Dual language classes are growing in Arizona schools. Tom Horne says they violate the law

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

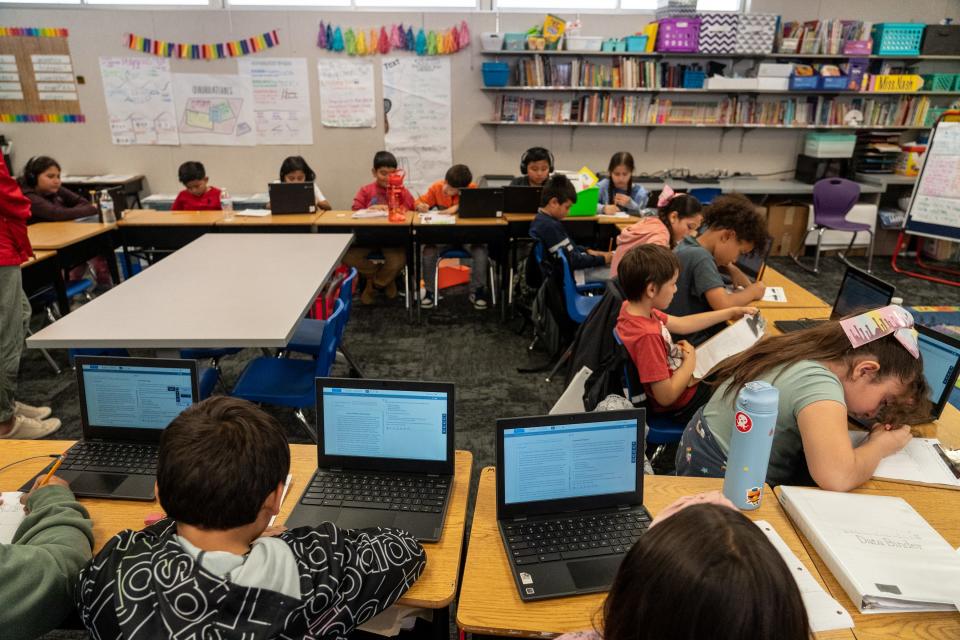

Teacher Gwendolyne Darony asked her third graders to recite four basic language skills. But instead of English, Darony asked in Spanish.

"Escuchar. Hablar. Leer. Escribir," the students responded in sing-songy unison. Listen. Speak. Read. Write.

For the rest of the morning, Darony spoke to her students only in Spanish. The walls of her classroom were also filled with words and phrases written only in Spanish.

Meanwhile, in the classroom next door, teacher Nicolle Nash helped students write essays. In contrast to Darony, Nash spoke only in English. All of the words and phrases in her classroom were written in English.

Welcome to the third grade dual language classroom at William C. Jack Elementary School in Glendale. Students spend 50% of the day receiving all their academic instruction in English and 50% in Spanish. After lunch, Darony and Nash's students trade classrooms.

The K-8 school is pioneering a dual language program that already extends through fourth grade. Next year it will expand to fifth and eventually through eighth.

Dual language programs are growing in number in Arizona after the state passed a law in 2019 to counter the effects of Proposition 203, the state's English-only immersion education law. The 2019 law gives school districts more flexibility to teach English learners, including through dual language programs.

But the programs face a threat from Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne, who maintains they violate Proposition 203. He could try to bar English learners from participating in dual language programs.

Proposition 203 was a ballot initiative passed by voters in 2000. It curtailed bilingual education in Arizona for most students not proficient in English by requiring them to be taught only in English immersion language acquisition programs rather than bilingual and other programs that teach students in more than one language.

Years of mounting data convinced lawmakers in 2019 that English learners were not succeeding academically under Proposition 203.

Public schools are required to provide students classified as English learners equal access to programs and services under the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the 1974 Equal Educational Opportunities Act. Arizona is the only state in the nation that still has an English-only immersion law on the books. It can only be repealed through another ballot initiative, and legislative attempts to send a repeal initiative back to voters have failed. So lawmakers decided to revamp its administration instead.

The 2019 law gives schools more flexibility to teach the state's 93,000 English learners, who make up about 8.5% of all Arizona students.

