Drunken Driver Who Killed Boy Scout Gets Maximum Sentence

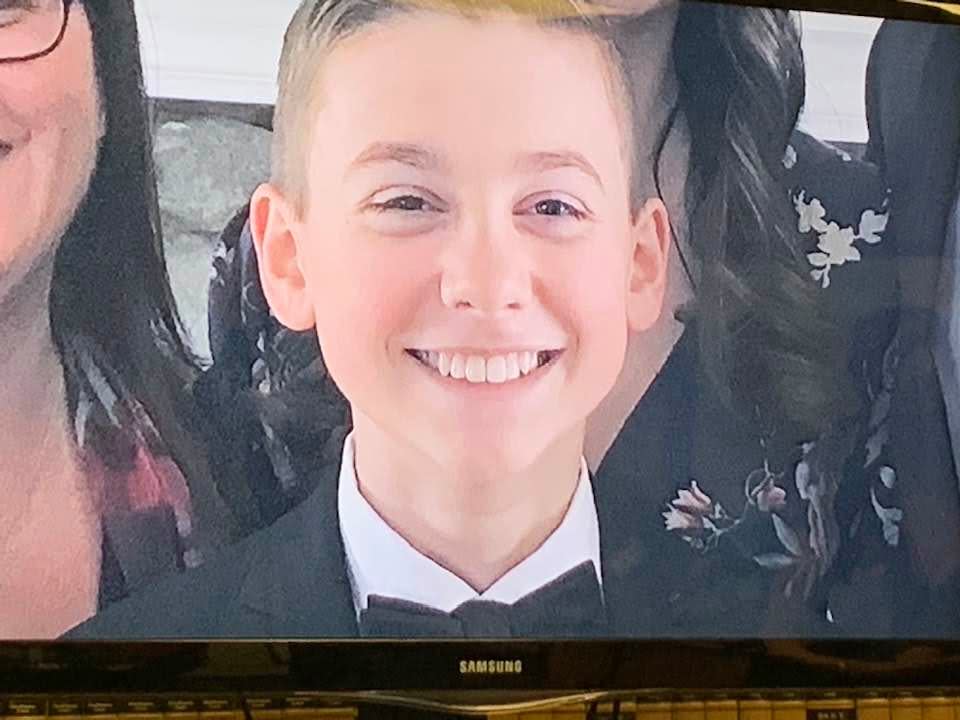

RIVERHEAD, NY — Exactly two years to the day that Andrew McMorris, 12, was killed by a drunk driver who plowed into his Boy Scout troop while they were out on a hike in Manorville, justice was served: Thomas Murphy, 61, of Holbrook, who was convicted by a jury of driving drunk and killing Andrew in the 2018 crash, received the maximum sentence of eight and one-third to 25 years in prison.

The day was marked by tears and intense grief as members of Andrew's family, who live in Wading River, spoke about the last hours of his life, about feeling his hands grow cold and washing their boy before placing him in a body bag, then planning his funeral and burying their only son and brother.

The sentencing came after Acting Suffolk County Supreme Court Justice Fernando Camacho denied a motion filed by Steven Politi, Murphy's defense attorney.

Politi had delayed sentencing, alleging jury misconduct and "new evidence." Camacho denied the motion because the jurors all said they "were in no way influenced" by outside sources.

On Sept. 30, 2018, shortly before 2 p.m., Murphy was leaving Swan Lake Golf Club to drive home after drinking alcohol since about 9 a.m., Suffolk County District Attorney Tim Sini said. Murphy's vehicle struck the group of Scouts, killing Andrew, seriously injuring Thomas Lane of Shoreham, and injuring Denis Lane of Shoreham and Kaden Lynch of Calverton, Sini said.

"It was Mr. Murphy's choice to drink vodka to excess on a Sunday morning," Assistant District Attorney Ray Varuolo said on the first day of the proceedings. Andrew ricocheted off the side mirror; his small, 100-pound body was "vaulted into the air," landing facedown in the grass and dirt, Varuolo said.

"His neck and spine were severed," Varuolo said. "He was decapitated internally." Describing the scene, Varuolo described screams. "Children saw their friends being tossed around like rag dolls. John McMorris saw his 12-year-old son Andrew dying."

He added, "A little boy doesn't stand a chance against a drunk driver in an SUV."

When he got out of his white Mercedes SUV, Murphy reportedly said, "Oh, s---, I'm in trouble," Varuolo said. Murphy reportedly said "Are the boys OK?" repeatedly.

