Druw Jones part of a growing class of next-gen MLB stars with last-gen bloodlines

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Pull up to Dodger Stadium on Tuesday and you’ll watch the best baseball players in the world on the same field for Major League Baseball’s All-Star Game. Shohei Ohtani. Aaron Judge. Mookie Betts. Mike Trout.

Pull up to an All-Star Game in 20 years and there’s a good chance you’ll watch one of their sons in uniform.

Every year, the offspring of former pro athletes are reaching the highest level in their respective sports, seemingly at an increasing rate. The trend might be most prevalent in baseball. On Sunday, another batch of second-generation players will hear their names called during MLB’s draft.

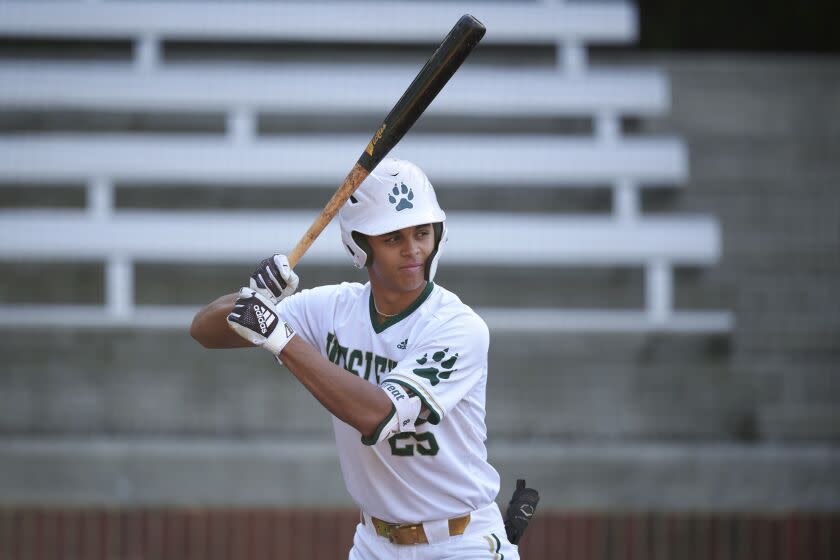

Druw Jones, the son of former Dodgers outfielder Andruw Jones, is widely considered the best prospect available. If it’s not him, then it might be Jackson Holliday, the son of former All-Star Matt Holliday. Next on the list might be Cam Collier, the son of former major leaguer Lou Collier.

Sandwiched in that group atop mock drafts? Elijah Green, the son of former NFL player Eric Green. A little later in the first round you’ll find Justin Crawford, former Dodgers outfielder Carl Crawford’s son.

“I've noticed it too,” Tony Gwynn Jr. said. “There are a lot more players.”

Druw Jones was 4 years old when his father, who made his major-league debut at 19, left the Atlanta Braves to sign with the Dodgers after the 2007 season. Druw's mom, Nicole Jones, said he was already on a baseball team in Georgia by then, but his parents didn’t force the sport on him. No, she said, it was because Druw showed interest on his own.

“Before he could talk, he held a water bottle by the neck, swaying it around, like he was getting ready to hit,” Nicole Jones said. “He put ping-pong balls on bottles to hit off like a tee. He had a pacifier and a diaper on. He would scoot down the way and do it himself.”

Nicole and her father guided Druw’s burgeoning baseball career while his father was away playing in the majors. He remained at the same school in Georgia from kindergarten through high school. He has committed to play at Vanderbilt but is expected to sign with the team that drafts him Sunday, joining his father as a professional. The Baltimore Orioles hold the No. 1 pick, followed by the Arizona Diamondbacks.

He'll join Gwynn Jr. as one of the most famous second-generation examples. Gwynn Jr.’s father was a first-ballot Hall of Famer for the San Diego Padres. His uncle, Chris, reached the majors, too. He grew up going to his father’s every day once the school year was over — but only when he was old enough to catch a big-league flyball.

“My dad was pretty serious about if I was going to come to the field with him,” Gwynn Jr. said. “I needed to understand that, although it was a game to me, it was a job and a livelihood for all these men. And I needed to be able to protect myself.”