It reduced the minimum number of daily hours English learners are required to receive English-only instruction for English language development from four to two. It also opened the door for schools to teach English learners through 50-50 dual language programs. The pandemic delayed some schools from implementing some of the changes. But now dual language programs are quickly gaining steam.

At least 110 schools in Arizona offered dual language programs during the 2021-22 school year, 30 more than the previous year, according to Arizona Department of Education data. There were 941 students in Arizona enrolled in dual language programs last year, about 200 more than the year before. Data for this year has not been publicly released. But it is expected to show more increases.

The number of students enrolled in dual language programs, however, remains just a sliver of the state's English learners. Most of them are still being taught in English immersion programs, data shows.

What is a dual language program?

Many educators see dual language programs as a positive alternative to English immersion, which has been the mainstay in Arizona for teaching students not proficient in English for more than two decades under Proposition 203.

Sidar Alvarado, from Costa Rica, enrolled his 8-year-old daughter, Kamala, in the second-grade dual language program at William C. Jack Elementary School this year. He wants his daughter to learn English.

"The reason we brought her to this country is because we want her to improve her English skills," Alvarado said. "If you want to go into corporations, companies or whatever (inside) or outside of the United States, you have to speak English."

But he was afraid his daughter would fall behind academically in an English immersion class. He also was afraid she would lose her native language, Spanish, and be unable to communicate later in life with Spanish-speaking relatives.

"If you speak two languages, you have more chances everywhere because companies want to hire people with different kinds of skills," said Alvarado, who also teaches at the school.

Dual language classrooms are made up of a mixture of students. Some are "English Learners," students whose primary language at home is not English and who are not yet proficient in English. Others are fluent English speakers. The goal is for both sets of students to become bilingual, with the ability to listen, speak, read and write in English and another language, most commonly Spanish.

The idea is that the students will learn English and Spanish from their teachers and peers while keeping up with the same academic content students are required to learn in traditional classrooms.

Under dual language programs, English learners are not segregated from English-speaking students as they are in English immersion programs. Therefore they don't miss out on academic content while learning English, proponents say.

Dual language programs also treat Spanish — and the languages and cultures of other immigrant groups — as assets to preserve, not a deficit to erase, supporters say.

"That is an incredible asset to the community. We can create global citizens that can be globally competitive because their native language is nurtured, but they're also learning English well while they are here," said Stephanie Parra, executive director of ALL in Education, an advocacy group that supports dual language programs.

At the same time, dual language programs allow English-speaking students to learn a second language, making them more competitive in an increasingly bilingual world.

"Someone that's bilingual, you can have a lot more opportunities in life," said parent Lauren Staten, whose 6-year-old son, Mack, is in the first grade dual language class at William C. Jack School.

While English and Spanish dual language programs are the most common, some districts offer other combinations. The Chandler Unified School District offers dual language programs in Mandarin Chinese.

"A dual language program can be so successful because if we allow" students who speak Spanish to learn together with students who speak English, "they both are equal partners at the table. Both of their languages are being honored and valued, and their cultures are being honored and valued," said Norma Jauregui, an assistant superintendent for the Glendale Elementary School District.

"Then the students view that as, 'Oh, I don't have deficits. I have strengths because you need to learn my language, too, and I need to learn your language. So it just helps them so much," Jauregui said.

English learners in dual language programs learn English faster than their peers in English immersion programs, according to data provided by Glendale school officials.

Students who already speak English in dual language programs also score higher on reading and math proficiency tests than students in regular classrooms.

"Research shows that when students are learning a second language, they are basically lighting up a part of their brain that would not normally light up," said Alejandrina Garcia, director of language acquisition at the Glendale Elementary School District. "It's the same section of your brain that helps with problem-solving, with multitasking and things like that. So something is happening in those students' brains ... that is making them smarter or better problem solvers."