Andrew died 14 hours later at 4:07 a.m. on Oct. 1, 2018.

Murphy, or "Murph" to his friends, had played just six rounds of golf before he became more interested in drinking, Varuolo said. Videos taken with his phone show him slurring his words and professing his love for his softball buddies and men he'd grown up with; he also talked about dancing that morning at the Swan Lake Golf Club, Varuolo said. One friend was so worried he asked Murphy if he could drive him home; although he knocked on the window, Murphy refused, closing the window and locking the doors, sealing the fate of the Scouts, Varuolo said.

On Wednesday, a crowd of supporters dressed in red and waited outside the courthouse, hoping for justice for Andrew.

Murphy, wearing a gray suit, his arms around two of his grown daughters and his wife Jackie, sat inside the courtroom as Andrew's parents, sister, two grandfathers, fellow Scouts and friends read impact statements about how his death had irrevocably changed their lives.

Alisa McMorris, Andrew's mother, read an impact statement that brought the courtroom to tears.

On the last day of his life, Andrew came into her room with the dog, told her it was a beautiful day, and asked to open the window. "I remember thinking, 'His voice is changing,'" she said. He got into bed for a snuggle, she said, and suddenly, he was her little boy again. "Soon, he asked, 'Is it time to get up, Mom? Is it time?'" she said. "I've replayed that moment 1,000 times. I want to go back and say, 'No.' I want to hold him. I want to stop time at 7:46 a.m."

Later, the family went to church and then headed to the hike, where Alisa took a photo of her son by the Pine Barrens sign. The hike was a big deal, she said, and she wanted to photo for the Eagle Scout album she would one day compile.

"I didn't want to leave," she said. But the day was full; Arianna, Andrew's sister, had a Girl Scout Silver Award ceremony. "I said goodbye to my men. Then I asked Andrew if he was okay, if he needed anything, and he waved. That was the last time I saw him."

Then came the phone call. There had been an accident. Andrew was hurt, she said. "I said, 'Is he breathing?'"

Her husband told her to hurry, she said; Andrew was bleeding and his legs were broken.

She recalled the terror of rushing to pick up her daughter and try to find the site. Andrew was brought to Peconic Bay Medical Center to be stabilized and later to Stony Brook University Hospital.

But she heard the words she said no parent ever should have to hear: "He has no pulse." She screamed. "Come on, Andrew! Come on, baby! Please, Andrew!"

She should have known from the faces of the group of doctors, from the words, "We have exhausted all our options," she said. "My baby boy was brain dead."

They stayed with their boy, played his favorite music, she said. Whispering to her son, she said, "My sweet boy, I'm sorry I can't fix you."

Running into the room, streaked with his blood, Alisa said her boy was so still, he seemed to be sleeping. Later that night, his hands grew cold. "I told my husband, 'He's transitioning. We have to help him.' I told him to go be with God," she said, her voice breaking.

When her boy was gone, she told the doctors that she and John wanted to wash their son and place him carefully into the body bag. "I wanted to be the last person that touched him," she said. And then, as she had so many times, she bathed her little boy, crossed his hands, and leaned down to kiss him one more time.

She said she listened to his heart, to be sure, really certain, that he wasn't breathing before she let him go.

The nights now are filled with the unimaginable, the horror she can't escape, Alisa said, images of the crash, to a place where "no one can protect my boy." Those last moments haunt, she said. She asks the questions endlessly in her heart: "Were you scared? Did you need me? Were you suffering?"

Planning his funeral, Alisa said, she made sure to put something soft in his coffin because he loved soft fabric. Then came the unthinkable — having to lower her child in a box into the dirt.

Her son's death stole her daughter's childhood and tore apart their happy family of four forever, she said. "I now know I will never feel that joy again," she said."Every day that passes is a day without my baby."

His friends have grown taller, while Andrew is frozen in time, she said, adding his room is losing his little boy smell.

At first, Alisa said, she thought she felt sorry for Murphy, a father, a husband. "I thought, 'Why didn't someone care enough to tell you not to drive?'" Then she heard that he was offered a ride and refused; her heart dropped. "Shame on you," she said.

Politi said since the day of the crash, Murphy has led an "exemplary life," not drinking, not driving, and showing up early for every scheduled court appearance. He asked for a few days to prepare a more detailed sentencing memorandum; Camacho said Politi had time and was aware the sentencing could take place Wednesday. "This sentencing will proceed today," he said.

