A drought so bad it exposed a long-ago homicide. Getting the water back will be harder than ever

As a metaphor for the uncomfortable truths this drought has laid bare, the body in the barrel is grimly apt.

At some point in the mid-1970s or 1980s, someone tipped a metal canister containing the remains of a male gunshot victim into Lake Mead. At the time, the barrel sank through hundreds of feet of cold Colorado River water before settling on the muddy bottom of the country’s largest human-made reservoir.

Now the lake is emptier than it's ever been, and the consequence of those decades-old actions are no longer obscured. The water level has plummeted, leaving ghostly calcium deposits along the lake’s rocky shores. On Sunday, police say, boaters spotted the rusted remains of the barrel and its occupant on a sun-scorched stretch of exposed mud.

Homicide victims weren’t what scientists serving on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change had in mind back in 2001 when they warned of the “imaginable surprises” an altered climate might yield. But the historic megadrought that has drained Lake Mead of its water and its secrets meets their definition: a stunning and unpredictable event that’s nevertheless within the realm of a warmer world’s unsettling new possibilities.

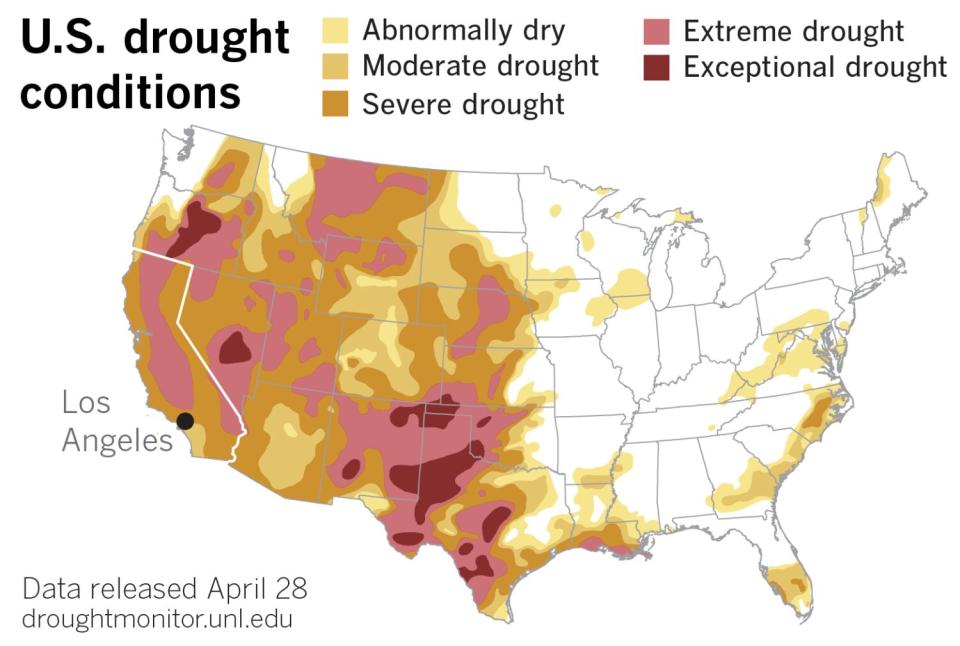

This drought, the worst on record, is the result of many factors, some flukes of nature and others the consequences of human activity.

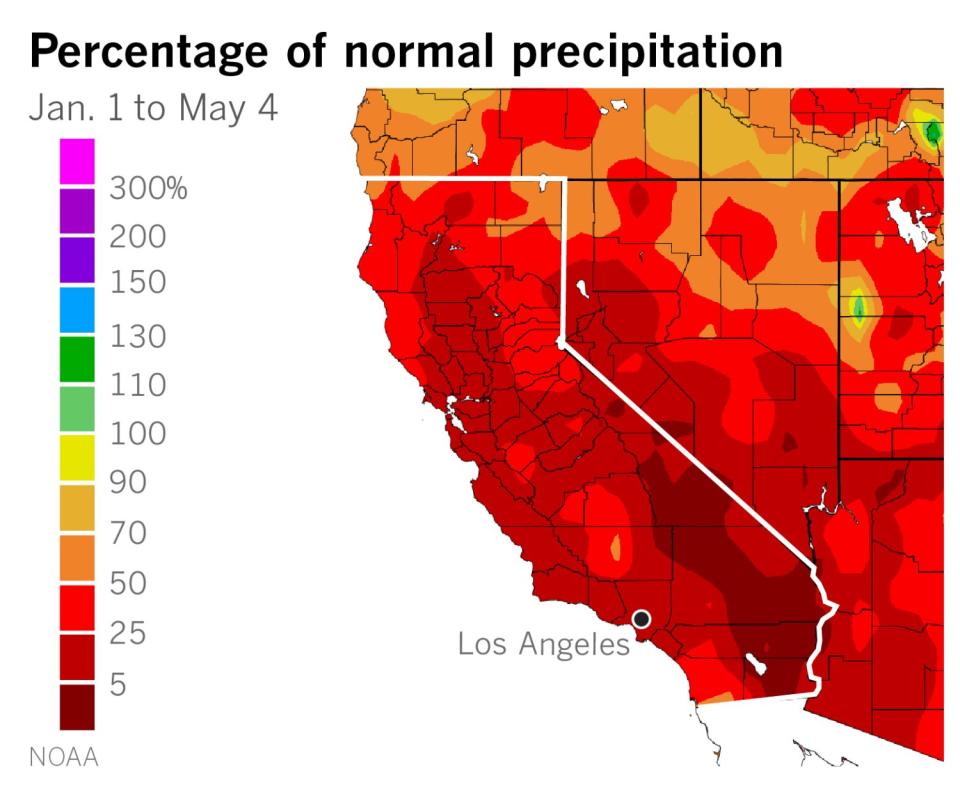

Average summer temperatures in California are 3 degrees higher now than they were at the end of the 19th century. Less snow falls, which means the volume of water feeding streams and reservoirs is 15% to 30% lower than in the mid-1900s.

