Will these new drugs, tests treat Alzheimer's disease? Doctors say they show promise.

The science and treatment of Alzheimer's disease are starting to change. For years, doctors had medications that could only treat the symptoms, not the actual disease. Now there are two treatments approved by the Food and Drug Administration, and more studies show promise in both diagnosis and treatments.

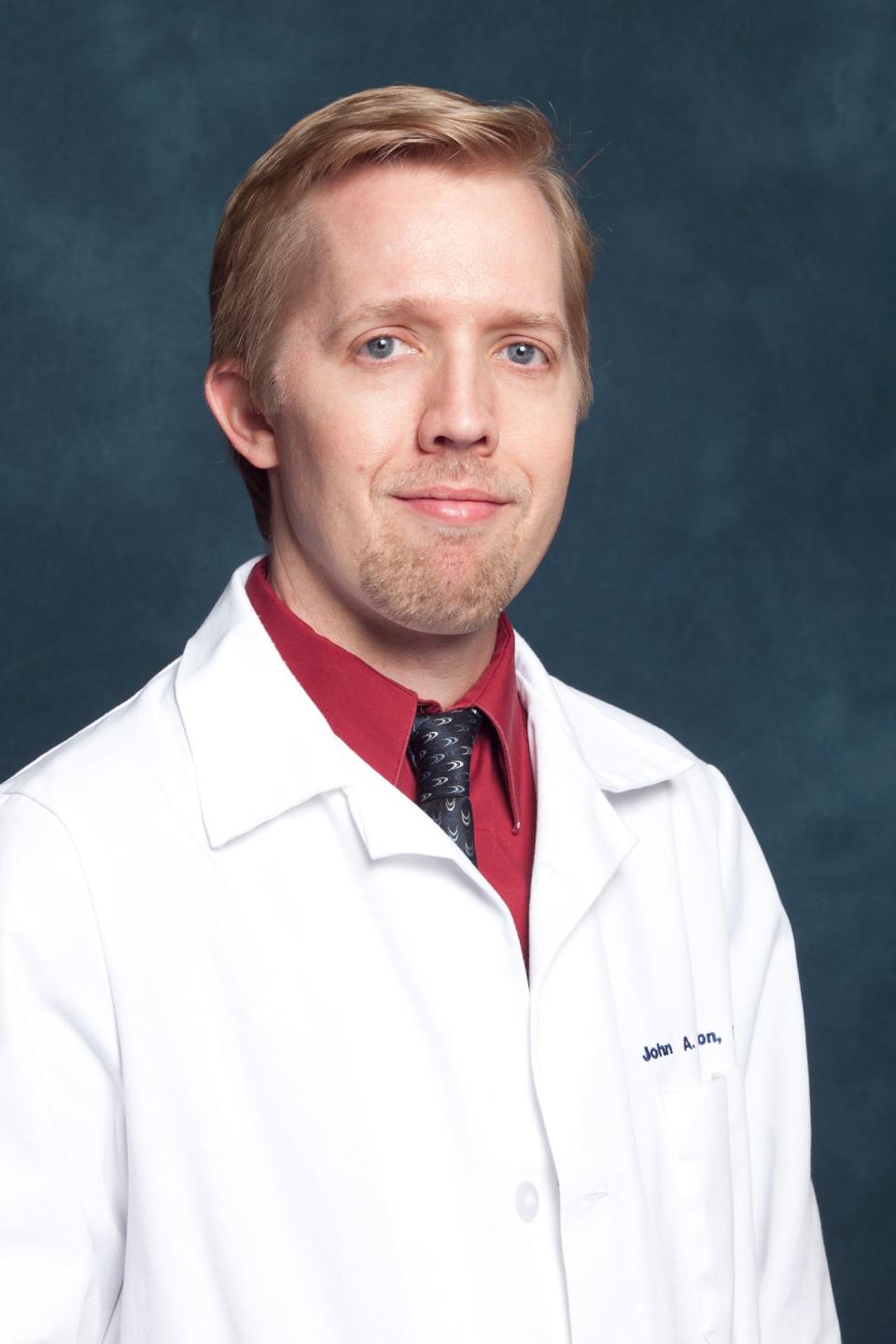

"Every week there is something new that comes out that makes me change what I need to think or what I need to do," said Dr. John Bertelson, an Austin behavioral neurologist who specializes in memory care and an assistant professor at the University of Texas Dell Medical School. "It's really amazing."

