'We need to cut an instrumental.' How Duane Eddy found his sound as a young Rebel Rouser

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Duane Eddy figures he was 5 or 6 the day he saw his first guitar.

"I was in the basement with my dad, cleaning up down there or something, and I saw this thing against the wall," the man who grew up to become the most successful instrumental artist in the history of rock 'n' roll recalls.

"I said, 'What's that?' He said, 'It's a guitar.' I said 'What's it do?'"

Eddy's father showed him what it did, teaching his son a few chords.

"He said, 'I used it to court your mother,'" Eddy says. "I guess they'd go on picnics or something. This was back in the '30s, so things were different. I thought, 'Well, that's neat.'"

They were living in Corning, New York, at the time. That's where Eddy was born.

For subscribers: The twang heard 'round the world started in a Phoenix junkyard. Duane Eddy tells the tale

'Oh, my son plays guitar'

In 1951, the year Eddy turned 13, the family headed west to Tucson before settling in nearby Coolidge, where the young guitarist met the man with whom he would go on to cut some of the most iconic records ever made in Arizona — a KCKY-AM DJ named Lee Hazlewood.

It was another KCKY DJ who helped Eddy get things going on in Coolidge, though.

"My dad managed the local Safeway," Eddy says. "One day in 1953, this guy came in and my dad got talking to him, found out he was a DJ at the local station and, like fathers do, said, 'Oh, my son plays guitar.'"

Eddy laughs at the memory.

"The DJ, Jim Doyle, recorded me doing a Chet Atkins song and played it on the farm hour in the early morning."

'The guy that really made things happen here': How Lee Hazlewood defined the Phoenix sound

Jimmy & Duane in 'a happening town'

Eddy was attending Coolidge High School by then. As luck would have it, Jimmy Delbridge heard his classmate on the farm report and sought him out at school.

"Jimmy came running up to me and said, 'You want to play some music at my house?' That's how we got together."

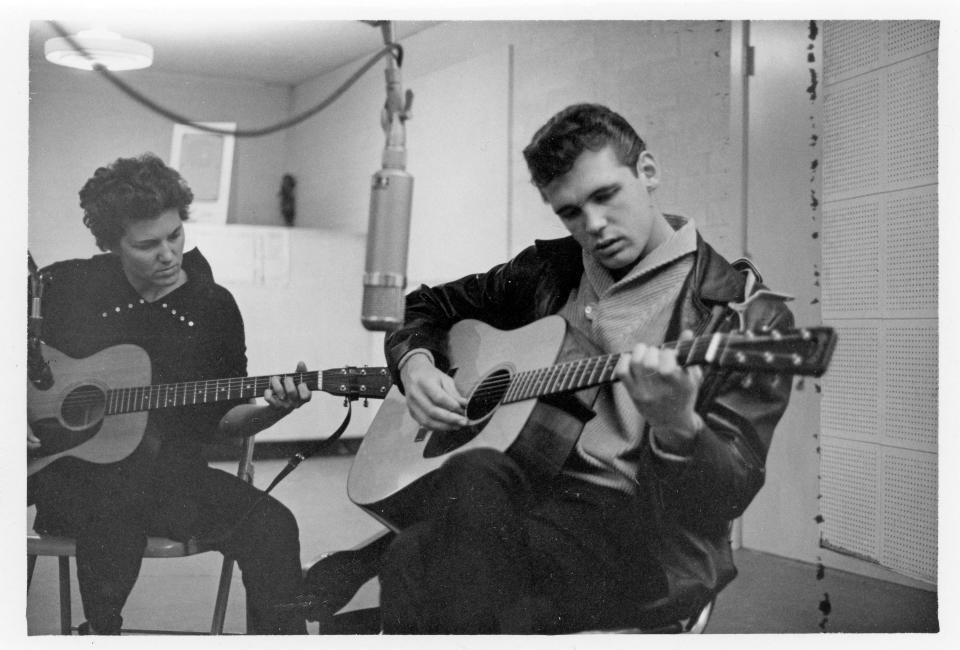

He and Delbridge formed a country duo, Jimmy & Duane. Eddy sang and played guitar while Delbridge harmonized and played piano. (At first, he played guitar.)

