'He dreams of killing others': Witnesses say Nikolas Cruz's childhood marked by paranoia, aggression

FORT LAUDERDALE — In a neighborhood in Parkland, two children played outside. You wouldn’t have guessed that the one with auburn hair was the older of the two. He was smaller than his younger brother, and less coordinated. Less confident.

A neighbor called them over to her mailbox and introduced them to Steve Schusler, who in 2009 had just moved in across the street.

“This is Niki, and this is Zach,” she said, and pointed. “Niki’s the weird one.”

The prosecutor: Meet the 80-year-old prosecutor making the case for Nikolas Cruz receiving the death penalty

Anything but 'normal': Lives of Parkland victims' families marked by absence, anguish, sorrow

6 minutes of terror: New revelations rise as Parkland survivors recount Nikolas Cruz attack

Nikolas Cruz scrunched up his face. The comment hit him like salt on a snail, Schusler said. He seemed to shrivel inward. Schusler was stunned that she’d said it at all.

But it was true, he added. There was something off about the eldest Cruz brother. His ears were too big for his head, and his head too big for his body. He wouldn’t look a person in the eye and seemed to shirk away from any contact.

“He did not have the boyhood image,” Schusler told jurors Wednesday. “You could look at him and you can see: Something’s not right.”

Unlike the 10-year-old who wilted at the insult, Cruz, now 23, listened expressionlessly as witness after witness described the peculiar and troubled child he’d been. His own team of public defenders called them to testify in the Fort Lauderdale courtroom this week. It might be their only shot at saving his life.

Jurors in the case will recommend whether Cruz, who pleaded guilty to killing 17 people and wounding 17 others on Feb. 14, 2018, receive the death penalty or life in prison without parole. A recommendation of death must be unanimous for Circuit Judge Elizabeth Scherer to pass the sentence.

Anger issues surfaced early after birth to drug-addicted mother

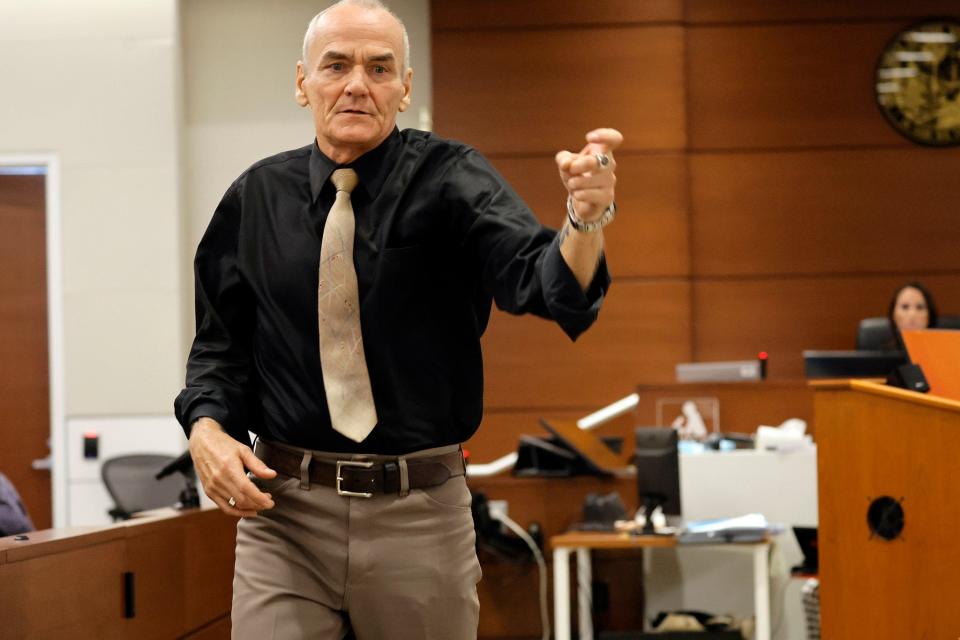

Cruz's attorneys have called upon people with intimate knowledge of the gunman's upbringing to persuade them that his path to killing 17 people at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School was set long before the day of the massacre.

“He was poisoned in the womb," lead public defender Melisa McNeill told the jury Monday. "Because of that, his brain was irretrievably broken, through no fault of his own."

