Drug addiction and the criminal justice system no match for Knoxville's Reico Hopewell

Editor's note: This story discusses self-harm. If you or a loved one are at risk, contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for support at 988 or 800-273-8255.

In the 1990s, crack cocaine ignited mass incarceration, especially of Black men, devastated families and spread like wildfire across America. The complex dynamic of that era nearly took the life of a man that many in Knoxville say stands for the true meaning of “But God.”

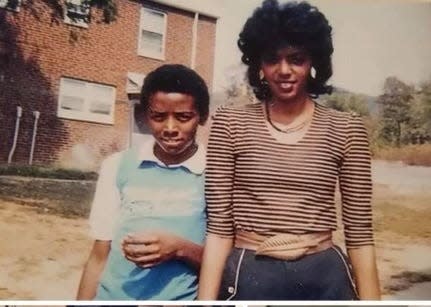

Reico Hopewell, now 50, never forgets his humble and scary beginnings. He reflects on an early life of trauma, growing up in East Knoxville’s Austin Homes housing projects and the 15 years he fought to simply stay alive, addicted to drugs, walking the streets begging for food and eating out of trash cans.

And, on some days, not wanting to wake up.

“I was that man you see walking downtown panhandling and talking to himself,” Hopewell told Knox News.

“In 1991, I tried to commit suicide for the first time. I tried to take my life four different times during the course of my life, I was fighting those inner demons, and the guilt and shame resurfaced over and over again due to substance abuse.”

Many ask how a man who now sits on some of the city's most prestigious boards ‒ earning numerous accolades and the title of CEO - turns his life around and lives through circumstances that would have taken many to the grave. He has one answer.

Prayer.

And grace in the form of many "last chances" from the people in his life.

There wasn’t some defining moment or situation that made him finally say enough is enough. It was the simple act of falling to his knees and asking God to take the taste of crack cocaine from his mouth.

“I haven't used since that day in 2008. And my life went up from there,” Hopewell said.

How it all began

Hopewell was born in 1972, living his early years with his grandmother and his mother, who was only 14 when she became pregnant. His father, a 20-year-old man, lived in the same housing projects.

“It seems like almost everybody was raised by their mom in my neighborhood, single moms, but my mom worked hard to provide for me. We didn’t seem poor to me growing up, but we were, and we just made the best of what we had,” Hopewell said.

After high school, Hopewell’s mother went to Knoxville Business College and eventually was hired by Knoxville's Community Development Association and TVA. In 1979 she put herself into a position to move Hopewell to a neighborhood in what many considered back then to be advancement: West Knoxville.

Hopewell was faced with a reality he wasn’t familiar with in the old projects.

Racism.

“You know it was like you're trying to get away from the problems and the trauma, but for Black people, West Knoxville wasn't always kind, at least to me.”

The culture shock included years of bullying, being chased home from the school bus, being called racist names and experiencing microaggressions, all over being a tall, dark-skinned boy.

Those experiences stayed with Hopewell for years, even affecting the friendships he cultivated there.

“I had to educate some of them on why the N-word was offensive to me or why quoting lyrics from a rap song in my presence wasn’t OK. Some of them never even apologized, so I had to ask myself, 'Do they care?'”

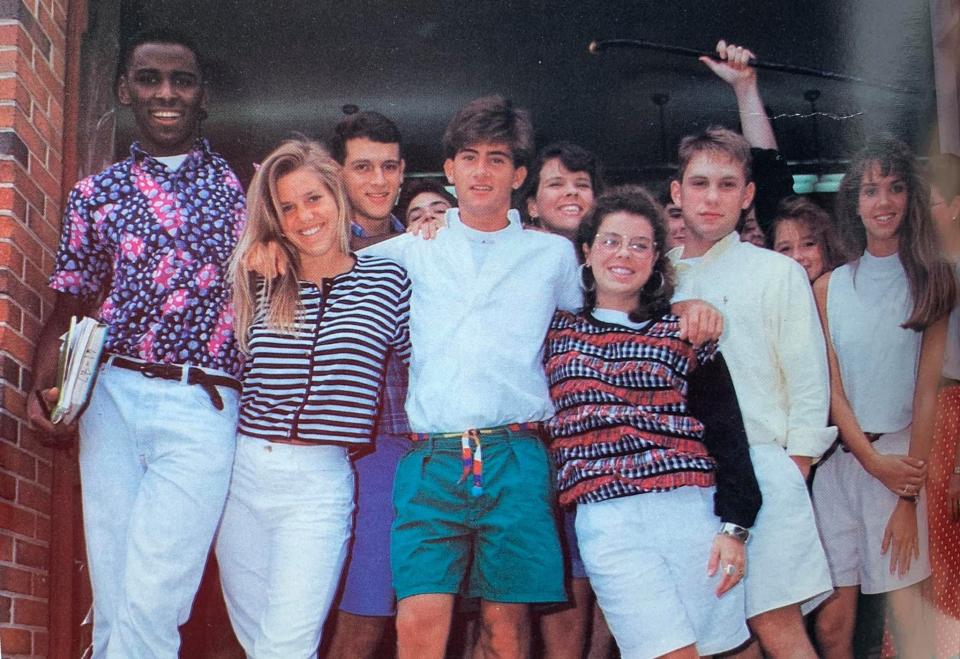

While attending Bearden Middle School and eventually Bearden High School, he ran track as an outlet. He played basketball, too, and he quickly became a star player since he towered over most of the other boys at 6’5.