"We did old bluegrass things," Eddy recalls. "'Truck Drivin' Man' — by Terry Fell, I think. Wilburn Brothers. Delmore Brothers. Anything two guys could sing together. That was before we ever heard the Everlys."

It wasn't long before the two had come to Hazlewood's attention while playing around what Eddy reports was "a happening town," from high school dances to the Coolidge Armory.

The DJ liked their sound enough to book a studio in Phoenix to record them on two songs he'd written, "Soda Fountain Girl" and "I Want Some Lovin' Baby," with backing by a group called Buddy Long & the Western Melody Boys.

Hazlewood released a 45 of those two songs in 1955 on his own label, Eb X. Preston.

'America was ready for metal.' How Judas Priest delivered with 'Screaming for Vengeance'

Playing Madison Square Garden (not that one)

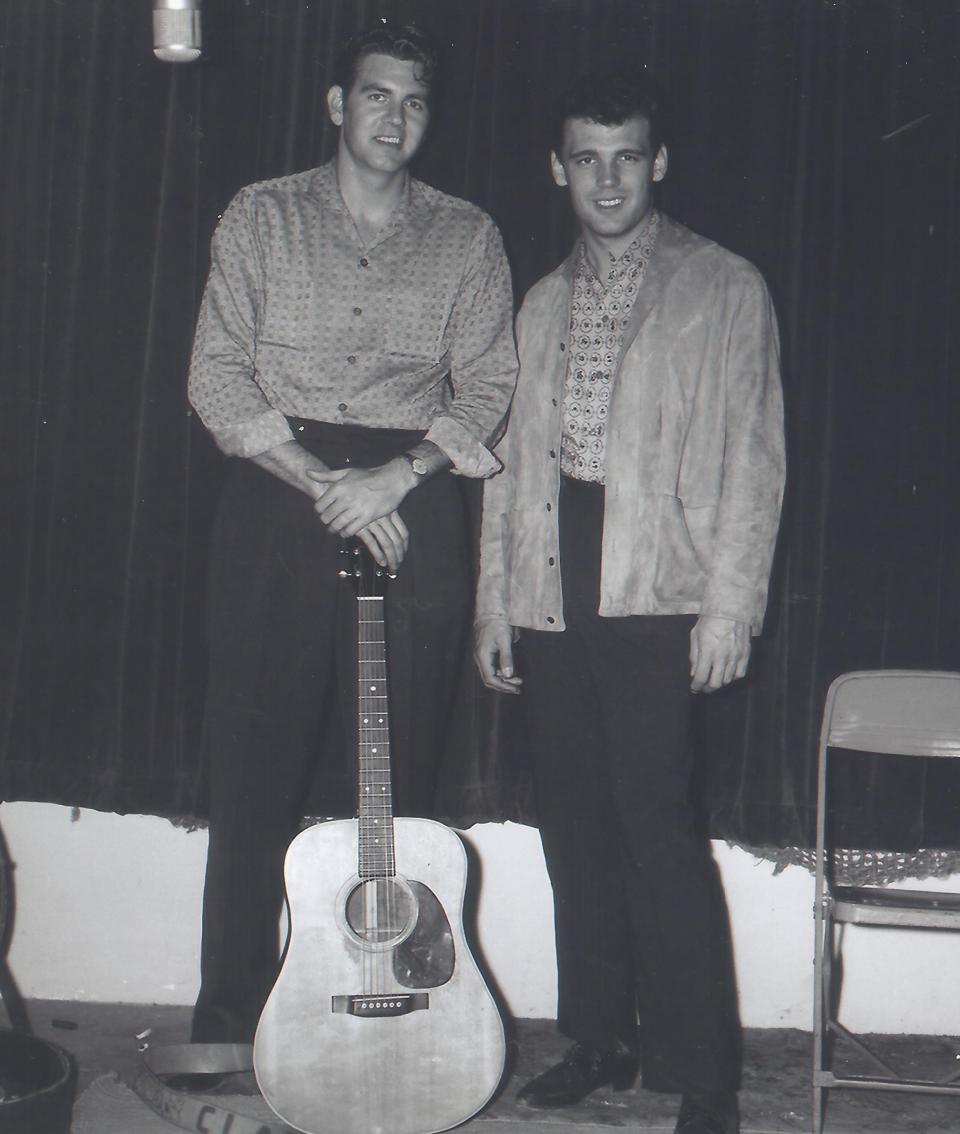

Meanwhile, Jimmy & Duane were making frequent trips to Phoenix for Ray Odom's Arizona Hayride shows at Madison Square Garden.

