Dry wells, muddy water: Extreme reservoir drops tax Oregon drinking water, tourism

This story was updated at 10 a.m. Tuesday

Larry Nelson was taking a shower this fall when his water abruptly stopped.

“I knew what happened right away — my well had gone dry,” said the 74-year-old Vietnam veteran, who lives east of Lowell along Lookout Point Reservoir. “The same thing had just happened to my neighbor.”

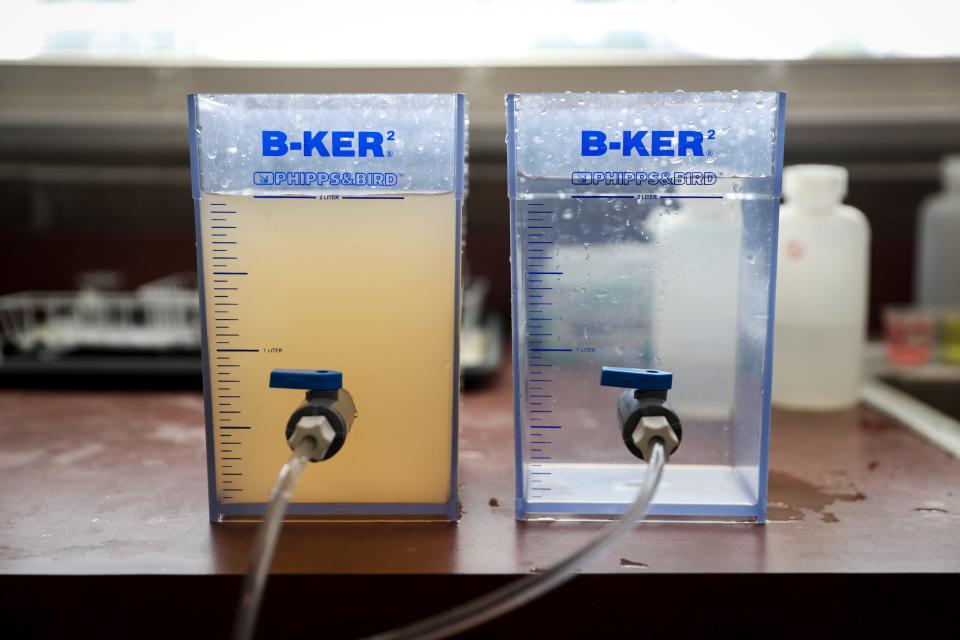

Roughly 33 miles to the north, Greg Springman, public works director for the city of Sweet Home, also is struggling with water. The city’s drinking water source at Foster Reservoir has turned the color of chocolate milk, often filled with over 14 times as much sediment as normal.

“Our team has been working through the night — all hands on deck,” Springman said. “Normally we have the purest, best-tasting drinking water in the state. Now we’re working around the clock just to keep it within state parameters.”

Both problems, Nelson’s dry well and Springman’s muddy water, are coming from the same source: a court-ordered extreme drawdown of Lookout Point and Green Peter reservoirs meant to save endangered salmon.