Return of Tom Horne, a staunch English immersion advocate

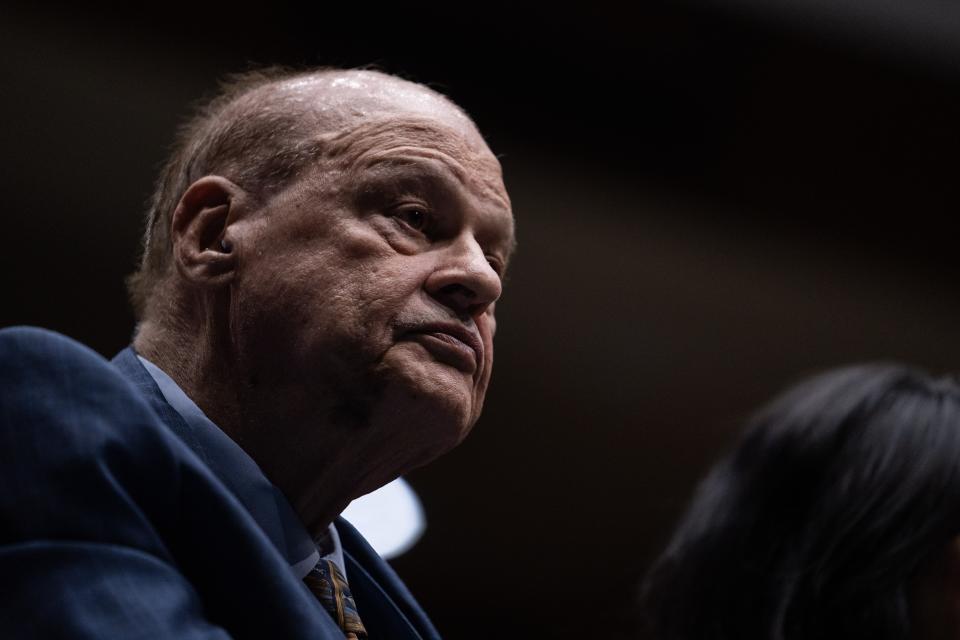

Dual language programs, however, are in danger under Horne. The 78-year-old is a staunch English-only immersion advocate. He was elected superintendent of public instruction in November after campaigning to preserve English immersion instruction.

Horne also held the position from 2003 to 2011, when he strictly enforced Proposition 203. During this earlier tenure, Horne introduced the requirement that English learners be pulled out of regular classrooms for four consecutive hours a day to receive English language instruction. He also sent representatives to school districts to ensure schools complied with Proposition 203. Some teachers derisively dubbed them the "English-only police."

Educators became fearful of speaking a single word in Spanish to English learner students in classrooms and packed away books written in Spanish.

"Teachers and administrators were afraid of being fined or reprimanded publicly," recalled former teacher Monica Martinez, who taught English learners at two Peoria Unified School District schools from 2006 to 2013.

Horne maintains that dual language programs violate Proposition 203 if they include students not yet proficient in English, typically determined through testing.

"It's not consistent with the (Proposition 203) initiative, and the 2019 law did not purport to contradict the initiative," Horne said.

The department has consulted with the Arizona Attorney General's Office to determine if the 50-50 dual language model violates Proposition 203, Deputy Associate Superintendent Adela Santa Cruz announced during an early May meeting with English learner teachers and administrators. Santa Cruz oversees the department's Office of English Language Acquisition Services.

"We are checking to see if the 50-50 dual language immersion model ... if it comports with the law," Santa Cruz said. "As soon as we do get that guidance ... you all will be the first to know because I do know that there are several (schools) and districts out there that do use that particular model."

Arizona attorney general spokesman Richie Taylor said he could not comment due to attorney-client privilege.

Horne says he supports bilingualism. But he considers dual language programs a form of bilingual education, which he vehemently opposes and says remains banned for English learners under Proposition 203.

Bilingual education, he maintains, prevents immigrant children from mastering English, which is essential to succeed in the U.S.

"Not to expect them to learn English and achieve is a kind of racism, really," Horne said.

Under Proposition 203, which remains in effect, English learners can only be taught in English, Horne said.

Under Horne's interpretation, the 2019 law permits English learners to participate in dual language programs to satisfy the two-hour English immersion requirement. But English learners can't stay in a dual language classroom when lessons are being taught in Spanish or some other language, he said.