There have been stretches of dry years in this part of the world as far back as the climatological records go. But global warming has escalated the current dry period into disaster territory.

Humans aren't the only ones in need of more water. Parched vegetation and soil must also now compete with a thirstier sky, thanks to atmospheric changes brought about by decades of steady temperature increase.

A warmer atmosphere holds more water, and the warmer it gets, the more water it wants — regardless of need on the ground. In a study published last month in the Journal of Hydrometeorology, researchers combing through 40 years of data found that the atmosphere across the continental U.S. now demands a greater share of water than it used to, especially in the West.

The effect isn't linear: as the planet gets hotter, the sky gets even thirstier.

“As the climate is warmed, that pull of water from the land surface into the atmosphere essentially becomes more forceful,” said study leader Christine Albano, a hydrologist at the Desert Research Institute in Reno.

That increasing force means it takes more water today than it did 40 years ago to provide plants with the same level of hydration. The Rio Grande region that covers parts of Colorado, New Mexico and Texas now needs 8% to 15% more water to get the same irrigation result, the researchers calculated. The effect is slightly less in California but still present, Albano said.

More than half of this increased thirst was due to increased temperatures, the authors found. Other factors included changes in humidity (26%), wind speed (10%) and solar radiation (8%).

Unlike earthquakes and hurricanes, the onset of a drought can’t be pinned to a day or an hour. “It’s one of these creeping disasters,” said John Abatzoglou, a UC Merced climatologist who worked on the study with Albano.

Drought manifests in several different forms that don’t always happen at the same time: decreased rainfall, low stream and groundwater levels, thirsty crops, insufficient community supplies or struggling ecosystems.

“When it starts to feel really bad is when all of those types of drought are essentially happening at the same time. And that’s kind of where we’re at right now,” said Faith Kearns, a scientist with the California Institute for Water Resources in Oakland.

It didn't get this way all at once. The American West is in the hottest and driest 23-year period in at least the last 1,200 years, said Park Williams, a UCLA climate scientist.

Thanks to a combination of higher temperatures and insufficient rainfall, the soils of southwestern North America were more parched between 2000 and 2021 than in any other 22-year stretch since the 800s, surpassing a similarly arid period in the late 1500s, Williams and his colleagues reported in a study published this year in Nature Climate Change.

Williams has updated the data to include the present year through March. Even if we get an average amount of precipitation through the summer, 2022 will join 2002 and 2021 as the three driest years in the last century, and most likely the driest since the 1700s, he added.

“We’ve had three of these ‘driest-in-the-last-300-years’ years in the last two decades,” he said.

In their study, Williams and his colleagues determined that the increase in temperatures was the single biggest factor in the current megadrought, shouldering 42% of the overall responsibility. "Regular old bad luck" reduced rain and cloud cover, he said. But without climate change the natural fluctuations of the last few decades would not have qualified as a megadrought, the authors wrote.

What’s more, the most comparable megadrought in the historical record — that late-1500s event — started to lose intensity as it entered its third decade.

That's not happening this time.

“This drought that we’re in now, rather than showing signs of petering out, doubled down last year and then doubled down again this year,” Williams said. “This drought is going as hard now as it ever has.” Temperatures are still high. Rain still isn't falling. There are no signs that relief is coming any time soon.

Recovering from this drought will take more than a single wet winter. Given the parched conditions on land and the increased demand in the atmosphere, we'll likely need multiple seasons of heavy precipitation to make up for the current water deficit, Albano said.

California gets up to 50% of its annual precipitation from the atmospheric rivers that redistribute water vapor from the tropics to the poles. These rivers are expected to become more erratic as the climate changes, with fewer storms that are far more intense and destructive. Global warming is also disrupting the El Niño cycle, again concentrating rain in fewer, more aggressive storms.

Predicting exactly when those things will happen is about as impossible as knowing when the next earthquake will hit.

There are bound to be wetter years than this one at some point, climate scientists say, but that doesn’t change the underlying trend toward hotter temperatures and more arid soils.

“Whatever was normal — not that there is much normal — is certainly shifting,” Abatzoglou said. “How we prepare for this is becoming a really challenging question for all walks of life that are dependent on water, which is everybody.”

Just as there has been a fundamental shift in average temperature, the public may need to fundamentally reshape its expectations of water availability.

This drought is unprecedented in modern times, but not unanticipated. In that IPCC report from two decades ago, the authors predicted that if we did nothing to halt climate change, we’d see exactly the kinds of conditions the West is experiencing now: higher daily average temperatures, more heat waves, longer and more frequent droughts, poorer water quality, and more forest fires.

Meanwhile, Las Vegas police say they expect to find more bodies as Lake Mead continues to recede. Many facts people would rather not face are coming to the surface.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.