Gwynn Jr. said he doesn’t remember missing a day at the ballpark those summers. He took groundballs. He took hacks. When he was old — and brave — enough, he picked players’ brains.

“I'm a big believer of seeing it allows you to dream it,” Gwynn Jr. said.

Gwynn Jr. said he believes the exposure propelled his career. The Brewers drafted him in the second round of the 2003 draft. He made his major -league debut three years later. He spent parts of eight seasons, including two with the Dodgers, before moving on to a broadcasting career in San Diego.

The Gwynns weren’t the first multi-generational big-league family. The Boones and Hairstons had three generations reach the majors. Ken Griffey Jr. famously broke into the majors as his father’s teammate in 1990. Jose Cruz Sr. and Jr. each enjoyed long careers. Cal Ripken Sr. managed his sons, Cal Jr. and Billy, in Baltimore.

Examples are scattered around the majors today. Padres shortstop Fernando Tatis Jr.’s father once hit two grand slams in one inning at Dodger Stadium. Dodgers outfielder Cody Bellinger’s father, Clay, played parts of four seasons in the majors and has three World Series rings. On Saturday, Darren Baker played for the National League in the Futures Game. His father, Dusty, will manage the American League in Tuesday’s All-Star Game.

One of Baker’s players will be Toronto Blue Jays first baseman Vladimir Guerrero Jr. His father was a nine-time All-Star and Hall of Famer. Dodgers third base coach Dino Ebel knows. He was on the Angels’ coaching staff for Vlad Sr.’s five seasons in Anaheim. And when Vlad Sr. won the Home Run Derby in 2007, Ebel was his pitcher. An 8-year-old Vlad Jr. was there.

“I used to hit him groundballs and flyballs,” Ebel said. “Now he’s a superstar.”

Ebel, who reached double A as a player, now has two baseball-playing sons of his own aspiring to reach the pinnacle. His oldest, Brady, just finished his freshman year at Etiwanda High and is already being recruited by some of the top college baseball programs in the country.

Ebel’s sons are familiar faces at Dodger Stadium. They hit in the batting cage. They field groundballs. They learn the right techniques and how to process vital information.

“The bad part of it is the pressure,” Ebel said. “I know I never played in the big leagues, but it's my 17th year as a coach in the major leagues. There's a lot of chatter like, 'Your dad's in the big leagues' or they get first opportunity because of this and that.”

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts said his son Cole, an infielder at Loyola Marymount, faced similar scrutiny growing up in San Diego.

“It's tough,” Roberts said. “And having to follow in someone's footsteps is difficult. So, my thing for me is I just want my son to find whatever he has passion about and love and be who he is.”

Dodgers outfielder Trayce Thompson said his experience was different. His father, Mychal, was the No. 1 pick in the 1978 NBA draft and spent 13 seasons in the league, including five with the Lakers before he retired the year Trayce was born.

“He just kind of let us choose whatever we wanted to do, whatever we loved, and for me it was baseball,” Thompson said of his father, who is now a Lakers television analyst.

Thompson’s older brothers, Klay and Mychel, went the basketball route. Mychel reached the G -League. Klay is a five-time NBA All-Star and four-time champion. He was one of five players in June’s NBA Finals whose fathers played in the NBA, alongside Stephen Curry, Andrew Wiggins, Gary Payton II and Al Horford.

“I think it's just by osmosis, right?” Thompson said. “You just grow up kind of expecting it to happen even if the odds are kind of stacked against you. I mean, look at Steph. Steph is not some physical freak. And obviously he's gifted. The best ever to do it. But as far as the physical tools, he was very looked past and wasn't a high recruit. My brother wasn't a high recruit. But I think it's huge, just kind of mentally, comfort wise.”

Last month’s NBA draft featured several second-generation picks. This month, Shareef O’Neal and Scotty Pippen Jr. played for the Lakers' NBA Summer League team after going undrafted, attempting to create their own path from the bottom rung. Next year, Bronny James, LeBron’s oldest son, will be eligible for the draft.

On Sunday, some second-generation baseball prospects will receive their chance. Soon enough, you might see them in an All-Star Game, too.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.