The drive behind Germany's pro-Israel political consensus

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

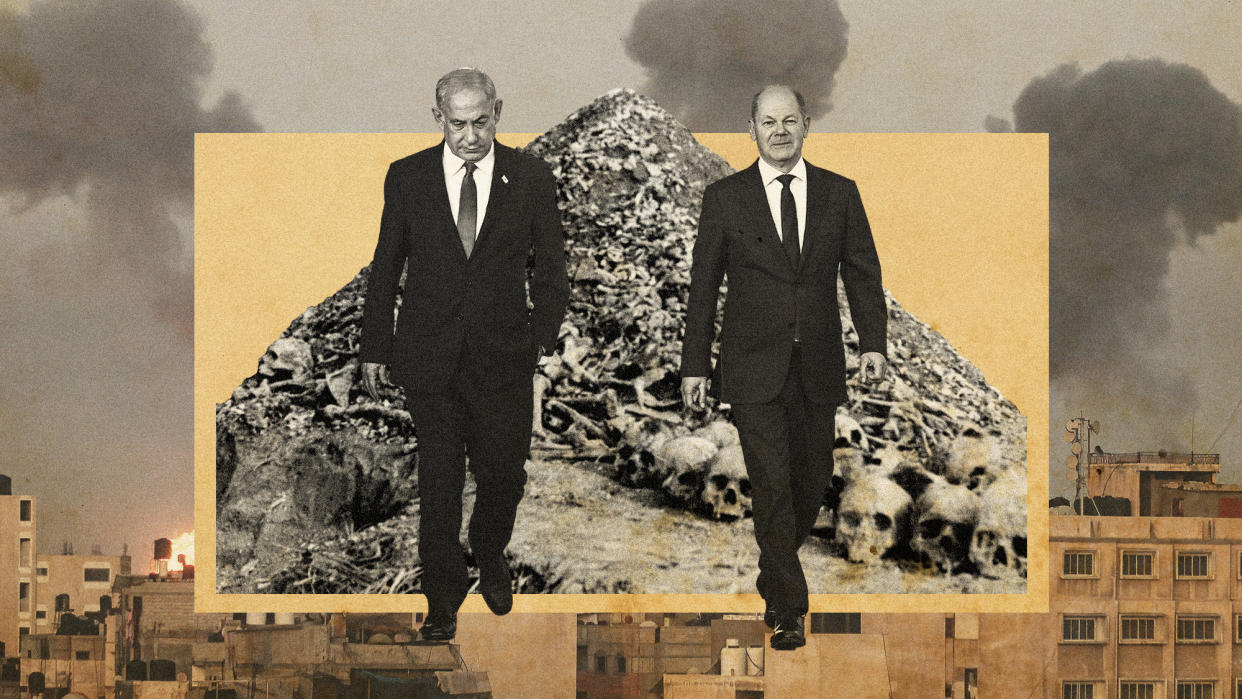

The relationship between Germany and Israel carries a unique historic and symbolic significance.

Berlin's political leaders declare Israel's security to be a "raison d'etre for the German republic", said Politico. They even have a word for it: "Staatsräson".

On a trip to Israel shortly after the 7 October Hamas attacks, the German chancellor Olaf Scholz made it clear. "German history and our responsibility arising from the Holocaust make it our duty to stand up for the existence and security of the State of Israel."

A 'special relationship'

The notion of a "special relationship" with Israel took hold in Germany in the 1970s. In recent years it has received "near-universal approval among Germany's political class", said Leandros Fischer in the Journal of Palestine Studies in 2019.

Parties from across the political spectrum have in effect "endorsed the consensus on Israel", he said, banning, for example, any discussion of the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement.

This relationship is driven by the "special responsibility" Germany feels it has to "the Jewish people, to Israel and to combatting anti-Semitism because it was responsible for the Holocaust", said Al Jazeera.

This is reflected not only in the country's strict criminal codes used to prevent the glorification of Nazi Germany, Holocaust denial and antisemitic hate speech, but in the rhetoric of its political leaders.

"We are in Germany, the country that practically annihilated Judaism in Europe," Karin Prien, a politician from the centre-right Christian Democratic Union (CDU), told The Guardian. "Eighty years on from the liberation of Auschwitz, we still bear a special responsibility to stand up against antisemitism."

Free speech fissures

The 7 October Hamas attacks prompted a surge in both Islamophobia and antisemitism in Germany, mirroring a pattern seen across much of the Western world. According to RIAS, Germany's Department for Research and Information on Antisemitism, reports of antisemitic threats increased by more than 300% in the month following the attack, said DW.

The response from the German state was to impose an "intense clampdown on freedom of expression" that included a ban on pro-Palestinian rallies and attacks on artists and academics by German politicians, said +972 Magazine, which describes itself as an independent, non-profit magazine run by Palestinian and Israeli journalists.

Speaking to The New Yorker, the artist Candice Breitz, who had her government funding pulled, said German politicians see it "as extremely risky to be connected with an event that had Palestinian speakers".

In November a draft law was submitted to the German parliament that tied German citizenship to a formal commitment to "Israel's right to exist". A month later, the state of Saxony-Anhalt passed its own decree requiring those applying for German citizenship to recognise the State of Israel.

The German political elite has "justified its stance with the alleged feeling of guilt for the Holocaust and the need to make amends by supporting Israel", said Denijal Jegic on Al Jazeera. Yet under this "cover of 'acting morally'", it has sought to "further normalise anti-Arab and anti-Muslim racism, justify more draconian anti-immigration policies, and downplay the persisting anti-Semitism among white Germans".

Cult of guilt

Some argue Germany's leaders are merely reflecting the position of their public, with polls showing support for Israel being higher among people in Germany than in many other European countries.

At the same time, debate around the role that shame plays in Germany's foreign policy – especially in relation to Israel – has been intensified by the war in Gaza.

On a trip to Berlin last year, Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan claimed that Germany was too absorbed by historical remorse to grasp the reality of the Middle East. It is a sentiment reflected by the far-right party AfD (Alternative for Deutschland), which has surged in the polls aided in part by its rejection of Germany's culture of remembrance "as a mere Schuldkult (cult of guilt)", said Joerg Lau in The Guardian.

"The idea that Germany suffers from an overdose of Vergangenheitsbewältigung – the German term for dealing with the Nazi past – is not new," he said. But to believe the German political establishment is "captive to an oppressive mindset that limits its ability to speak out against Israel" is "a dangerous conspiracy theory that needs to be debunked".