Drunk astronomers, monsters and red underwear: New book explores the myth and folklore of eclipses

An ancient Chinese story tells of two court astronomers, Hsi and Ho, who got drunk and failed to predict an eclipse of the sun. This grave oversight led to them being executed, off-with-their-heads-style, by the Emperor Chung K’ang.

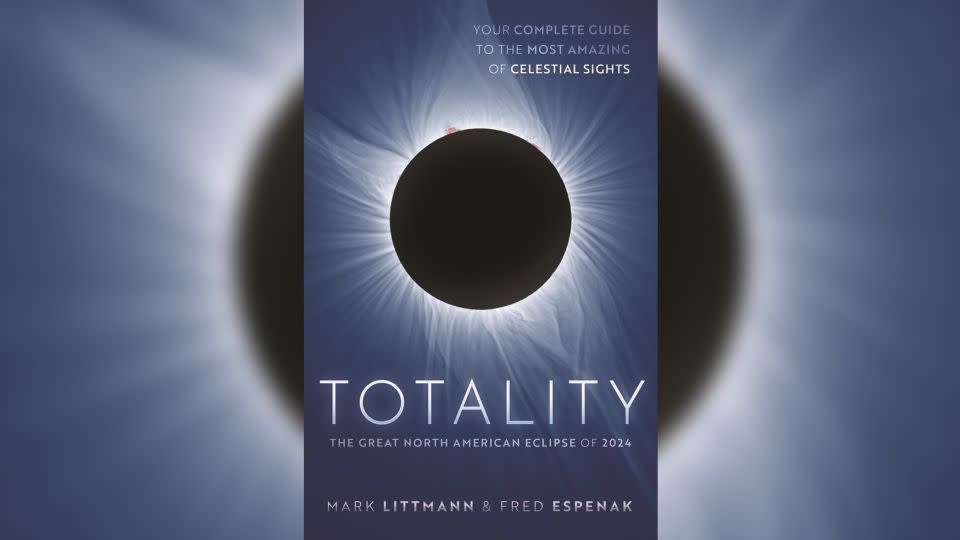

Set sometime between 2159 and 1948 BC, the legend is thought to be the oldest recorded reference to a solar eclipse — and it’s just one of the interesting cultural anecdotes recounted in a new book called “Totality: The Great North American Eclipse of 2024” that was coauthored by Mark Littmann, journalism professor at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, and Fred Espenak, retired astrophysicist emeritus at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

“I find the mythology and folklore of eclipses fascinating,” Littmann said in an email. “To see how people long ago and people today reacted to a total eclipse of the Sun, a sight so unexpected, so dramatic, so surprising in appearance, and so unnatural even though it is utterly natural.”

Such enthusiasm and awe sets the tone for Littmann and Espenak’s evocative book, which also explains the science behind eclipses and how to effectively photograph the upcoming total eclipse of the sun in April 2024 (Espenak is a well-known eclipse photographer who has witnessed more than 30 total solar eclipses). Additionally, the book includes tales from travelers who ventured to the United States from around the world to view the last total solar eclipse in 2017.

CNN spoke with Littmann to learn more about how eclipses have been viewed throughout time, why it matters — and the reverence and superstition these celestial phenomena continue to evoke today.

This conversation has been condensed for length and clarity.

CNN: What do we know about the oldest known references in human history to eclipses?

Mark Littmann: The Chinese were recording eclipses on animal bones as early as 772 BC. By the first century BC, the Chinese had enough records that they realized there was a rhythm to eclipses and could use that rhythm to calculate accurately when a future eclipse would occur — even though most of the solar eclipses would not be visible from their location.

Similarly, from 750 BC on, the Babylonians recorded eclipses in their cuneiform writing on clay tablets. By about 600 BC, the Babylonians noticed that eclipses were occurring at regular intervals, so they used that interval to predict when a future eclipse would take place. Their predictions were amazingly correct. Even today, if we add 18 years and 11⅓ days to the date of one eclipse, we will almost always find an eclipse of the same type occurring at the end of that period.