Politi presented Camacho with 100 letters in support of Murphy. He also said Murphy, who has health problems including coronary and lung issues and diabetes, was at a high risk for COVID-19 and asked for a two-week adjournment so he could address the appellate division; that request was not granted.

As Camacho readied to sentence Murphy, Polito read a letter from his daughter, who called him "her greatest hero," a man with a huge heart. Polito said Murphy was not an evil man, as some had said, but instead, a devoted father and husband, a charitable man who organized a fundraiser the night before the crash. He had no prior criminal record, he said. He was a coach and member of his church. "This is a man who cares," he said, stating that many times during the testimony, Murphy asked how the boys were. "To say he doesn't distorts the truth."

Listing his health concerns, Polito told Camacho that anything more than the minimum sentence for Murphy could be a "death sentence."

Murphy did not make a statement on the advice of his attorney, who said they plan to appeal.

Camacho spoke before he sentenced Murphy. He said the evidence was "absolutely overwhelming" that the boys had been walking on the side of the road, supervised, and Murphy left the road and struck them. He was "driving while intoxicated, a reckless, selfish act that took the life of this beautiful 12-year old boy," he said. "So much pain, so much suffering. People in this community are broken because of Mr. Murphy's actions."

Murphy left a trail of tears, "death, destruction, suffering and pain," Camacho said.

He added that Murphy had led a decent life and was a decent man. "The message that needs to go out is that there have to be consequences, even for decent people that cause so much pain and suffering," he said.

Murphy's wife and two daughters were visibly distraught: His daughters hugged their father before he went up to face the judge. His wife Jackie, after the sentencing, asked, "What did he get?" When she was told it was the maximum, she cried out, "This is unbelievable! I can't even give him a hug? Tom! You hang in, Tom!" She hurried out of the courtroom and collapsed on the floor beside the elevators. Her daughters said she could not breathe; she was receiving medical attention as court officers directed those present to leave the hallway.

In an emotional statement, John McMorris, Andrew's father, spoke of that Sunday that started out bright and blue, a perfect day for a Boy Scout hike after church with his son. He spoke of days at Camp Yawgoog with his boy, of Andrew inspiring him out of his comfort zone, to ride rollercoasters and plunge into icy lakes.

"He had a zest for life. I treasured the relationship I had with him," he said. "Losing Andrew was like losing my very own heart."

Andrew, he said, lived life to the fullest, was impatient on every moment wasted waiting for his family to get ready in the mornings before a day at Disney World or skiing — he wanted to use those moments making memories, his dad said. His son, he said, had a strong work ethic, was often on the Honor Roll, was excited about making his confirmation, and was determined to see his dreams come true, even writing away for college brochures about aviation at just 12 years old.

On that last day of his life, McMorris said, Andrew packed his day pack for the hike, filled with a first aid kit, bug spray and other essentials. "That should have been all he needed," he said. "There was nothing he could have done to protect himself from a drunk driver in a Mercedes SUV who plowed into him and the other Scouts."

McMorris relived the horror of what came next, of seeing his son die before him, as the brightest of days turned into the darkest of nightmares. "The images of Andrew's mangled, bloody body... holding his hand as it grew cold ... having to zip my son into a body bag," will stay burned into his mind forever, he said.

Even the chance to donate his organs was stolen from them, his parents said — Andrew's injuries were too severe.

He spoke of all the things he will never again do with his son — walks and talks and hikes and pancakes for breakfast. Graduations and confirmation, a first kiss and wedding day. The chance to see his boy realize his dreams as a pilot and grow into a fine man, an Eagle Scout.

His son, McMorris said, loved Halloween and Christmas most of all, playing Santa and being with the family he adored.

"He did not deserve what happened to him," McMorris said. "We will suffer for the rest of our lives."

To Murphy, he said: "Andrew didn't die that day. He was stolen from us. He was ripped from us ... because Mr. Murphy made the despicable and selfish choice to drive drunk. If I had to sum it up in one word: Avoidable."

And, McMorris said, the second-worst nightmare of his family's lives has been the two endless years of court dates and a trial where they were forced to relive their agony because Murphy "didn't take responsibility for his actions."

Boy Scouts, he said, have a slogan: "Do a good turn daily." He urged the judge to do the right thing and sentence Murphy to the maximum extent allowable, so his son's death would not be in vain.