"I thought it was presumptuous to call it Madison Square Garden," Eddy says.

"But a bunch of desert rats, I guess they don't care. They like to be grand about things. Anyway, we'd play on the stage, which was a wrestling ring. And we had to be careful. If you stomped too hard, the reverb in our amps would crackle and go bang."

The first time they performed there, Eddy met Al Casey, who went on to play guitar on all those early Eddy records. At that point, he was a member of the Sunset Riders, the Hayride house band.

"After the first show we did, he says, 'You want to come sit in with us?'," Eddy recalls.

"He told me, 'You can play guitar and I'll play steel.' He used to alternate between them. So I did just that. I had a big time. It was great for me because it was the first real band I'd ever played with."

There was a band he'd played with back in Coolidge, Eddy says.

"But they were weekend warriors. We'd play the worst dives you could imagine. I was only 15 at the time. Or 16. I shouldn't have even been in there. But they didn't care as long as I didn't drink or wander too far from the stage."

Remembering Ray Odom: The man behind the Arizona Hayride

He said 'write an instrumental' so I did

In 1956, Hazlewood landed a hit on the national charts with Sanford Clark's "The Fool," a song he co-wrote and produced at Audio Recorders, having moved to Phoenix for a job at KRUX-AM.

By 1957, Eddy was renting a room from Hazlewood in Phoenix and had purchased his signature hollow-body Gretsch "Chet Atkins" model at Ziggie's Music when a twangy instrumental titled "Raunchy" hit the Top 5 in two versions at the same time — one by Bill Justis, the other by Ernie Freeman.

As Eddy recalls, "When 'Raunchy' hit, Lee said, 'You need to go home and write something. We need to cut an instrumental.'"

Hazlewood had recorded "everybody that could hum a tune by then," Eddy says.

"He'd take them in the studio and send the record off to different independent labels in LA to try and get a deal. I just wanted to play. And he said 'Write an instrumental' so I did."

'The most important record ever cut here.' Remembering Phoenix rockabilly legend Sanford Clark