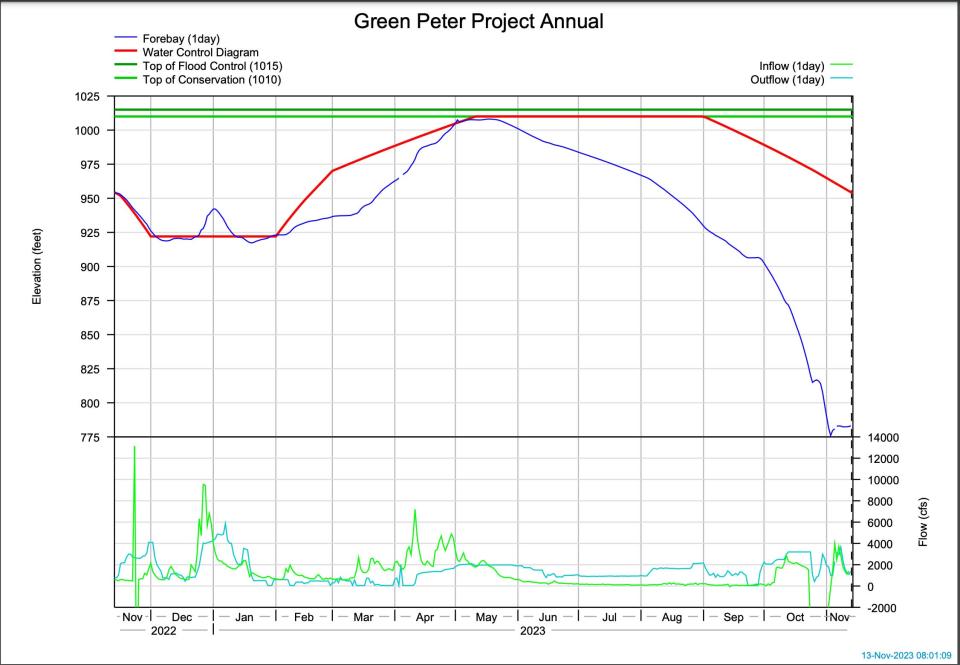

The drawdowns, executed for the first time since a court order, gradually dropped reservoir levels throughout summer but plummeted to historically low territory by August at Lookout Point and October at Green Peter.

As the reservoirs transformed back into rivers, the water is flushing mass amounts of built-up sediment downstream into the South Santiam, Middle Fork Willamette and mainstem Willamette rivers. That’s hammered drinking water systems of downstream cities such as Sweet Home, Lebanon and Lowell, and to a lesser extent, Albany.

The cities have had to use additional chemicals, such as chlorine and sodium hypochlorite, while taxing their filters, to keep water within state parameters. It has led to a discolored and sometimes odd-smelling water. In Lebanon, public works officials said they may need to replace all their filters — a $4 million expense — because of how much sediment is in the water coming from the South Santiam.

The Army Corps anticipated muddy water being an issue during the drawdowns — and said they warned cities in advance. However, "I don't think there was real understanding about the magnitude and duration of the turbidity (muddy water)," said Greg Taylor, supervisory fish biologist for the Corps in the Willamette Valley.

Corps surprised at wells drying up

The Corps said the drying up of wells came as a surprise.

"We did our best to identify potential impacts that could result from the operational changes in the court’s injunction measures, however, not all potential impacts were studied or known at the time," Corps spokesman Jeffrey Henon said.

Nelson said he knew of four people who live along Lookout Point Reservoir who’ve had their wells dry up. He said their wells worked at the reservoir’s normal low-water level of 850 feet above sea level. But once it dropped below 830 feet, the wells went dry. Lookout Point will be brought all the way down to 750 feet.

Nelson estimates he’ll pay $25,000 to $30,000 to drill and set up a new well deep enough for the new reality.

“I’m a pretty easygoing guy, but this situation has got me upset,” Nelson said. “I can’t believe they’re going to wipe everything out in this experiment to save fish. I want to save the fish, but at what cost? Right now I’m just a disabled veteran trying to get his water back.”

Why the drawdowns?

In response to a lawsuit from three environmental groups, U.S. District Judge Marco Hernandez ordered U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 2021 to undertake a series of actions meant to prevent the extinction of Upper Willamette River wild spring Chinook salmon and winter steelhead.

One of those actions was dropping Green Peter and Lookout Point to the lowest levels since the dams were built. The drawdowns are planned to occur each year into the foreseeable future.

The Army Corps is using trucks to move adult salmon above the dams, into high-quality spawning habitat of streams such as Quartzville Creek and the upper Middle Fork Willamette. After the adults spawn, juvenile fish swim downstream. Historically, when they hit the reservoir, they have struggled to continue through the dams because of the reservoir depth.

Willamette Valley dams are too high for classic fish ladders. Fish collection devices that move the fish downstream have been considered, but they’re very expensive. For now, the best option is for fish to migrate out through gates or outlets low in the dams, environmentalists and Corps officials said.

That means dropping the water way, way down.

“Fish are surface oriented, meaning they live in the top 20 to 50 feet of the water column and they just don’t find those gates unless they’re closer to them,” Taylor said.

How long will muddy water have impact?

