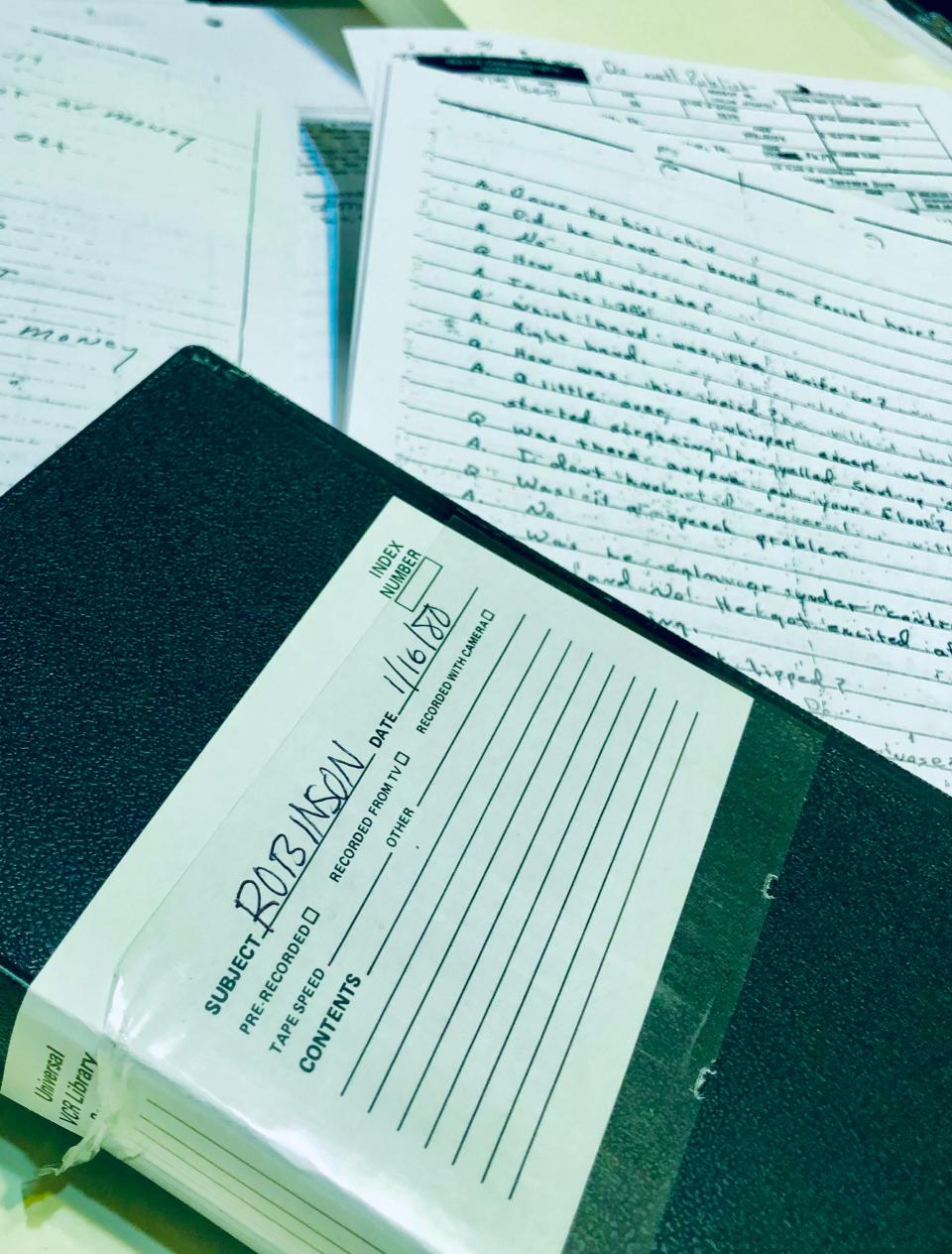

The trial was recorded on three cassettes but not transcribed. When The News Leader examined the cassettes in the office of the clerk of circuit court in 2019, it was discovered that the tapes were broken away from their leader tape and spool.

Then-circuit court clerk Tom Roberts refused to repair the cassettes, or to let them be taken out of the building for repair by a third party paid for by The News Leader.

Special Agent Stilwell was listed as the only witness. He recalled that in a trial involving a confession he would have read the victim’s statements and the defendant’s confession to the judge. None of those materials are among the printed documents available at the courthouse.

He would then have explained how the information that the defendant provided in conversations with detectives included details that only the rapist could know about all five attacks. No transcript of this statement exists at the courthouse.

The sentencing guidelines for rape in Virginia in 1979 indicated imprisonment of five years to life. Robinson held a knife to his victim’s throats as he raped them. He threatened to kill them. The additional violence and trauma on the victims is not part of the surviving trial record, which states only the 21 charges to which James Bruce Robinson was pleading guilty.

The judge sentenced Robinson to 20 years on each count. “And it is further ordered that the penitentiary sentences this day imposed shall run concurrently.” Translation: 20 years, not 400.

Or in layman’s terms, four years per violent rape.

— Jeff Schwaner is a journalist at The News Leader in Staunton and a regional storytelling and watchdog coach in USA TODAY Network-Southeast. Contact him at jschwaner@newsleader.com.

NEXT UP IN 'THE STOCKING MASK'

A Black man who was arrested and imprisoned as the "Stocking Mask Rapist" of Staunton would finally be released from incarceration.

The Virginia General Assembly decided to pay him $5,000 to make up for the loss of his livelihood while in jail. In those months he’d lost more than a livelihood, though; he’d lost friendships and the trust of others.

A rape survivor had identified him from a photo lineup and also claimed to recognize his voice. For complicated reasons, he had flunked a polygraph test.

He said a retired judge later told him the woman had been coached to identify him.

Ask him today, in the 2020s, what has changed?

“It’s more systematic now than it was back then,” Gray said of the racism in American law enforcement. “But to me it’s still the same."

PART 1: Serial rapist stalks vulnerable city while Staunton police, women’s college stay silent

PART 3: Cops admit predator is at large. Staunton women told to use ‘can of hair spray’ for defense.

PART 4: ‘Everyone’s scared to walk outside their houses — or stay in them’

PART 6: ‘You got two innocent people in jail, and a rapist still out there’

PART 7: Women make demands. A psychic makes predictions. And a Virginia city holds its breath.

PART 8: Things go ‘round and round’: Two unlikely sources help police close in on Staunton predator

PART 9: After a year of dread and violence, a Staunton suspect confesses, but is there evidence?

This article originally appeared on Staunton News Leader: Staunton stocking mask rapist confesses, but is there enough evidence?