The 'drowning machine': Aging low-head dams in Kentucky, across the US are killing hundreds

CYNTHIANA, Ky. ― Beth Collins suggested they go to the dam that sunny day in 2011.

After weeks of rain in northcentral Kentucky, the skies had cleared, so Collins and her boyfriend, Brandon Holbert, could finally get outside and do something.

The South Fork Licking River was the usual hangout spot for Collins, then 21, and her friends. Families would come to swim and fish near the dam. There was even a rope swing.

But the river was moving fast that day, rushing over the concrete dam, making it hard to see the structure. They had to walk across its top to get to their favorite spot on the other bank.

“The water was really high,” Collins said. “We should’ve been like, ‘No.’”

The first time, they made it over. But when Holbert, 20, tried to walk back over the dam, he slipped. Collins waited for him to get back up.

“But he didn’t,” she said, “I didn’t know what to do.”

A friend and a nearby fisherman rushed downstream and pulled Holbert out of the water. Beth ran to him, screaming. She tried to give him CPR, thinking she might know how to do it. She didn’t.

Holbert was gone.

More:Kentucky is getting wetter as climate change brings an era of extremes, data shows

Explaining the fatality of low-head dams

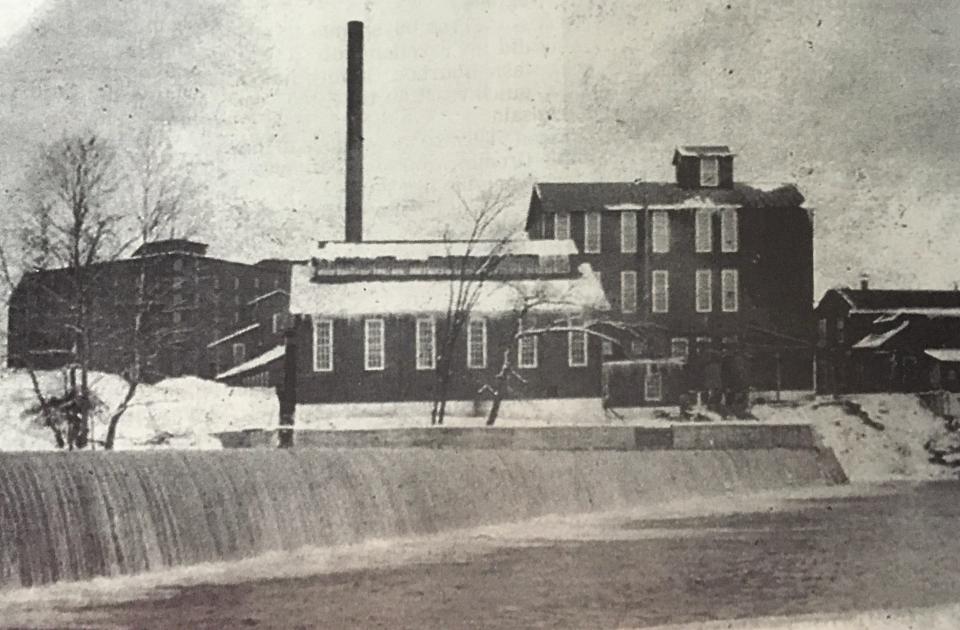

Holbert’s death was one of the hundreds of cases of Americans who have died after getting sucked into a “low-head” dam, a style used in the late 1800s to power mills and distilleries. More than 10,000 were built around the nation and remain in place. They are not very tall, which gives them their name, reach from bank to bank and can be difficult to see from upstream. Many are no longer needed, but they are still capable of pulling swimmers and kayakers to their deaths.

In August, a man drowned in Scott County while rafting with his 17-year-old son near the Elkhorn Creek low-head dam. It was the second drowning death there in 15 months.

At least 37 people have died in Kentucky at the site of a low-head dam, and at least 1,400 people have died nationwide.

But the true number is unknown because there are no federal or state agencies responsible for maintaining an inventory of low-head dams, repairing them or keeping track of the people who die.

“Many of the dams are really orphaned,” said Manuela Johnson of the Association of State Dam Safety Officials. “Nobody seems to claim ownership of them. But they’re still there.”

Johnson said the dams are killing people far beyond the U.S. For example, she estimates six or seven people die daily in India.