The muddy water coming out of the reservoirs is sediment built up over decades. The reservoirs will drop to their lowest levels since being constructed in the 1950s and 60s.

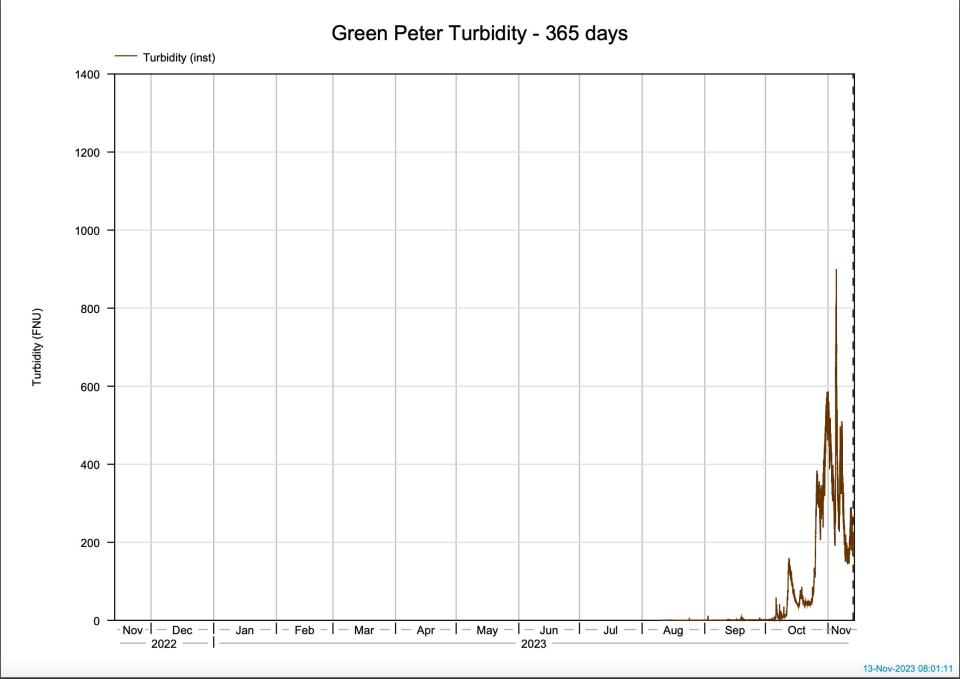

The muddy water started in late August at Lookout Point and early October in Green Peter and Foster reservoir area, Taylor said. It’s likely to continue through at least Dec. 16 when the Corps will start refilling the reservoirs.

Taylor said he expected muddy water to be an issue in coming years, but that it should eventually ease somewhat as sediment trapped for decades is flushed downstream.

“The reality is that this is going to be an issue going forward,” Taylor said. “We should see less of it over time but it’s hard to predict how it’s going to play out.”

How muddy is that water?

The level of turbidity — sediment in the water — has been off the charts since the drawdowns.

In Foster Lake and the South Santiam, the water is normally clear and turbidity measures below 20 formazin nephelometric units (FNUs). During heavy rainstorms, it can get as high as 40 to 60 FNUs. This month, both have been between 200 to 300 FNUs. In Green Peter Reservoir, turbidity has reached almost 600 FNUs.

The same is largely true at Lookout Point where turbidity has climbed to between 200 and 400 FNUs while the Middle Fork Willamette is running 100 to 200 FNUs.

Muddy water leads to struggling systems

The sediment coming out of the reservoirs has meant extra work and expense for public works departments treating drinking water in cities downstream of the reservoirs.

So far, the water has remained safe to drink, although some residents have complained about the water being discolored or its smell, officials said.

In Sweet Home, Springman said impacts on the town include overtime, the cost of chemicals needed to treat the water and wear and tear on pump and filtering systems.

“I’d say it has been a major impact,” he said.

Just down the road in Lebanon, population 19,000, public works director Jason Williams said the strain on the town's water filters has him worried they may need to be replaced at a cost of $3.5 million to $4 million.

"We don't have a pre-treatment process for our water because the quality has always been so great, so now, everything that's coming in is going straight into our filters and strainers and it's plugging and fouling all the time," he said. "It requires a lot more backwashing and chemical cleaning and it's just a lot of pressure on the system.

