Drive-through drama: Shia LaBeouf, on-set chaos and an L.A. play about COVID

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

First things first: There will be no group photo tonight.

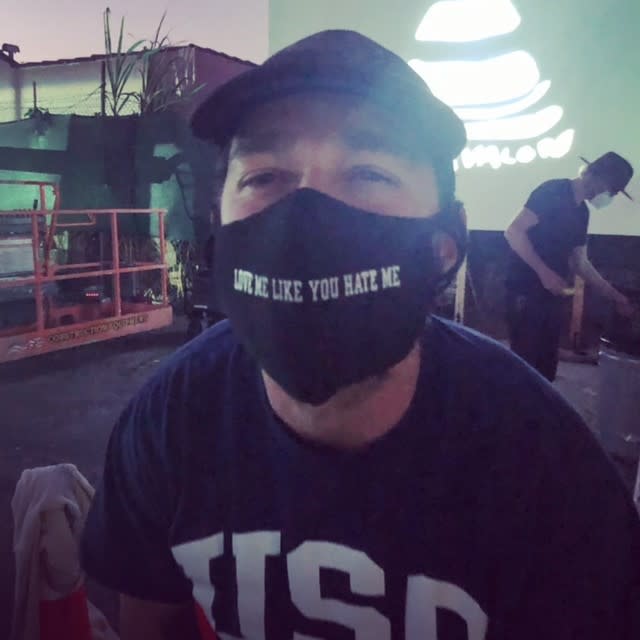

“F— that, it’s cheesy!” bellows Shia LaBeouf during rehearsals of “5711 Avalon,” a new play from his Slauson Rec. Theater Company. The group photo, for this article, was to feature LaBeouf with company co-founders Bobby Soto and Donte Johnson along with others. But LaBeouf will not have it.

“Not doin' it!” he yells, before stomping off.

Maybe it’s the glowing full moon, bathing this South Los Angeles parking lot staged to look like a drive-through COVID-19 testing center, the setting for the play; maybe it’s the stress of an all-too-real pandemic; or maybe it’s just LaBeouf. But chaos reigns supreme on the set of “5711 Avalon,” which opens Friday.

The free 45-minute play — which audience members will watch from inside their parked cars, with audio coming from the radio, as if at a drive-in movie — documents a day in the life of a testing center. We don’t know much more than that early on because LaBeouf misses a scheduled phone interview the day of rehearsal and cancels a promised makeup interview afterward.

The environment at rehearsal compounds the confusion. Production assistants, writers, actors, directors — it’s often unclear who is who and many are hyphenates — scurry around the set as cars that are part of the play stream through the lot. It’s dark and the audio on the exterior speakers is at times clear, at times staticky or screeching. Disparate images flash across video screens placed around the lot — healthcare workers suit up in PPE on one, a belligerent blond picking a fight with a test center volunteer on another.

Some answers emerge, eventually: The play has an immersive, theater-in-the-round element. With about 20 audience cars in attendance, the action takes place in the middle of the lot as well as along the periphery. As cars pass through, dramas ensue simultaneously across the unconventional stage. The mostly quotidian events are based on interviews that the theater company conducted with real front-line workers and people being tested, as well as news reports from April to June. One COVID test seeker refuses to wear a mask, for example, and one woman’s anxiety flares at the prospect of being tested.

The on-screen imagery we’re seeing is live footage from cameras mounted inside the cars as well as on-the-ground coverage shot by a character in the play who, as part of the narrative, is there to document events. The shaky video footage lends an urgent cinéma vérité aspect to the production.

With all the concurrent action, however, it’s unclear what’s part of the play and what isn’t. A blaring car horn goes off (not part of the play). A Ford sedan speeds into the lot, dangerously fast (part of the play). The video blinks off (not part of the play, infuriating LaBeouf).

“I want Leo live! Now!” LaBeouf commands, kicking a random piece of plastic across the asphalt.

LaBeouf is watching the action intently from the sidelines, gripping a plastic coffee cup and darting among vantage points, often yelling mid-stride. “It’s not realistic, it’s not real!” he shrieks, standing by a tech rehearsal tent facing center stage. “Come on! It’s not working!” he yells moments later, now perched on the giant wheel of an orange construction vehicle. He jumps to his feet: “No-no-no-no-no!”