"So if they want to do that, they can. But the rest of the day, then the (English learners) have to be mainstreamed with the English-speaking kids. They can't be in a bilingual class if it's taught in Spanish or any language other than English. That's my interpretation of the 2019 statute and the initiative," Horne said.

Horne refused to say if he plans to try and shut down any dual language programs.

"Whether I exercise any sort of prosecutorial discretion, I'm not commenting on," Horne said.

Supporters of dual language programs say they will pursue sanctions, lawsuits or a recall if Horne tries to close any dual language programs.

"There are different ways to approach this. We're exploring them, and I know we're not alone," said Rebecca Gau, executive director of Stand for Children, an advocacy organization that supports repealing Proposition 203 and pushed for the 2019 reforms.

Efforts to reform English-only immersion instruction supported by research

Years of data showing English learners were not succeeding academically prompted lawmakers to pass the 2019 reforms after efforts to repeal Proposition 203 were unsuccessful, said Paul Boyer, a teacher and former Republican lawmaker. He was a House member when he spearheaded the reform legislation.

Boyer pointed out the 2019 legislation passed with unanimous bipartisan support in both legislative chambers, a repudiation of Horne's top-down, one-size-fits-all, four-hour English-only immersion model under Proposition 203.

"These students weren't learning math, science, history, everything else," Boyer said. "Not only were they not learning English, they were falling behind in every other subject as well."

The 2019 legislation decreased the time English learners were required to be pulled out of regular classrooms to learn only English from four to two hours. The law also directed the State Board of Education to adopt alternative English instruction models "based on evidence and research."

The board approved four new models for schools to teach English learners. Three are English immersion models and depend on how much English the student knows. The fourth is a 50-50 dual language model, where students are taught half the day in English and half the day in a second language.

California and Massachusetts adopted English-only immersion laws around the same time as Arizona, but the laws in those states were later repealed. Most other states leave it up to schools to choose educationally sound programs to educate English learners.

English learners in Arizona lag far behind those in other states. The graduation rate for English learners in Arizona ranks lowest of all states. About 32% of English learners in Arizona graduated from high school within four years, compared to at least 60% nationwide, according to U.S. Department of Education data for 2015-2016.

Data also shows that English learners in Arizona continuously score the lowest of any demographic group year after year on standardized tests. Less than 2% of English learners in Arizona passed standardized reading and math tests in the 2020-21 school year, data shows.

Academic studies also have concluded that students previously enrolled in English immersion instruction fell further behind academically later in school compared to fluent English speakers.

"What we found is their achievement begins to deteriorate over time," said Kate Mahoney, an education professor at the State University of New York, Fredonia, who co-authored a study of Proposition 203 published in 2022. As a result, the achievement gap expands as students age, she said.

Arizona's English-only law also has been criticized for segregating English learners from English-speaking peers for a large chunk of the school day while they receive English-only immersion instruction, causing them to miss out on other academic subjects and limiting their interaction with English-speaking students.

"There have been so many studies, I mean so many studies, that support bilingual approaches, not English-only," said Francesca Lopez, an education professor at Pennsylvania State University who previously taught at the University of Arizona and has studied the effectiveness of English-only immersion in Arizona under Proposition 203.

"It's almost as if everything that they decided to do was in direct contrast to what research says," Lopez said of Horne's earlier tenure as Arizona's top education official. "Segregating students with similar language proficiency is akin to wanting students, or any human being, to learn language in a vacuum, and that's not how we learn language."

The bully pulpit or the hammer?

Nevertheless, as superintendent, Horne is doubling down on English immersion.

He points to a single 2002 article in the journal EducationNext as evidence that English immersion is more effective than bilingual education. That article concludes that bilingualism has benefits but that English learners have better long-term outcomes when they learn English quickly in an immersion setting.

"Social concerns also play a prominent role in support for English immersion programs, as many opponents of bilingual education worry not just about its academic impact but also that it could lead to the fracturing of American society along ethnic lines," the article posits.

Horne plans to reintroduce English immersion training before the next school year to instruct teachers on how to effectively follow Proposition 203. The training is being developed by two English-only immersion proponents who led the same training when Horne was superintendent in the 2000s: Associate Superintendent Margaret Garcia Dugan and Santa Cruz, the deputy associate superintendent who oversees the department's Office of English Language Acquisition Services.