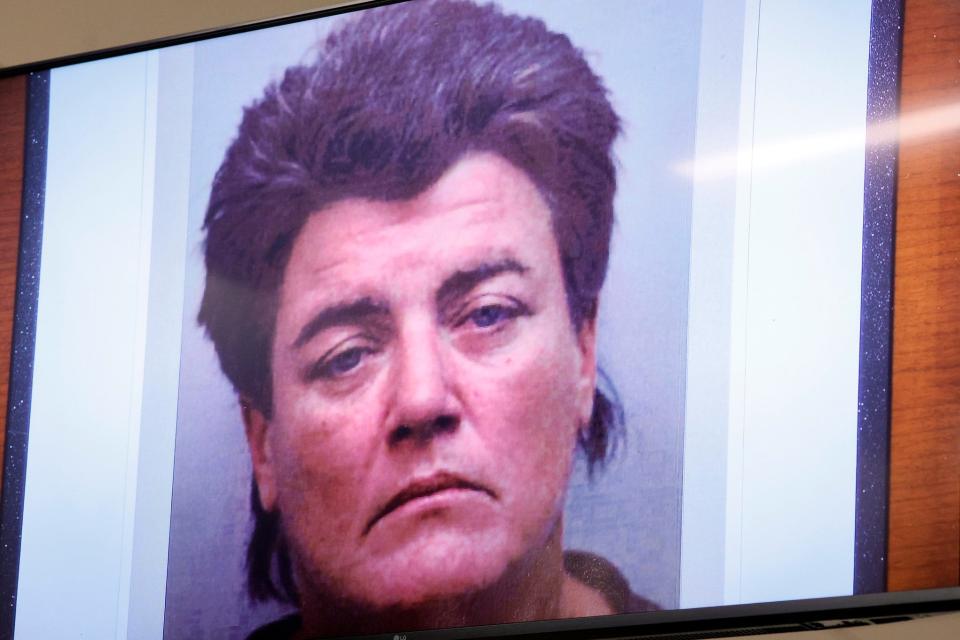

Lynda Cruz, his late adoptive mother, doted on Cruz when he was born in 1998. She didn't know that his biological mother, Brenda Woodard, walked around Broward County sipping a Big Gulp cup filled with malt liquor, or that she smoked cigarettes and snorted cocaine while pregnant with him.

Even at 1 year old, Cruz was different from other children, said Anne Marie Fischer, the former director of Young Minds Learning Center in Broward County. He looked and acted different, rocking back and forth in his high chair and avoiding eye contact. He seemed overwhelmed, Fischer said.

By 4 years old, he'd scale furniture and pace his preschool classroom to avoid other children, curling his hands into paws and hissing when they came near. If he saw one with a toy he wanted, he'd walk up and smack it out of the other child's hand, or bite them.

Children in the neighborhood sometimes teased him for peeing his pants, said Trish Devaney Westerlind, a family friend, and he'd break their toys because of it. He never got over things quickly.

She saw that he was different, falling behind even his younger brother on milestones like talking and standing upright. By elementary school, Cruz seemed to know there was something wrong, too.

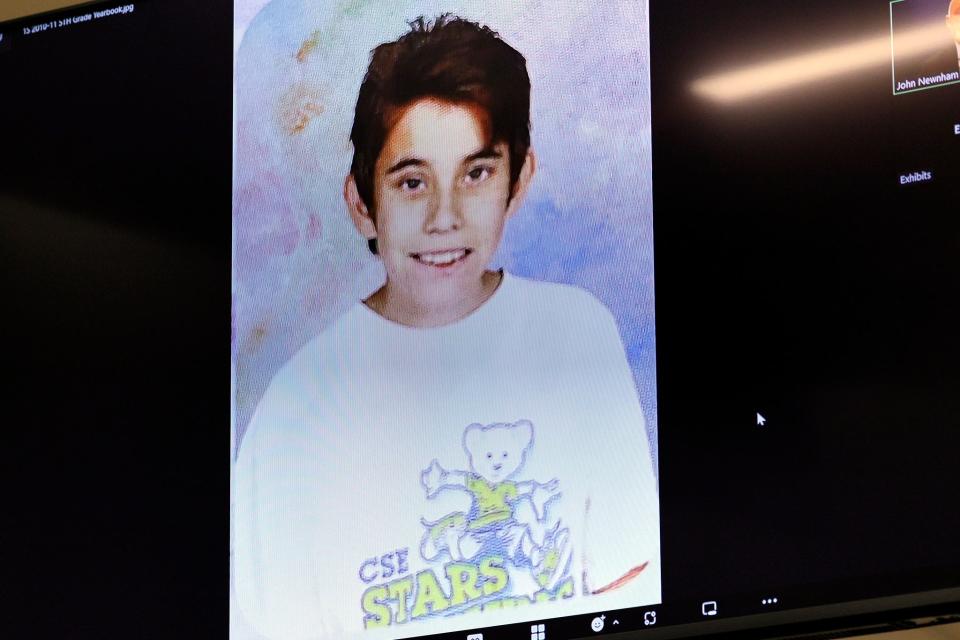

" 'I'm just stupid,' " Cruz sometimes told John Newnham, a former counselor for Broward County Public Schools, who testified Tuesday. " 'I'm a freak.' "