To some, his bad behavior isn’t entirely surprising. LaBeouf, who wrote and stars in the 2019 film “Honey Boy,” based on his dysfunctional relationship with his father and written after a stint in rehab, is known to be a performance art provocateur and all-around troublemaker who’s had high-profile run-ins with the law. In 2014 he was arrested for drunkenly disrupting a Broadway performance of “Cabaret,” and last month he was charged with battery and theft after a June dust-up in which he was accused of stealing another man’s hat.

Among his performance art antics: He donned a brown paper bag over his head bearing the words “I am not famous anymore” on the red carpet of the 2014 Cannes Film Festival. Shortly after, he staged an interactive art installation at L.A.’s Cohen Gallery titled "#IAMSORRY” in which he sat silently with visitors while wearing a paper bag with the same message on his head.

The frenetic nature of the play itself makes sense, says Charles Whitcher, one of the play’s directors. “It’s set in the early days of the pandemic when everyone was so stressed, tensions were high and everything was so unknown,” he says. “The presentation, there’s a little chaos, but it’s conveying the moment.”

LaBeouf founded the theater company, which is based in South L.A., in 2018 with actors Soto and Johnson. They met on the set of director David Ayer’s “The Tax Collector,” which starred Soto and LaBeouf and featured Johnson in a small role. The idea was to create an unconventional and experimental theater company that develops original material through improvisation and collaborative work. Everyone in the company is credited with writing “5711 Avalon,” a process that took place over several months on Zoom calls. Several of the calls were live streamed on YouTube and viewable by the public. Four people are directing.

The nonprofit company, which has about 45 members, is also encouraging new actors and trying to create a South L.A. theater scene. When the company formed, LaBeouf tweeted a video calling for new members, and anyone with a story to share was welcome. “I’m tryin’ to change the world. If you are too, let’s get it. Bang!” he said in the video.

More than 200 people showed up to the first workshop. In January 2019, the company decided to accept only new members who were residents of South L.A, where Soto and Johnson grew up.

“We wanted to give back,” Johnson says, “to create something in the neighborhood because there’s no opportunity here for this kind of thing, theater.”

Dramatizing the health crisis, an urgent moment in history, was important, Soto adds.

“The world wants to know what’s happening to these workers who are actually putting their lives on the line every day to test people,” he says. “What kind of interactions can you have? How can we uphold kindness and generosity and humility throughout times like this when everyone’s panicked and fearful?”

“5711 Avalon” was also a way to offer COVID-safe live entertainment. Audience members will be asked to stay inside their cars and to wear a mask if they have to go out (bathrooms are nearby). They will be encouraged to keep windows rolled up but for a few inches for fresh air.

On this rehearsal night, the most heightened drama is coming from LaBeouf. A technical snag has sent him spiraling.

“No! What is this, dog? You got every cue wrong tonight!” LaBeouf screams at a tech crew member. “Figure it out!”

He gathers all the actors into a circle for what appears to be a public shaming.

“Let’s talk about this in front of everyone, the whole cast, all the actors,” LaBeouf says. “Every f— ing cue! And in front of the L.A. Times! Hold that, own that! Don’t embarrass me in front of the whole world!”

Seconds later, two Times staffers are brusquely escorted off the set.

“Bye L.A. Times, thanks for coming!” LaBeouf hollers, a crooked smirk fixed on his face. “See you opening night!” He waves goodbye exaggeratedly.

The cast and crew seem unfazed by LaBeouf as he rages on.

“He’s just passionate about his art and wants to get it right,” a young woman associated with the production says sweetly, though we aren’t able to get her name before being whisked away. (One company member, who asked not to be named, said in a follow-up phone interview that the production was proceeding smoothly in the days leading to opening night and that no one had quit because of LaBeouf's behavior. “Everything’s fine, we’re good, we’re making art,” she said.)

Outside, ambient light from the play’s screens spills onto the sidewalk as the audio fades in and out. Car doors slam in the distance.

One thing is clear: Even in the face of the coronavirus and with a “passionate” celebrity at the helm of this production, the show will go on.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.