Horne said the rate of English learners who mastered English increased from 4% to 29% when he was superintendent in the 2000s as a result of the English immersion teacher training he implemented. The rate has since fallen to 9%, he said. Horne blames the decline on his successors at the Department of Education, who he says did not follow through with the English immersion teaching training he started.

John Huppenthal, a Republican who was superintendent of public instruction from 2011 to 2015 and succeeded Horne, praised Horne for rehiring Garcia Dugan to reinstitute the English-only immersion teacher training.

"She knows good policy, she knows effective results, and I think she's correct — an immersion approach works best," Huppenthal said.

But Huppenthal cautioned against trying to shut down dual language programs.

"You want to use the hammer as the last resort," Huppenthal said.

Horne's strongest weapon may be the "bully pulpit," Huppenthal said.

It's unlikely Horne has the power to withhold funds from school districts that continue to implement dual language programs against his will, said Kathy Hoffman, who was superintendent of public instruction from 2019 to 2023 and narrowly lost to Horne in the November 2022 election.

Withholding funds from those districts would most likely lead to lawsuits, she said.

Hoffman, a speech-language pathologist who speaks Japanese and Spanish, is a supporter of dual language and bilingual education programs.

"The cognitive advantages associated with being bilingual are well documented, as well as the academic outcomes for students who are bilingual. And even the economic needs ... for our children to speak more than one language, especially in Arizona," Hoffman said.

She believes Proposition 203 should be repealed.

"It's disappointing now to have to still have Prop. 203 to contend with, and I would continue to encourage our state Legislature to take a hard look at this and the research and ensuring that Arizona schools have every tool in the toolbox to serve multilingual and English learning students," Hoffman said.

In an elementary class, students help students

Back at William C. Jack Elementary School, teacher Mireya Munoz had just finished strumming a song on her guitar in Spanish to the students in her first grade dual language class.

About 80% of the 800 students at William C. Jack are Latino, including almost all of the students in Munoz's dual language class.

Not all of the Latino students in her class speak Spanish at home. Some are already fluent in English, but their parents want them also to learn Spanish. In addition to speaking, reading and writing, Munoz tries to expose her students to Spanish-language culture, hence the song in Spanish. That morning she also gave a lesson on Cesar Chavez, the Latino civil rights leader who was born in Arizona.

Dual language programs are not just about teaching students to be bilingual, she said, but bicultural as well.

With bright red hair, Mack Staten stood out as one of the few non-Latino students in Munoz's class.

No one in Staten's family speaks Spanish. But the boy has already learned a lot of Spanish in his first year in the dual language program.

Munoz asked Mack his age in Spanish, "¿Cuántos años tienes?"

"Seis," the boy answered without hesitation.

Lauren Staten, Mack's mother, said she lives outside the boundaries of William C. Jack School. She has to drive him to school each day so he can participate in the school's dual language program, which is not offered at her home school within the Glendale Elementary School District. She learned about the program from a school flier. She plans to enroll her three younger children in the dual language program when they enter school.

"Being introduced to a different language and being around kids that aren't from his same culture, I just think that that's the real world," Staten said. "We're in a new modern world where everyone around you is speaking Spanish. So I feel like now it's up to us that we're born English speakers to catch up with the times and learn Spanish, too. And honestly, I really wish I had."

Staten said her son is thriving in the program.

"He's doing really well," Staten said. "His teacher just says he's like a sponge. He just picked up on it really quickly, and the accent and everything."

But she said she doesn't think the program would have the same value if the Spanish-speaking students were not involved.

"It adds a lot of value to have people Spanish speaking children in there. Kids can help each other out in both ways. Like my son could help them with English, and they could help my son with Spanish, and I don't see how it would be fair to take those students out of there," Staten said.

Daniel Gonzalez covers race, equity and opportunity. Reach the reporter at daniel.gonzalez@arizonarepublic.com or 602-444-8312. Follow him on Twitter @azdangonzalez.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Dual language classes in Arizona schools face threat from Tom Horne