“I have a Google alert set up with two words: dam and drowning. And I get a report every day,” she said.

Low-head dams look small and picturesque, but they can kill even in seemingly calm water.

As water flows over the dam, it falls into the river below and spins like a washing machine. Anything nearby can get trapped underwater. That unique current is so lethal, it’s been dubbed the “drowning machine.”

“It’s like giant arms reaching out and grabbing hold of you and pulling you towards the dam,” said Dean Peak of Harrison County.

Peake once saved a person trapped by a low-head dam, saw another man die, and was sucked into one himself during a separate incident but managed to escape.

“Once you get close enough where the water pulls you in, it takes you under. Then you start rolling and rolling,” he said.

Re’Jeana Craft, a member of the Harrison County Search and Rescue Team, said it took a team of 63 people nine days to recover one victim.

“[The water] hits you across this dam, jerks you back up and then just keeps doing that over and over,” said Craft, who has responded to every low-head dam drowning in her county for the past 20 years. “That will rip your clothes off of you. Rip your skin off. It breaks your bones.”

Working in a small community like Harrison County, members of Search and Rescue often know the victim or their families. But even if she knows someone, Craft can have a hard time identifying the victim after she pulls them out of the water.

“It doesn’t look like you when you’re done,” she said.

More:Big changes are in store for Daniel Boone National Forest. Why conservationists are worried

Working to eliminate the ‘drowning machine’ effect

In 1991, Rollin Hotchkiss, a professor of civil and construction engineering at Brigham Young University, gave his students an academic challenge: Figure out how to make low-head dams safer. They couldn’t do it.

The next year, Hotchkiss posed the same problem to his new students. They couldn’t do it either.

“It turns out to be the most challenging design I’ve had to work with in my career,” Hotchkiss said.

Almost 30 years later, Hotchkiss and fellow academics say they have finally found a solution.

They designed a structure that sits on the downstream side of the dam that resembles a staircase. Water gradually flows over the staircase rather than falling straight down and creating the “drowning machine” effect.

It eliminates the dangerous currents and protects victims from being severely battered, he said.

Hotchkiss’ design has been successful in lab tests, but he hasn’t secured funding to test it on a real dam.

More:Are fish from Kentucky lakes, rivers safe to eat? New state guidance details the risk.

In the meantime, private firms and government agencies have developed and implemented other designs intended to make low-head dams safer.

All those solutions face the same hurdle: funding. Communities have only three convoluted options to pay for them.

The first is litigation. Multiple lawsuits following drownings have forced dam owners to make safety improvements, Hotchkiss said.

In one case, the Parkin family in Utah successfully sued the state, the county and the company that owned the dam after Warren Brent Parkin drowned at the Brighton and North Point Irrigation low-head dam.

The family received over $600,000 from the state and county, and the county will now be required to put up signage to warn about the dam.

Hotchkiss said dam owners sometimes avoid preemptively fixing their dams so they’re not held liable for drownings. For the many dams that don’t have owners, victims don’t know who to sue.

The second major source of funding isn’t to protect humans, but fish.

Government agencies, including U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and its state equivalents, spend money to clear rivers for fish populations moving upstream. Since low-head dams block rivers, this funding has been used to remove them.

If safety projects like the “staircase” design create fish passageways by coincidence, they might be funded, as well, Hotchkiss said.

The city of Cynthiana is taking the third option: Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) funding.

The challenge with that approach is that FEMA is most likely to approve an application only when a dam owner proves that a drowning at a low-head dam was the result of a natural disaster, according to grant writers hired by the county.

Steve Maggard, a Lexington-based civil engineer with Summit Engineering, Inc., had worked on low-head dams in West Virginia. When he learned about Cynthiana’s dams and drownings, he approached the mayor with an idea: Summit Engineering could install rock ramps on the dams to make them safer.

But they needed over $2 million for the project, which is a lot for a small community.

More:Kentucky to get $25M to plug old oil and gas wells. Here's what it means for jobs, climate

Maggard and Cynthiana Mayor James Smith hired grant writers with the Bluegrass Development District to find funding. The grant writers identified a 2018 flood event and argued that a drowning that year was the result of the elevated waters.

The grant writers submitted their application to FEMA in September. Kentucky Emergency Management has included Harrison County’s application on its list of prioritized projects, but the power of approval still lies with FEMA.