Recording 'Rebel-'Rouser' in Phoenix

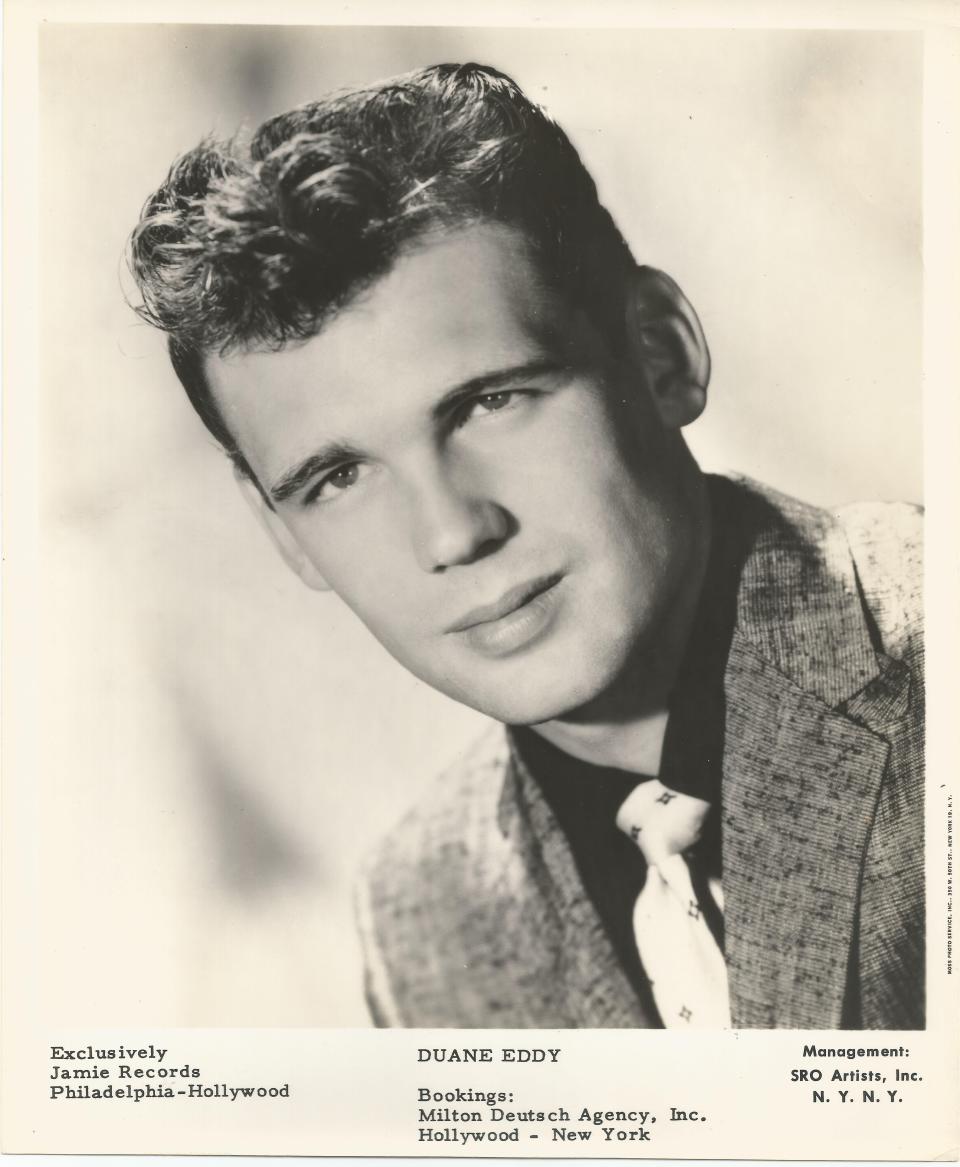

His first attempt, "Moovin' n' Groovin'," was released on Jamie Records out of Philadelphia, giving Eddy his first entry on the Billboard chart — No. 72.

"That was enough to encourage the company back east to say, 'Go do some more,'" Eddy says. "So we went in, in March of '58, and cut 'Rebel-'Rouser.' The rest is history, so to speak."

By that point, Audio Recorders had installed a makeshift echo chamber in the parking lot — a 2,000-gallon water tank they'd purchased from a junkyard, giving Hazlewood the echo he'd been missing.

He ended up adding more echo at Gold Star Studios in Hollywood while overdubbing sax by Gil Bernal and yells and handclaps by the Rivingtons of "Papa-Oom-Mow-Mow" fame (then known as the Sharps).

Bernal had played on several classic R&B hits.

"He's really a jazz player, but he could do that sleazy honkin' thing on sax because he also worked the strip clubs," Eddy says. "I'm sure he played 'The Stripper' many times."

She called herself rock's first side chick. Remembering Duane Eddy session guitarist Corki Casey O'Dell

The twang heard 'round the world

"Rebel-'Rouser" peaked at No. 6 in 1958 on Billboard's Hot 100, giving Eddy his first million seller as the first of four songs on the brilliantly titled "Have 'Twangy' Guitar, Will Travel" to go Top 40 on the U.S. charts.

The album, Eddy's first, hit No. 5, spending 82 weeks on the charts, while winning fans around the world.

By 1963, he'd gone Top 40 16 times in the States and 20 times in the U.K., where he was voted World's Number One Musical Personality in 1960 by the readers of New Musical Express.

Jon Anderson of Yes says "Rebel-'Rouser" was the first song that inspired him to buy a record.

"They’re incredible recordings," Anderson enthuses. "Very much like Ricky Nelson’s. So damn good. So clean."

'The sound of revved-up hot rods'

The best of Eddy's records have their own distinctive sound — a low-end twang he got from favoring the low strings on his hollow-body Gretsch and Hazlewood running those signature riffs through an inordinate amount of echo.