Andrew's sister Arianna remembered days at Disney World, eating ice cream in the Animal Kingdom and laughing on the rides. "Andrew was an incredible little boy," she said. He was obsessed with airplanes from the day he was born and even had airplanes on his slippers, she said.

Her voice rising, she turned to Murphy. "You took my brother from me," she said. "You took my childhood — my childhood was stolen from me." She went from being a normal teenager to a girl who had to help choose clothes for her little brother to wear in his coffin and music to play at his funeral, she said. And, she said, "You stole my parents from me." Her parents, her whole family, she said, are forever changed. "I long for the days when we were truly happy, just the four of us."

Another impact statement was read by Colleen Lane, whose son Thomas Lane was seriously injured. Denis Lane was also hurt, as was fellow Scout Kaden Lynch. Lane spoke of the "ripple effect" the crash has had on the community. Her voice shaking, she spoke of her son Denis' bloody pants on the day of the crash, of the screams he heard after his brother was hit. She spoke of the battered backpack, blood-stained and scratched, that likely saved her son Thomas' life.

The memories of that day haunt, Lane said. "This will never go away for me. This didn't have to happen. It was so avoidable. The defendant's choices are the reason we are all here," she said. "I will never forget what he has done to my children. He will receive no forgiveness or sympathy from me."

Denis Lane's voice shook and he was visibly distraught as he spoke of the day two years ago when he saw his brother Thomas' "broken face," heard his screams, and found himself covered in blood, "some of which was not mine." He spoke of pain, of anger, of trying to bottle up the emotions too hard to speak about. "I beg you to understand our suffering," he said to Camacho.

Andrew's grandfathers both spoke; his paternal grandfather, Jim McMorris, shared the pain of having his son John tell him he wanted to "bring him to say goodbye to Andrew." McMorris said during those last moments, he took the hand of his young grandson, who loved aviation. "I told him he was about to go on the most exciting flight of his life," he said.

Alisa's father, William Schaefer, said losing Andrew was like "tearing a part of our bodies from us. No one in our family will ever be the same. We are broken."

Ending his statement, Schaefer looked directly at Murphy: "Shame on you," he said.

Letters from family members echoed with the words that defined Andrew's young life — caring, talented, loving and kind. A boy who loved nothing more than to fly and be a pilot for American Airlines. A young man who loved acting, music, playing instruments, dancing like Michael Jackson and creating art. An adventurer who loved to hike, swim, play sports. The life of every family party who brought smiles of delight when he burst in saying, "I'm here." So many who spoke said, "He was my best friend."

His friends said how much he would have loved the last show they did at school, "The Wiz." How much they miss him and don't understand why he won't be there for all the big moments, for high school graduation.

"A piece of me has died," one friend wrote.

Another friend remembered the talent show where he and Andrew played the drums and performed "Smoke on the Water," by Deep Purple. "I've stopped playing the drum now," he wrote. "I'm broken."

After the sentencing Arianna McMorris spoke about her brother's loss: "There are no winners today. Andrew did not come back to life. Thomas and the other Boy Scouts did not recover from their injuries. And Thomas Murphy is going to prison and getting his earthly consequences for the actions and wrongdoings he committed."

A video montage for Andrew was shown, as his favorite song, "Somewhere Over the Rainbow," played.

"Today there are no winners. We are all broken," Alisa McMorris said. "We hope today's decision is a deterrent so this will never happen to another family. Two years is too long — but it's done."

On Wednesday night, a virtual gala was held to celebrate Andrew's life and benefit the Andrew McMorris Foundation so that his legacy can live on.

"Today, justice was served,” Sini said. “Not only did the families and their supporters stay strong and resolute throughout this process — trusting that justice and the truth would ultimately prevail — but they also managed to turn their grief and their loss into something positive, becoming advocates in the community for safe driving and trying to prevent a tragedy like this from ever happening again. While nothing can bring Andrew back, I urge the people of Suffolk County to honor his memory by vowing to never make that selfish, reckless decision to drive drunk. Let that be his legacy: that no other family should ever have to go through this tragedy.”

Murphy was convicted by a jury on Dec. 18, 2019, of aggravated vehicular homicide, a felony; second-degree manslaughter, a felony; second-degree assault, a violent felony; second-degree vehicular assault, a felony; two counts of third-degree assault, a misdemeanor; and reckless driving, a misdemeanor.

This article originally appeared on the Riverhead Patch