Cynthiana Mayor James Smith is surprised it’s even gotten this far.

“I said, ‘sure,’ not thinking,” Smith said. “I didn’t expect them to actually find the money to do it.”

After years of lobbying from dam safety and recreational organizations, low-head dams are also getting some attention from Washington.

The 2023 Water Resources Development Act would require the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to establish a low-head dam inventory. That would finally provide accurate data about where low-head dams are, but the bill still does not assign responsibility of the dams to any government agency.

As of early September, both the U.S. House and Senate have passed their own versions of the WRDA.

Indiana moves to inventory, address low-head dam dangers

Until then, Hotchkiss and a nationwide team of student researchers and volunteers are making their own inventory.

They use Google Earth to zoom in on rivers and look for low-head dams. They place a green pin if they’re confident it’s a dam, and a yellow or red pin if they’re uncertain.

Manuela Johnson, who is part of the inventory task force, said the team includes students from Utah State University, a retired U.S. Army Corps of Engineers employee and a Kentucky-based Boy Scout troop.

The next step is more difficult.

Accredited engineers must inspect each possible dam to verify they are, in fact, low-head dams. That process can take months because it relies on finding engineers to volunteer their time.

More:Biden promised billions for environmental justice. What could that look like in Kentucky?

An ongoing review of low-head dams in Kentucky, led by one of Hotchkiss’ students, has been in the works for months.

When each state database is complete, they are handed over to state legislators who decide what to do next.

“The state may say, ‘Well, thank you very much, we’ve needed this information,’” Hotchkiss said. “Or a state may say, ‘This conversation didn’t occur; we don’t want that.’”

Legislators in Indiana, for example, with lobbying from victims’ families, have made the state a leader in low-head dam safety by requiring signage and liability insurance, and giving local authorities the power to remove people who get too close to the dams.

Indiana and Colorado have followed Hotchkiss’ approach and created their own low-head dam inventories.

But most states have done little, leaving advocacy groups and private citizens to do the work of warning their communities.

After joining Harrison County Search and Rescue, Re’Jeana Craft visited middle schools to teach students about low-head dams. She showed them the tools used to recover bodies: a curved shepherd’s hook, or a metal bar with large fishhooks to grab hold of skin or clothes.

“I know you live there,” Craft tells the students. “I know your parents take you down there. And I know you think, ‘Oh, my parents live there, they did it, too.’ But it just takes just once.”

After the drowning of his brother and father at a low-head dam in 1997, Kenny Ratliff pushed the city of Cynthiana to put up warning signs about the dam.

He and his family visited the mayor and other city officials, even offering to pay for the signs. For a while, Ratliff was doubtful anything would get done.

“A typical government response is pretty slow,” Ratliff said. But eventually, the city agreed and put up two signs. Someone sent Ratliff pictures of the signs, but he’s never gone back to see them.

Some survivors, victims' families work to raise awareness

Sometimes, though, victims’ families do go back to the dams.

Shawna Caldwell, Brandon’s sister who was also at the dam when he died, returned to the river two days after the accident. She saw families swimming and fishing near the structure.

“Like it never happened,” Caldwell said. “And that, I think, is what got me so much more emotional and so much more headstrong about wishing things could change out there.”

For a while, she would comment on pictures posted online by people visiting the dam. She would write that it wasn’t safe to be there and asked if they remembered Brandon.

After a decade of feeling like no one was listening, she gave up trying.

Beth Collins also goes back to the dam from time to time. She’s often alone, sitting in her car. But one time, she saw a man and his two small children standing on the dam to fish.

“People have died here,” Collins told the father. “That was the first time I got out (of my car) because I was like, ‘I can’t sit here and watch this.’ And he was just like, ‘Oh, no, we’re fine. It’s not that deep.’”

Interested in helping with the low-head dam inventory efforts? Contact Dr. Rollin Hotchkiss at rhh@byu.edu. His team is especially looking for people in each state who can take pictures of the dams to confirm their location.

This article is part of a collaboration between The Courier Journal and Boyd's Station, a Kentucky non-profit that provides emerging artists and student journalists a rural place to hone their craft. Sarah Hume was the recipient of the 2022 Mary Withers Rural Writing Fellowship grant at Boyd's Station.

This article originally appeared on Louisville Courier Journal: Low-head dams across U.S. are trapping, killing hundreds