A story like 'The Blind Side'

Money was tight, and Hopewell’s mother was unable to afford the costs of basketball camp to expand his talents, so the parents of one of his closest friends stepped up.

In 1989, Sam and Ann Furrow, a fixture in the Knoxville business community, took Hopewell into their home.

Sam Furrow was instrumental in starting several businesses, including automotive, heavy equipment, auctions and real estate development, primarily in the Southeast. The couple founded Furrow Automotive Group, owning dealerships such as Mercedes of Benz of Knoxville and many others.

Ann Furrow told Knox News that being in a position to be able to help has always been a blessing, and there was something special about Hopewell. Her son Jay's friendship with him meant frequent visits to their home after basketball practice and overnight stays. The two were inseparable.

Ann knew of the challenges Hopewell was going through and his mother's hardships, so she offered her help by allowing Hopewell to live with them on a permanent basis.

"I knew when he moved his boombox in, he was here to stay for a while," she laughed.

Hopewell lived with the Furrow family for two and a half years.

"We were committed for the long haul. Reico went everywhere we went, and sometimes his mother came along with us. He worked for us, he drove our cars, we treated him as if he were our own son," Ann Furrow said.

Hopewell had his own private challenges during that time.

"I was going to Cherokee Country Club when Black people were hardly even accepted there. But I will never forget being told by my high school teacher, 'Reico, don’t forget where you come from. Just because you are living with this rich family and drive a Mercedes, you are still Black,' and that really kind of hurt me,” he said. "I began to feel like I was doing something wrong by living with this family.”

Their help mattered, but it was no match for the pain and trauma of his childhood. He graduated high school in 1991, and despite the athletic success that led to a full-ride basketball scholarship to Maryville College, he started drinking heavily. Hopewell said it was the failure to prepare for college that led him down the path.

Numerous overdoses on prescription pills, and psychiatric hospital stays followed.

Bad decisions followed by a party Hopewell hosted at the Furrows' home while they were out of town led to the couple making the painful decision to part ways with him.

“I eventually found myself homeless,” he said.

In 1992, Hopewell’s father was murdered, and his son spiraled out of control. The two weren’t close, but the loss hit him hard.

“After that, I went to Florida with some of my college friends, and that was the first time I tried crack cocaine. I was 19."

That was it. That car ride led him down the road to addiction. Fifteen years spent hooked on crack cocaine, homelessness, and more arrests than he can count for theft, vandalism, shoplifting, writing worthless checks and robbery, all in an effort to chase his next high.

“During the crack epidemic, they were throwing the book at Black males. I tell people I have been in and out of prison and jail more times than most of our police officers have ever seen one man be institutionalized. My criminal record runs off the page. All my crimes were ways to get access to more drugs,” he said.

Another chance from his loved ones and promise of redemption

With access to drugs in prison, the cycle never stopped.

“A lot of people think being locked up is a way to rehabilitation. But drugs are readily available in there as it is in the free world. Prison is the first time I saw someone inject drugs.”

In 2007, after prison and dozens of stints in Knox County's jail, one last charge became the moment where grace would have to step in.

“I was in jail facing a 25-year sentence as a repeat offender, and I remember going in front of the judge who held my life in his hands, and I just asked him for one more chance. Just one.”

The judge obliged.

“He allowed me to go to treatment, and after being released, I spent more than 2.5 years in the E M Jellinek Center, it’s a halfway house, and I did everything I could to turn my life around.”

Today, Hopewell is a board member of the same halfway house.

Getting a new start

When Hopewell was homeless on Knoxville’s streets, he spent a lot of time at the downtown Hilton, where he would go inside to warm up or use the phone.

Never imagining as a man with multiple felony convictions he could get a job anywhere, much less the Hilton, he was given an opportunity by Brent Owen, one of the managers.

But he took the job and ran with it for years, moving from housekeeping to concierge services, never late or missing a day.

He threw himself into more work by landing a second job at Cornerstone of Recovery, an inpatient facility for those suffering from substance abuse.

“I was given many chances by a lot of good people who believed in me even when I didn't believe in myself, when I didn't love myself.”

Addiction plagues Black communities, surpassing gun violence

Hopewell says so much emphasis is placed on gun violence in Knoxville's Black communities, and rightfully so. But drug overdoses are taking more Black lives than guns.

“We don’t really talk about this addiction issue in the Black community like we should. There's a stigma in our community. I know so many who are using and dying young, even here in Knoxville. Black people, you know we go to church for our problems, but I believe prayer is a weapon, but counseling is the strategy.”