The Maya — living in Mexico and Central America as early as 2000 BC and flourishing from 250 to 900 AD — developed their own written language and recorded their astronomical observations in books. Alas, only four of those books survived the destruction of the Spanish conquest. One of them, the Dresden Codex, demonstrates that the Maya were able to predict eclipses of the sun by noticing the interval between their appearances.

Interestingly, the Chinese, the Babylonians and the Maya could predict eclipses but did not know what caused eclipses.

CNN: What are some of the most common myths cultures created to explain eclipses?

Littmann: The mythology of eclipses most often involves a beast that tries to eat the sun for lunch. For the Chinese, that beast was a dragon or a dog. For Scandinavians, it was a wolf.

In India, a demon named Rahu lost his body when he tried to steal the nectar of immortality from the gods. But Rahu’s head lives on — and it is very angry. Whenever he can, Rahu chomps on and swallows the sun. But Rahu has no body, so the sun goes in his mouth and comes out his neck, returning brightness to the sky. Rahu never learns and continues pursuing and chewing the sun and moon, causing eclipses.

Not all cultures explained eclipses as a monster swallowing the sun or moon, however. Some peoples of northern South America said the sun and moon periodically fight one another, temporarily shutting off each other’s light.

But the violence of these stories was not always in the sky. Folklore from Transylvania (central Romania) says that from time to time the sun looks down on Earth and sees how vicious and corrupt human beings are. The sun turns away in disgust — and that’s a solar eclipse.

In at least one culture, eclipses were not acts of celestial or terrestrial violence at all. The Fon people of western Africa said that the male sun rules the day, and the female moon rules the night. They love each other, but they are so busy traversing the sky and providing light that they seldom get together. Yet when they do, they modestly turn off the light.

CNN: What modern day myths and superstitions still exist surrounding total eclipses?

Littmann: Myths from long ago show that most people thought eclipses were dangerous events, with Earth in peril of losing its light and warmth. Even in more modern times, if people don’t know what causes a total eclipse of the sun or when it will happen, the daytime disappearance of the sun evokes confusion and terror.

In 1918, 13-year-old Florence Andsager was playing with her brothers and sisters in the yard of their family’s farm in Kansas. In the middle of the day, the sky began to darken, even though the sky was clear. Their mother screamed for them to come into the house, and she, her husband and the kids huddled together. They thought the world was coming to an end. It was a total eclipse of the sun.

As recently as 2012, when an annular (not-quite-total “ring of fire”) eclipse of the sun was visible north of Sacramento, California, a pregnancy blog shared how some Hispanic mothers told their pregnant daughters that, in case of a solar eclipse, they should wear red underwear with a safety pin attached to it over their bellies to protect the fetus from birth defects. No red underwear? Any color underwear would do if the mother-to-be attached a red ribbon to it. The tradition also cautioned that pregnant women must not go outside during the eclipse.

CNN: How do the ancient traditions you’ve learned about regarding eclipses play into your personal experiences of seeing them today?

Littmann: I keep asking myself: If I lived long ago, how would I react to a total eclipse of the sun if I didn’t know it was going to happen — and how would I go about trying to understand what I saw so I could pass that understanding on to others. I come away from that exercise with a greater appreciation of how ancient people coped with that experience.

Many of their stories told of some monster eating the sun, which is actually a very good description of what the partial phases of an eclipse look like. And such a description is hard to forget.

I’m amazed by the care and dedication of the ancient Babylonian, Chinese and Maya astronomers who observed and kept records of eclipses for generations even though their own lives would not be long enough to give them the answers they were seeking.

I’m in awe of the astronomer in each of those cultures who kept looking and looking at the records until, in an astounding flash of brilliance, that scientist discovered a rhythm in the eclipses, providing that culture with the ability to see into the future.

Terry Ward is freelance writer based in Tampa, Florida.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com