Adoptive mother protective, overwhelmed, resisted counselor's advice

Elementary-aged Cruz was a perfectionist, Newnham said. He'd erase and re-write, and erase and re-write some more until he'd broken his pencil or crumpled his worksheet.

Cruz told Newnham that he felt different from his peers, as though he were somehow "less than," and they judged him for it. His mother took longer to come to terms with it herself.

"She didn't want to see anything wrong with him," Westerlind testified.

Lynda Cruz was overwhelmed, Newnham said. Her husband died when Cruz was 4, leaving her to raise two defiant and temperamental young boys. She was reluctant to discipline them because she was "somewhat fearful of them," the counselor said.

He remembers making the same recommendations to her as the year went on: respite care, in-home therapy, parenting classes. She didn't follow through on any of them, he said.

By third grade, Cruz's anxious behavior had become destructive. He'd trashed his desk at school and cursed at his third-grade teacher, threatening to stab her. He hit a classmate with a lunchbox and once threw his textbook into the swimming pool when he didn't want to do his math homework.

"Cursing, screaming and yelling a lot," said Laurie Karpf, a psychiatrist who treated Cruz from age 10 to 13. "Repeating himself."

Specialist after specialist described to jurors an anxious and aggressive child who was slow to meet his peers' gazes and quick to throw a tantrum. Lynda Cruz told each one that he was adopted, but none knew the scope of his birth mother's addiction or its potential impact on Cruz. They medicated him for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

His mother wanted to do right by him, they said — that was clear to them all. But she didn't always know how, moving from one doctor to the next when her insurance changed, and at one point stopping his ADHD medication altogether when it appeared that it wasn't curbing his aggression. His behavior only worsened.

School counselor reported hearing Cruz speak of violent dreams

By 2014, four years before the Parkland shooting, Cruz began to dream of death.

"Per recent information shared in school, he dreams of killing others and is covered in blood," wrote a therapist at Cross Creek, a Broward County public school for students with emotional behavioral disabilities.

"He seems to be paranoid and places the blame on others for his behavioral problems," the letter continued. "He has a preoccupation with guns and the military and perseverates on this topic inappropriately."

The therapist wrote that Cruz destroyed his television after losing a video game, carved holes in the walls of the bathroom and used sharp tools to cut through furniture upholstery.

He "has a hatchet that he uses to chop up a dead tree in the backyard. Mom has not been able to locate that hatchet as of lately."

The therapist finished the letter by recommending Cruz's psychiatrist at the time, Brett Negin, reassess his response to his medication, as she viewed it to be "limited at best." Negin told jurors he never received the letter.

Around this time, and from his home across from the Cruz family, the neighbor kept a watchful eye. Schusler said he'd grown wary of the now-teenaged Cruz.

He'd seen him running outside of his home, firing an airsoft gun "spasmodically." The way he ran was lurching and flailing, like a 2-year-old who couldn't yet walk, the neighbor said. It was disconcerting.

Schusler would wave at the brothers as they walked to school and watch Cruz duck away, shriveling into himself as he had when their neighbor insulted him. He often saw Cruz standing apart from his brother and his brother's friends as they rode skateboards in the driveway.

Schusler gawked then when he saw Cruz's face on the television eight years later, pleading guilty to murder and attempted murder. During his plea, Cruz appeared to blame "marijuana and drugs" for violence, and Schusler began to search the internet for the phone number of the gunman's attorney.

"I said, 'Wait a minute. You need some information here, ' " Schusler said. "This boy did not 'go bad.' He was never right."

He glanced at Cruz in the courtroom and said he felt bad to say the words in front of him. It was like he had stooped to the level of the neighbor who called the 10-year-old boy weird all those years before, he said, and he'd found that "disgusting."

Cruz didn't look as though he heard him at all.

Hannah Phillips is a journalist covering public safety and criminal justice at The Palm Beach Post. You can reach her at hphillips@pbpost.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Beach Post: Witnesses say Parkland gunman Nikolas Cruz paranoid, aggressive as child