As Michael Hill wrote in an essay celebrating Eddy's 1994 induction to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, it's "the sound of revved-up hot rods, of rebels with or without a cause, an echo of the wild west on the frontier of rock & roll."

Dan Auerbach of the Black Keys is a huge fan. He had Eddy in to play guitar on four tracks on his latest solo album, "Waiting on a Song."

"You take this instrument that everybody has," he says. "You can go to a store and buy it. But nobody can pick it up and sound like that except Duane Eddy.

"That is the rarest of abilities as a musician, to take this inanimate object and give it a singular voice. His sound is so identifiable."

In 1962, the year he signed to RCA Victor, Eddy left the desert for a new life in Los Angeles.

These days, he and his wife Deed live in Franklin, Tennessee, a town he describes as a "bedroom community" 20 miles south of Nashville. They've been there nearly 40 years.

He won a Grammy for his 1986 collaboration with a British synth-pop act called Art of Noise on an experimental remake of "Peter Gunn," a song he first recorded for his second album, 1959's "Especially for You."

What was Alice Cooper like in high school? Friends and bandmates share stories

'We'd do one song a day, usually'

But the records that continue to define what people think of when they hear his name were mostly made in Phoenix at Floyd Ramsey's Audio Recorders, where they worked at a relentless pace.

"In the morning, we'd take almost 45 minutes just to get everybody awake 'cause all the musicians in Phoenix, they worked until 1 in the morning," Eddy says. "So they came in all bleary-eyed."

One musician, Jimmy Simmons, used to help them wake up by playing a really fast version of "Sweet Georgia Brown" on his upright bass.

"It was hilarious," Eddy says.

"But he was good at it. So that would wake us up. Everybody would laugh. And pretty soon, we were ready to work. We'd do one song a day usually. Later on, we got to where we could do two."

Eddy spent a lot of time at Ramsey's place on Seventh Street and Weldon Avenue, where Ramsey's father, Clay, made square dance records and released them on his Old Timer imprint.

"He had a record store in the front and used the back room to store square dance records," Eddy recalls.

"There was a barbershop in front, too. On the corner. And they didn't have a restroom. They had the studio and a glass window into the recording booth, where the tape machines were."

The Ramseys remodeled the studio after "The Fool."

"The control room became the bathroom, which both the barber shop and the studio shared," Eddy says.

"The barber shop didn't use it much. But the studio became the control room, and the storage room for all the square dance records, I don't know where all the records went but that became the studio."

'It was like a Vegas venue': How Mr. Lucky's and its joker sign became true Arizona icons

'He knew what he wanted sound-wise'

Working with Hazlewood was a great experience for Eddy.

"Because we were old friends," he says. "Since I was 15, anyway."

Things could get a little tense at times as Hazlewood worked with engineer Jack Miller to find the perfect sound.

"He knew what he wanted sound-wise," Eddy says. "So he'd sit there for hours with Jack and he would get a little frustrated sometimes because he couldn't figure out how to get what he wanted and Jack couldn't understand what he wanted either."

This was in the very early days of multitrack recording.

"So it was a new art," Eddy says. "We were all experimenting in those days."

Phil Spector taking notes in Phoenix?

Another young producer would occasionally sit in on those sessions, watching Hazlewood at work.

"Phil Spector would come over," Eddy says. "He was just a kid — 18 or 19. He'd come over and stand in the back of the control room behind Lee and Jack and listen. That's where I think he got the idea."

That idea he's referring to is Spector's legendary Wall of Sound, derived in part by musicians on multiple instruments doubling or tripling parts to create a fuller, richer tone.

"We had two basses, you know — an upright and a Fender bass," Eddy says.

"Buddy Wheeler was the first in town to have a Fender bass, as far as I know. They had just come out with them, and Buddy bought one, but he didn't get much tone. So the upright would give us the tone."

He looks back fondly on those days in Phoenix.

"That was where it all happened for me," he says. "And for Lee."

Reach the reporter at ed.masley@arizonarepublic.com or 602-444-4495. Follow him on Twitter @EdMasley.

Support local journalism. Subscribe to azcentral.com today.

This article originally appeared on Arizona Republic: Duane Eddy recalls his days as a young Rebel Rouser in Phoenix