Alzheimer's is just one of the diseases that causes dementia. It affects 6.7 million people in the United States and is expected to affect 12.7 million people by 2050, according to the Alzheimer's Association.

We asked Bertelson to walk us through some of the changes and where the science might be headed.

What new treatments are available?

At the beginning of July, the FDA gave full approval for lecanemab-irmb under the brand name Leqembi. This medication has been shown to slow the cognitive decline in people with the disease by 27% in clinical trials.

"This gets to the root of the disease," Bertelson said.

Leqembi goes after the amyloid beta plaques, a protein that is found at abnormally high levels in the brains of people with Alzheimer's. Amyloid is one of two proteins involved in Alzheimer's, tau being the other one.

Leqembi is the second treatment approved by the FDA that works on treating what causes Alzheimer's, not just the symptoms. In 2021, the FDA approved Aduhelm (aducanumab), but doctors have had concerns about its safety and efficacy.

More medications like these are on the horizon. Eli Lilly is working on getting approval for donanemab, which the manufacturer says slows cognitive declines by 35%.

What are the drawbacks for Leqembi?

To qualify for Leqembi, a definitive Alzheimer's diagnosis has to be made rather than basing a diagnosis on symptoms. That means doing a PET scan or a spinal tap to look for an abnormal amount of amyloid proteins. The spinal tap can also track the tau protein.

Not everyone with an Alzheimer's diagnosis can get Leqembi. This medication works best in the early stages of the disease. It also isn't for people on blood thinners, Bertelson said, if they have a pacemaker that is not compatible with an MRI.

The danger of all of these medications is bleeding in the brain.

Leqembi is an infusion given every two weeks. That means sitting in an infusion chair for hours. For some people, it can be a significant hardship, Bertelson said.

It also could cost $26,500 a year without insurance, according to manufacturers Eisai and Biogen. Medicare has indicated that it will cover 80% of the cost of the drug, which leaves 20%, or more than $5,000, for the patient to cover.

The drug manufacturers do have copay assistance. Three of Bertelson's patients have been able to start Leqembi, and they have received copay assistance to make it affordable.

Ongoing research: Dell Medical School researchers trying to understand Alzheimer's disease in Hispanic population

What could be the future of Alzheimer's medications?

These new medications are all delivered by infusions, but Bertelson said eventually they could be given as a shot that patients inject or have caregivers inject for them.

Bertelson views these new medications as delaying the point at which people lose function by a couple of years.

"It could allow them to stay living at home for an extra six months or to drive safely for a longer time. It's more time at a better quality of life," he said.

These medications do not prevent the effects of Alzheimer's from eventually happening.

Bertelson's hope is that in 10 years, we will treat Alzheimer's much like HIV, which uses a cocktail of different medications to prevent symptoms. The current Alzheimer's medications focus on the amyloid protein. Another medication to tackle the tau protein would be needed and possibly one to protect the nerves from degenerating.

"Hopefully, we get to the point where we can significantly slow the disease in its tracks and prevent it," he said.

There's a lot we still don't understand about Alzheimer's.

"We don't know why some people can have amyloid and never get Alzheimer's disease," he said.

How else will Alzheimer's be diagnosed in the future?

A new study from the Netherlands looks at using a finger prick on a card to find biomarkers associated with Alzheimer's. The cards are read at a lab, similar to some of the colorectal exams that detect colon cancer. The study was small (77 participants), but Bertelson said it shows promise of where diagnostic testing could be going.

Even a blood test drawn in a lab would be an improvement from a costly PET scan or spinal tap, or making a diagnosis by symptoms, shown to be only about 80% accurate based on autopsies.

How can people help prevent Alzheimer's disease?

The disease process often begins years before symptoms are seen. People in their 30s, 40s and 50s should be doing these things to improve brain health:

Eat a healthy diet, such as the Mediterranean diet, which focuses on healthy fats and vegetables.

Exercise regularly — both cardio and strength training exercises.

Stay cognitively stimulated with work, home life and hobbies. Learn new things.

Stay social with regular interactions with friends, co-workers or volunteering. A new study pointed out that volunteering can reduce the risk of dementia.

Stay on top of your hearing by getting tested and using hearing aids. Studies have shown that hearing aids promote better cognitive function and decrease cognitive decline, Bertelson said.

Living with Alzheimer's: A valentine of gratitude: Love continues to grow after Alzheimer's diagnosis for Austin couple

This article originally appeared on Austin American-Statesman: New Alzheimer's drugs, testing show promise for treatment, diagnosis