Unfortunately, research shows African Americans have lower rates of recovery from drug addiction following treatment due to social and cultural factors.

Arrest rates are higher, too. Five percent of illicit drug users are African American, yet African Americans represent 29% of those arrested and 33% of those incarcerated for drug offenses. This leads to major roadblocks in treatment because there is fear in self-reporting, according to a report from the NAACP.

Drug addiction spans socioeconomic and financial status

Drug abuse for a long time has been associated with poverty, but Hopewell says it's a myth that he has uncovered through his work and years of knowing others struggling with the disease.

“I’ve had people come through my doors who once were the same people I was in front of when I was facing my own struggles and begging for mercy. Helping some of their family members with the same problems. You can get opiates online. This issue has no identity. It can affect anyone. I’ve done so many crisis interventions in affluent neighborhoods that it's overwhelming.”

In 2020, 3,032 Tennesseans died of a drug overdose, up 45% from 2019. Drug overdose deaths in Tennessee have consistently increased over the last five years, but the change from 2019 to 2020 represents the greatest year-to-year increase since this period began, according to a Tennessee Department of Health report.

Hope is in his name

Today, Hopewell dedicates his life to helping men who were once just like himself battling addiction. He urges them to turn their lives around with the same compassion and mercy he was granted by a few special people.

He's a licensed alcohol and drug abuse counselor with numerous certifications and opened his Mend House Sober Living in North Knoxville in 2015, a complex that provides shelter, jobs and treatment. To date, he has helped more than 700 recover their lives from substance abuse disorders.

“I had a list of things I wanted to do in my life, and this was a goal of mine. To help others who are battling these issues.”

In the meantime, the Furrow family reunited with Hopewell 26 years later, and another family from his childhood came back into his life to help him to raise funds for Mend House.

"I remember our son telling us, 'Mom, I think Reico is doing better, he is doing some positive things.' Reico never tried to reach out to us, but we thought about him all the time," Ann said.

In 2017, Hopewell reached out to seek closure. The family met and rekindled the close relationship they once had.

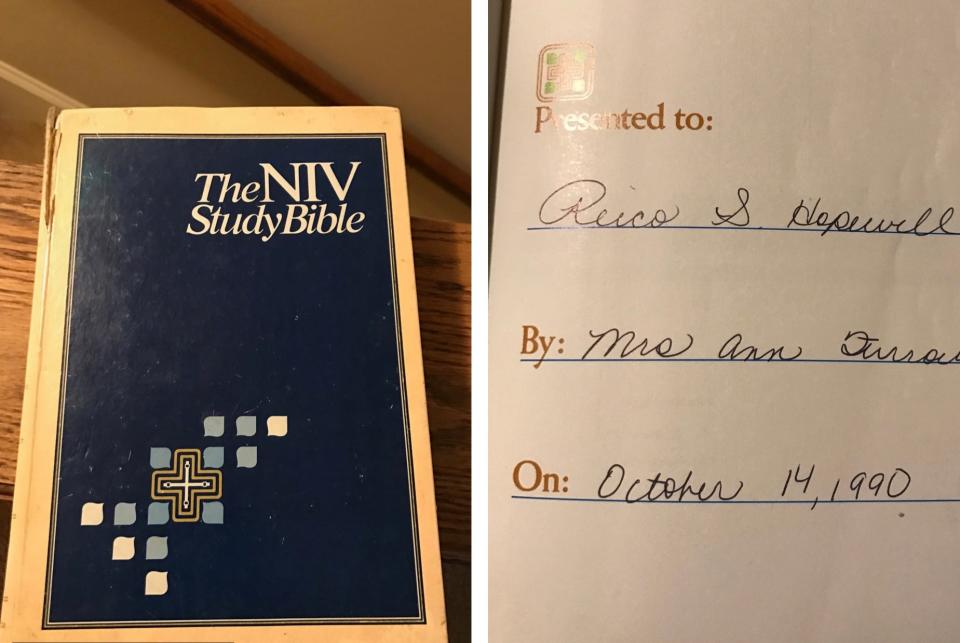

The one item Hopewell kept with him all of those years of being homeless was the Bible Ann gave him in high school.

"You can change. Reico's life is a testimony to that. He's forgiven. His record is wiped clean due to his faith in God," Furrow said.

Hopewell is in the process of completing the bachelor's degree he never got through Morehouse College’s new distance learning program. He was one of the thousands of applicants selected for the inaugural class.

Hopewell is now part of the same village of people who saved his life. Now he is saving others.

“I’m on the front lines out here, and I’m going to keep going to help youth and the Black community. These accolades I am getting aren’t for me. They are to give away to help someone else. And that's my ultimate goal.”

Angela Dennis is the Knox News social justice, race and equity reporter. You can reach her by email at angela.dennis@knoxnews.com Follow her on Twitter @AngeladWrites; Instagram @angeladenniswrites; and Facebook at Angela Dennis Journalist.

This article originally appeared on Knoxville News Sentinel: Knoxville's Reico Hopewell transformed after life of addiction