"The concerning thing is that we have another month of this. We've never dealt with anything like this before. We're making it up as we go."

In Lowell, population 1,200, officials said once the turbid water started arriving, they worked overtime, upping the amount of chlorine in the water to ensure it was safe. That led to water that was discolored and had a "slight chlorine smell."

They’ve since fine-tuned the treatment process to return the water closer to what’s normal, city administrator Jeremy Caudle said.

“This is having an impact on our budget in terms of increases to staff time and chemicals. I cannot yet quantify those impacts,” Caudle said in an email. The workload has returned closer to normal, he said, as the city is "evaluating potential new treatment processes in case turbidity continues to increase so that they can remove sediment more efficiently.”

Decline in fishing, tourism

Taylor and Springman said some of the loudest complaints about the muddy water have come from a decline in tourism, as anglers haven’t been able to fish the reservoirs or downstream rivers.

Autumn is a popular time to fish, but the extremely muddy water makes that basically impossible.

“Normally we have tons of boats out there, but at this point we’re not seeing any recreation at all,” Springman said.

“That’s a major impact not only for Sweet Home but other towns nearby," he said. "It’s a big reason people visit and spend money in our community, and it’s just not happening now.”

Fish kill remains source of frustration

As the Statesman Journal previously reported, the drawdowns at Green Peter caused tens of thousands of kokanee salmon to die of “barotrauma and gas bubbles in their bloodstream and body cavity."

The cause was being sucked from very deep in Green Peter Reservoir, through a regulating outlet in the dam to essentially the surface of the water downstream, Taylor said.

The rapid move from deep to shallow water caused the fish's swim bladders to rapidly inflate and kill them in droves.

Does muddy water impact fish?

Taylor said the Corps has studied whether the highly turbid water being released from the reservoirs can impact fish already in the system in other ways.

“We don’t see mortality, but we have seen the gills of resident fish being irritated after prolonged exposure,” Taylor said. “A lot of fish also feed visually, so it’s not unusual to see impacts on condition of fish as they’re not feeding as effectively.”

Taylor stressed that for juvenile spring chinook — the fish these drawdowns are meant to help — the drawdown means a lot more of them can move downstream far quicker and more effectively.

“In the past there was no effective way out and mortality was really high. This is better when we’re talking about spring chinook," Taylor said. "We’re seeing early signs more fish are already getting out and downstream. And it happens fast enough that I don’t think they’re being impacted by the turbid water.”

Environmental groups that sued defend drawdowns

Mark Sherwood, executive director of the Native Fish Society, one of the groups that filed the lawsuit, defended the drawdowns as a critical step for saving wild salmon in the Upper Willamette.

“The Army Corps have done nothing for wild spring chinook, and if we would have continued to do nothing, they were going to go extinct,” Sherwood said.

He suggested the Corps should make grants or funding available to those with wells and downstream cities that have been impacted.

“Losing a well was not anticipated and really painful. I understand that,” Sherwood said. “The Army Corps should work with those folks and compensate them for drilling deeper wells.”

The drawdowns were simply the most effective and inexpensive way to save salmon, he said. Since the dams won’t be removed, the options are between the drawdowns or building expensive fish collectors at the dams.

“Big picture, the alternative plans from the Corps that keep the reservoirs full are vastly more expensive and don’t work,” Sherwood said.

Corps won’t compensate cities or owners

A Corps spokesperson said the agency doesn't have the authority to “compensate private landowners or local governments for well drilling or municipal water supply.”

“The Corps can only spend appropriated funds for purposes authorized by Congress,” spokesperson Henon said.

“As we learn more about the impacts these operational changes have, we will see where we can make improvements while complying with the court’s Injunction measures,” he said.

Zach Urness has been an outdoors reporter in Oregon for 15 years and is host of the Explore Oregon Podcast. To support his work, subscribe to the Statesman Journal. He can be reached at zurness@StatesmanJournal.com or (503) 399-6801. Find him on Twitter at @ZachsORoutdoors.

This article originally appeared on Salem Statesman Journal: Extreme reservoir drops tax Oregon drinking water, tourism